Design Essay: Could the Electric Revolution save the Sports Car?

Why automobile enthusiasts may not need to fear the future after all…

“The future is uncertain, and the end is always near…” Those lyrics sung by the Doors too many years ago may today be used to describe the sports car genre’s trajectory. Sales of open two-seaters in Europe and the USA, their traditional markets, have never recovered from the devastating blow of the recession: even sales of perennial favourites like Mazda’s MX-5 are still well below 2007 levels. BMW Z4 sales between 2016 and 2018 looked like a rounding error on the company’s charts, and Munich execs are on record saying the newly-launched ‘G29’ generation is going to be the last.

Poor sales of existing models discourage the development of new sports cars, expensive vehicles to design and manufacture whose enthusiastic buyers are a notoriously demanding bunch. On top of that, those enthusiasts’ definition of an ’affordable’ price is often much lower than a manufacturer’s one.

Meanwhile, as the automotive industry, almost without exception, works hard towards bringing electric vehicles into the mainstream, many hardcore automotive enthusiasts still struggle to embrace such cars regardless of their actual performance characteristics and design merit. Their argument is mostly a subjective one: they fear the “commoditisation” of the automobile into an appliance, a mere tool rather than a means of self-expression and a source of enjoyment.

Although some of the most fervent EV advocates may think this is a trivial issue, it most definitely isn’t. Many car companies have built their reputation and success around specific characteristics of their engines, creating entire legacies and loyal followings. That’s certainly not going to happen with electric motors and batteries; nobody cares who makes them and where they come from, as long as they work flawlessly.

On top of that, the production of electric motors and batteries can be heavily automated and concentrated in one place instead of across multiple sites. If that doesn’t look like commoditisation, we don’t know what does. It doesn’t stop there either: the way the driver experiences acceleration and speed won’t differ much, if at all, between comparable vehicles. Certainly not in the way one can currently tell a Ferrari from a Porsche by listening to their engines and appreciating how their transmission works. This kind of commoditisation is very likely to weed the weakest competitors out of the market for good, with only the brands whose image resonates strongly enough surviving in the new landscape. The Doors spring to mind again: “This is the end, of everything that stands, the end…” Or is it?

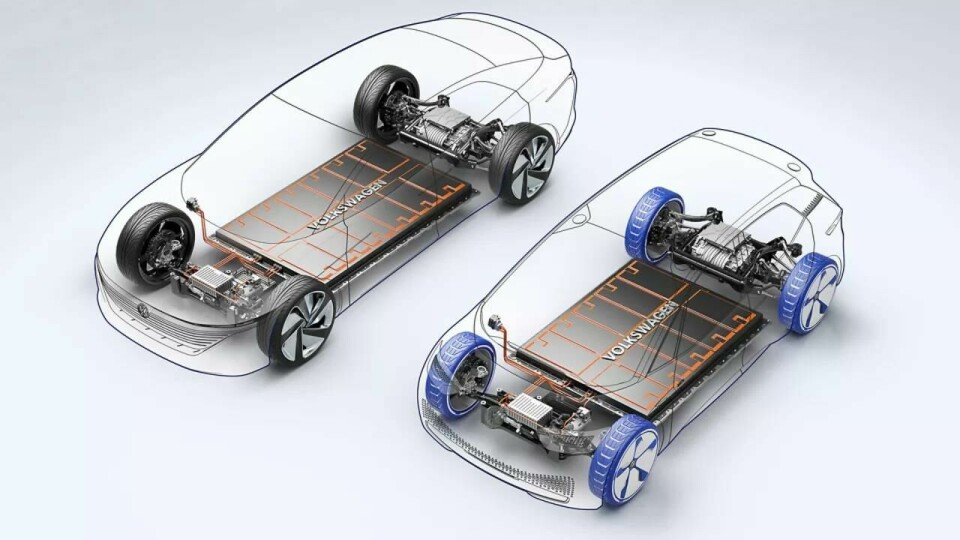

Not necessarily. Driving enjoyment won’t fade away together with internal combustion engines. Quite the opposite: the electric revolution may be the unlikely saviour of the sports car genre. If performance and what’s under the bonnet will no longer matter, it doesn’t mean the need for self-expression, indulgence, or status will go away too. The remarkable flexibility of electric vehicle architectures, with their flat battery packs and compact motors, is ideal to satisfy those desires with a diversified range based on the same core modules.

Not only is the cost of batteries bound to go down, but the cost of making the entire vehicle is bound to go down, as EVs are inherently simpler to build. According to recent research by Goldman Sachs, an electric car needs about 11,000 parts, compared to the 30,000 of an internal-combustion car. Such a reduced number of commoditised components, made in fewer factories by fewer people, could dig the industry out of the razor-thin margins hole where it’s currently stuck. That simplicity and those fatter margins are the potential saviours of the sports car, by making the business case for such niche models at the low price points enthusiasts want, easier.

