The key trends influencing automotive lighting design

What are the main trends shaping lighting design, and why has it become central to contemporary products?

Has lighting become the hottest ticket in automotive design? It can’t be far off. Each new launch seems to lean increasingly heavily on lighting to separate models and brands from one another, not only outside but inside the cabin too.

Technological breakthroughs have elevated lighting’s position as a tool for design and brand identification. Or in plain parlance: it’s all about creating fancy light signatures. However, this may be a little reductive, as lamps are now being employed not only to illuminate but also to communicate in new ways. Not just turn signals, but displaying the driver’s (or car’s) intentions while driving. It can also be used as a tool for entertainment, perhaps creating goalposts on a wall or laying out a grid for children to play hop-scotch. The opportunities, it seems, are boundless.

Based in Paris, Paul-Henri Matha is the CEO of Driving Vision News but before that spent a fair stint in the industry as a lighting expert both across broader organisations but also embedded directly with OEMs like Volvo Cars, Renault Groupe and the Renault-Nissan-Mitsubishi Alliance. He has seen plenty change during his time as a self-professed “lighting design addict” and, for our May focus on lighting, gave CDN a top-line overview of what’s happening in this space.

Car Design News: What are the key issues dictating how lighting designers work?

Paul-Henri Matha: I see three main issues. Regulation that define lamp position – including height, width and the distance between lamps. The second relates to the vehicle platform; when vehicle designers start sketches and 3D modelling, the wheels, hood and windshield already have a fixed position. As a designer you always want short overhangs, so you will not be able to fit your lamp where you want, but where you can. This is the big mistake between engineers and designers. The lamp is like an iceberg: the hidden part is big. The smaller the lamp aperture is, the bigger the hidden part is.

The third issue is performance. For the best performance, you need the biggest volume. You can think of it almost like a physique, or comparing a four-cylinder engine against a V12. The main problem is that when you design premium lamps, you want a nice slim lamp. This can be complex to achieve.

CDN: Has lighting always been seen as an element of ‘design’? Did it sit in a different department before?

PHM: Automotive lamps started to become a design element in the 2000s. Before that, it was mainly a standard component – e.g. a round or rectangular shape – and you could just design around it. Sometimes there was a really nice design, like a pop-up lamp, but the lamp itself had no design.

In the 2000s, crystal plastic lenses came on to the market and replaced glass lenses. This means all type of shapes became possible. It was also possible to see inside the lamp, and hence the lamp component design role was created. In the 2010s, halogen bulbs were replaced by LEDs, then came the big 180mm diameter round reflectors, which can become a 20mm tall slim module. This dramatically changed lamp design and exterior vehicle design.

If we talk about the lamp engineering department, historically those teams have been part of the exterior team alongside the body team with bumpers, exterior trim etc. That has not really changed now as they are still part of vehicle exterior teams, but they do have more of a connection with the electrical and software teams.

CDN: What are a few significant changes to lighting design you have seen over the last few years. Did a new technology suddenly revolutionise things?

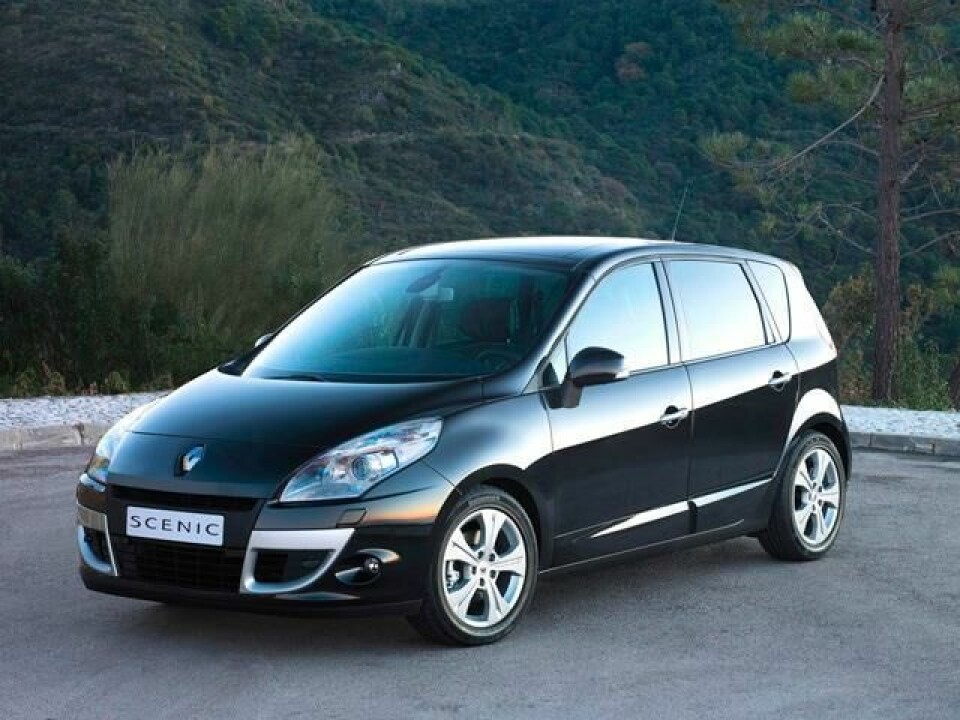

PHM: The shape of the lamp would be the first significant change, in my opinion. In 2006 I developed this Renault Scenic lamp with Francois Leboine during our time at Renault (below). This one one of the biggest lamps in the world; it was not easy to injection mould and required a huge machine, 1500 tons if I remember correctly.

