Composites in car design: new opportunities

Composites have been discussed for decades as the future of automotive bodies, chassis and other assemblies. But what really works? We ask an expert

As we close out our March special on new materials, we cannot let the opportunity to speak with a true expert in composite materials pass us by. Nir Kahn, who spent decades working with various high-strength materials in the design of amoured cars, outlines opportunities for design using these materials. Let’s get straight to it.

Car Design News: What composite materials seem best poised for implementation in cars of the future?

Nir Kahn: In terms of mechanical properties for its weight, it is still hard to compete with carbon-fibre but of course the cost is prohibitively high for extensive mainstream use. Applied selectively though, and manufactured with appropriate cheap volume processes, it could yet break through to become a significant weight-reducer for mainstream cars.

The key will be to dilute it with cheaper and more sustainable materials, perhaps natural fibres, and concentrate it in the most structural parts of the car, rather than using it all over the A-surfaces like on expensive hypercars. It needs to be seen less as a high-tech gloss for marketing purposes and more as a practical engineering material.

CDN: What composite material seemed promising but now no longer seems feasible?

NK: There was a lot of focus a few years ago on SMC (Sheet Moulding Compound) and other pressed composite processes for A-class parts; wings, bonnets, roofs, etc, but when the component is not working hard, and the desired shape is a shiny pressed surface, painted to match the rest of the car body, they don’t really offer any discernible weight or cost advantages over aluminium or even steel.

CDN: What composite seems to be the most promising as a structural material or for assembly?

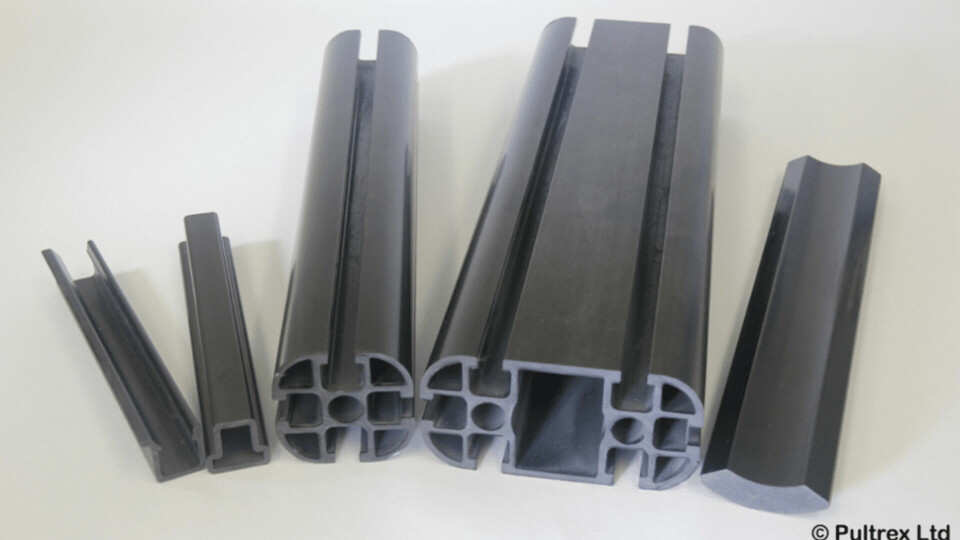

NK:I believe that even expensive structural composites like carbon-fibre can be viable in mass-production, the trick is to use cheap manufacturing processes like pultrusion rather than to assume that automotive structures must be built up from layers of pressed parts like they are in a metal body-in-white. It involves a bit of a mindset switch for body engineers, but huge weight savings can be possible without adding excessive cost.

CDN: What composite material or assembly promises to be the most impactful in terms of design?

NK: A conceptually different approach to the body architecture could open up some interesting new aesthetic possibilities as long as there is good productive dialogue between designers and engineers.

For too long we have been designing cars on the assumption that the outer surfaces are shiny and painted, because pressed steel is naturally shiny and needs to be painted.

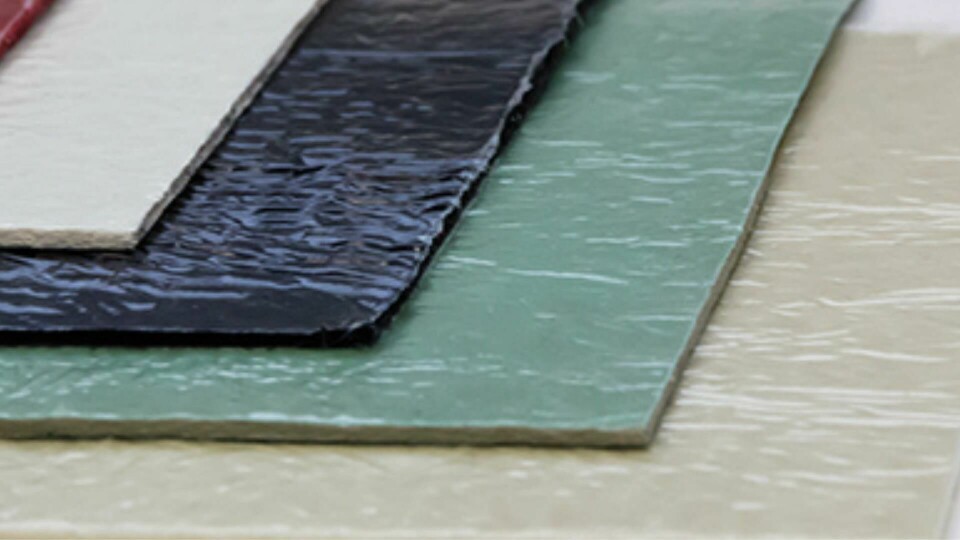

Once we break that paradigm and start from more natural material finishes – and by natural I mean how they would come out of the production process if we hadn’t explicitly designed that process to give you a smooth shiny surface texture – then we can start to explore some very new aesthetic ideas for what a car can look like.

CDN: What composite material seems most promising for automotive interiors?

NK: There is a huge opportunity for natural fibres. They don’t currently offer any real advantages for structural parts, but in interiors as a replacement for superficial plastics they can introduce a much warmer and more welcoming ambience than hard dark plastics do, and with improved sustainability too.

CDN: Any other information you’d like our readers to know?

NK: I would like to see a lot more honesty of materials in car design. There is so little authenticity in the way that we make plastics look like metals, moulded parts look like textiles, add fake lights and vents and exhausts and even windows.

In other products we would recognise the kitsch in this but somehow we get away with it even on premium cars. Lightweight composites would be viable for a lot more automotive applications if we didn’t have to add cost to meet the expected appearance of a glossy carbon-fibre weave, or imitate the look of pressed metals.

Allowing them to be natural and imperfect like we do for wood, or textured like exposed textiles, would increase their adoption and proffer a new palette for designers.

More information about Nir Kahn’s design consultancy can be found at his website here.