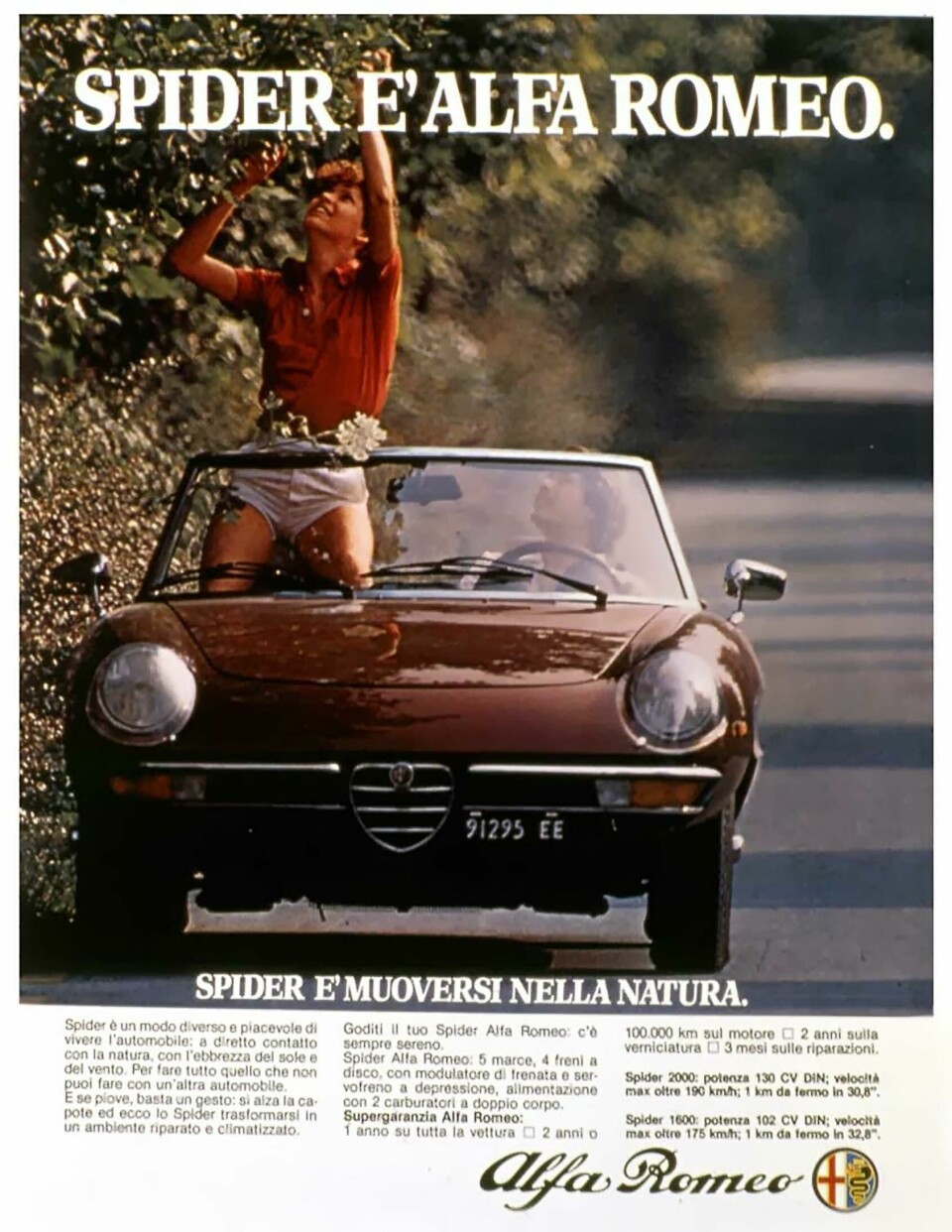

Automotive fashions come and go. We’ve seen the ‘Personal Luxury’ wave, the ‘MPV craze’ and many more besides. After the current ‘utility mania’, it’s not so far-fetched to imagine a kind of “return to playfulness.” Back in the late 1970s, Alfa Romeo advertised its Spider with a headline that captured the charm of drop-top motoring like few managed before or since: “Spider é muoversi nella natura.”

Roughly translated, it means “Spider is to travel in nature,” and that’s what a roadster is all about. Approached this way, “electric sports car” ceases to sound like a dichotomy and starts to become desirable. Drop-top motoring immerses the driver and passenger in their surroundings. They will move through nature without disturbing it, almost like a cyclist, but with the quick, seamless acceleration of the electric motor available at a blip on the throttle. The concept of moving fast, immersed in nature with only the wind to listen to, may lead the future sports car designer to adapt the design language from outdoor sports equipment such as mountain bikes.

Things like the need to explore, experience, and seek thrills are part of human nature, and the EV revolution may yet be the ticket for a new generation to enjoy driving again.