Nowadays we see lamps that are two, three or four times as big. You need to take into account a huge number of constraints, from thermal dilatation, manufacturing, transportation, aftermarket requirements and so on. It is not easy to find the correct stakeholder that is able to manufacture it, but two-metre long lamps like the Lucid Gravity or Renault 4 are becoming quite common nowadays. Changan has a 2700-ton injection machine for its outerlens production, for example.

I also see a growing importance of perceived quality and the homogeneity of the signaling function. Everybody is looking at all of the details today, and you need to design the perfect beauty. Ten years ago, designers were more focused on the shape only, less on the lit aspect. That has totally changed.

Another major change I have seen is the importance of UX for exterior and interior lighting, including display integration. Ten years ago exterior designers did not care at all about the welcome sequence, the possible interactions with customers or other road users. They were doing 2D sketches and 3D models only. Today it is a bit different, even if this UX task is more often done by another team in the studio.

CDN: At a broad level, we are seeing increasingly homogenous car exteriors, particularly with EVs. Is there a prevailing trend in lighting design – horizontal light bars, perhaps?

PHM: When I was a kid, and later a young lighting engineer, I was able to recognise each vehicle by night. Today, this is difficult. Most of the new EV makers have this horizontal light bar, but you can see differences in the thickness. For example, a 100mm thick bar on a Rivian versus a 10mm bar on a Li Auto. This is challenging for designers to keep a certain DNA and avoid copying competitors – you need to maintain a certain level of creativity. At the same time, proportions are becoming similar, not only lamps which means that most of the time it is only exterior lighting that can distinguish some cars. This is the beauty of our job, and ‘fade design’ can become really cool as dusk draws in.

I’m convinced lamp design and integration will evolve, from vintage designs with round shapes (Ineos Grenadier) to pop-up lamps (Volvo EX90)… Everybody is thinking now, and when you think, you become creative

CDN: Safety and functionality were the original purposes for exterior lighting on vehicles. Is this still true today? Has the hierarchy between “looks” and “function” evolved?

PHM: In the 2000s, if you were rich or wanted to have good lamp performance, you bought a car with xenon lamps, an option that cost you more than €1,000 probably. You multiply the light flux by three; you were the king.

With bulbs replaced by LEDs, today a Renault Clio or VW Polo can achieve the same flux as a Mercedes S-class with xenon lamps from the 2000s. Performance has been replaced by advanced lighting systems, like ADB. Here, you drive in high beam all of the time but your camera detects oncoming cars and removes light from where the oncoming car is. This is possible due to new technologies like Pixel lamps and HD lamps.

These advanced lighting functions are still important in Europe and especially Germany with a high take rate on premium cars. However, it has never been an important topic in North America (due to legal constraints) and it is not the main topic in China. This is especially due to the fact that people are driving most of the time in cities. If they have advanced lighting systems, they use it for a welcome function, gaming or camping. For example, the Aito M9 has a take rate above 70% for HD lamps.

This is clearly a shift from performance to function. Young drivers are far more focussed on function versus safety and performance. In China they have forgotten the performance, in Europe they try to combine both. In India, they focus on performance – potholes are a big topic. As a designer and engineer you have to take into account all these constraints, especially if you develop for different markets. If you are more focussed on China only or Europe only, it may be easier.

CDN: Is lighting design in a good place right now – do you like what you are seeing?

PHM: I am a lighting and design addict, so I will say yes. However, everybody is starting to have some doubts. OEMs spent a lot of money on lamps over the last 20 years and the budget for lamps increased five times over. Complexity also increased, as has the price of aftermarket lamps. People are thinking: is it all too much? Should we reduce complexity? Should we switch from a technology perspective to a more sustainable (or reasonable) perspective with something that is simpler to repair?

Lamp makers are the hidden people, they work like hell

We see this trend in the vehicle industry and also lamp industry, especially in Europe with brands like Citroen, Dacia and others. Meanwhile, Toyota has used replaceable light sources from more than ten years now. You can replace lenses on a lot of Toyotas in Japan too.

Will lamp design and lamp integration change? Yes I am convinced of that. What will be the new lamp design? For sure we will see different evolutions, from vintage designs with round shape (Ineos Grenadier) to pop-up lamps (Volvo EX90)… This is becoming very interesting because everybody is thinking now. When you think, you (re)become creative.

CDN: How much of lighting design is led by in-house OEM design teams, and how much by Tier 1 suppliers? Do suppliers get the credit they deserve?

PHM: There is no common practice. As an example, a lighting design studio is typically anywhere from 1-10 designers; OEM lighting R&D teams are usually 50-100 people; and big lighting Tier 1s have more than 500 lighting engineers.

OEM designers do the 3D A-class modelling. Technical concepts are usually done by OEM R&D teams, and lighting set makers (the Tier 1s) are doing the detailed lamp design, which generally takes the most time. Lamp makers are the hidden people, they work like hell to keep the schedule. They are not really well known, but at DVN we deliver every year an award for the best lamp to a Tier 1 to recognise their effort.