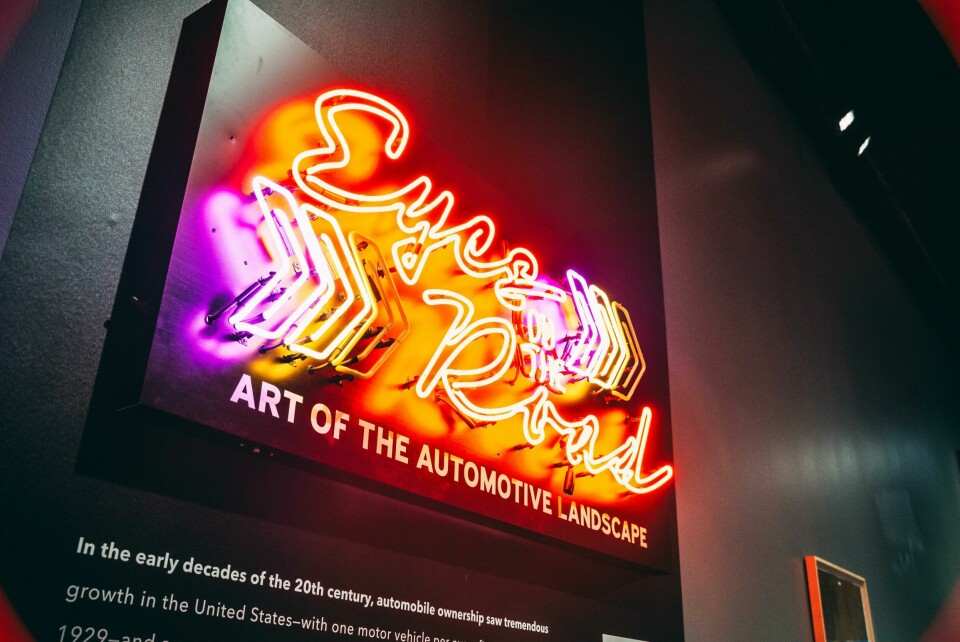

Review: “Eyes on the Road” at the Petersen Museum

The Petersen’s new exhibit examines the artwork inspired by automotive culture

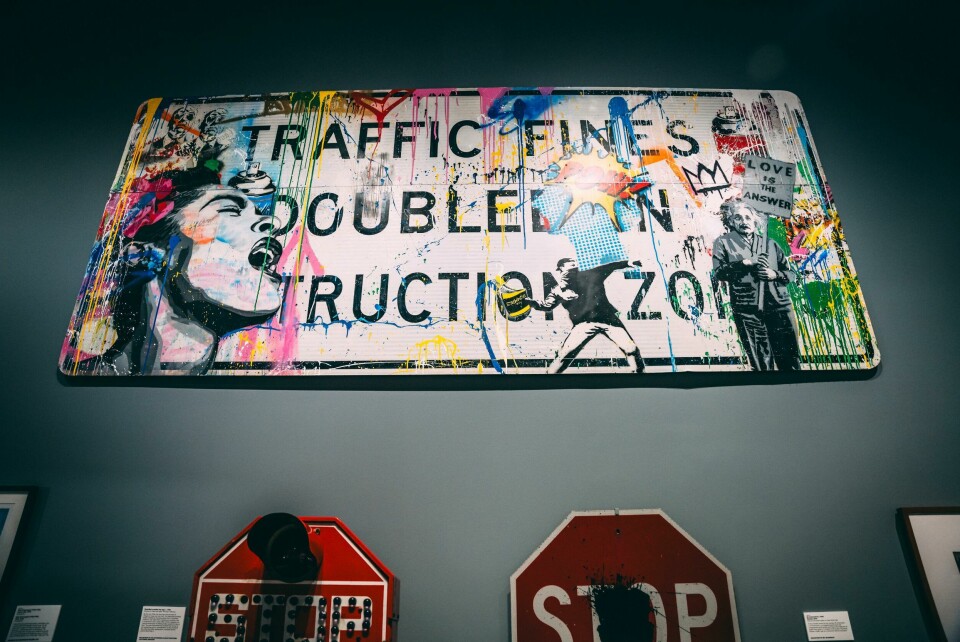

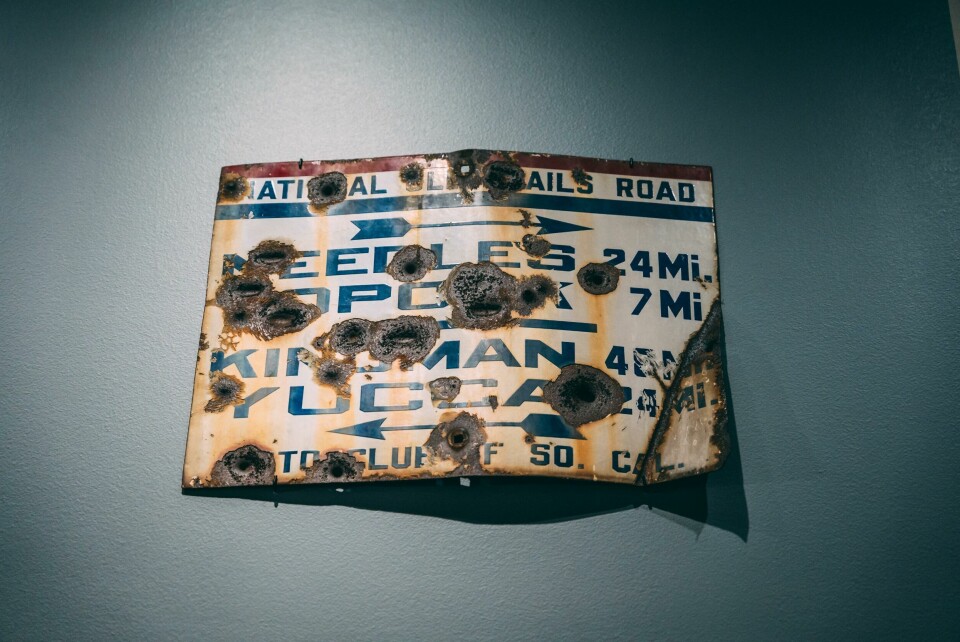

Opening this past weekend, the Petersen Automotive Museum’s latest exhibit ‘Eyes on the Road’ features artwork inspired by cars and automotive culture. There are no fabulous portraits of cars, racing drivers or famous races here, however. The art on display focuses on the everyday objects and places that serve the automobile and, whether intentionally or accidentally, rise to the level of an art in themselves.

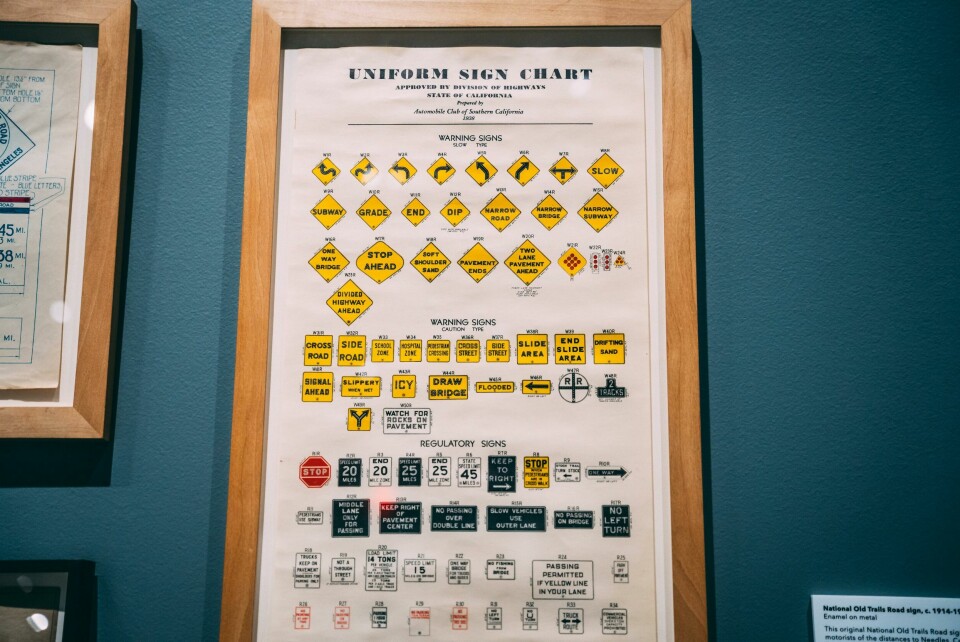

No exhibit of this type would be complete without Ed Ruscha’s work. The artist, who has worked in Los Angeles since the 1960s, and whose work which celebrates the banal and everyday, is prominently featured in the exhibit. And for good reason: He has chronicled and commented on, through art, film, books and photography, the automotive landscape of Los Angeles for over fifty years. His iconic artwork “Standard” is on display, but also his signage and typography, which recalls the typography of road signs developed for the region (some of which are also on display).

Also featured are the works of Harry B. Chandler, which recall the style of Wayne Thiebaud (sadly absent here). Two large paintings, which illustrate aerial views of freeway intersections in seemingly bucolic landscapes, are an interesting comment on the freeway invading nature- until you realize that “nature” is often a curated landscape – subdivided, planted with non-native crops and cultivated by machines. The freeway just adds one more man-made element to the landscape.

This being the Petersen, there are of course cars on display. Three are essays on the tail fin, and the fourth is the magnificent Dymaxion Prototype Number 2, the interior of which was restored by Norman Foster as part of the construction of his own replica of the Dymaxion car (the exterior is now renewed as well).

The tailfin cars are the Chrysler Ghia “Gilda”, which is basically two tailfins on wheels, the GM Astro II from the late 1960s, and the comical Astra-Gnome from the 1950s – a heavily modified Nash Metropolitan minicar. All are restored and provide an interesting glimpse into “yesterday’s tomorrows”, into the era when jet fighters and rockets were predicted to heavily influence car design and propulsion.

If there is any fault with the exhibit, it is that there is not enough of it

If there is any fault with the exhibit, it is that there is not enough of it. Located in the smaller Armand Hammer Gallery, the collection cries out for ‘more’. There needs to be more artwork from Ruscha, Warhol and other artists such as Wayne Thiebaud and James Rosenquist. Some more cars would help, too, though there was no additional room in the gallery. You had to tour the whole museum (and the Vault) to get a sense of the art of the automobile, and the visual culture it inspired.

Additionally, there was no part of the exhibition dedicated to the peculiar and wonderful strain of Modern architecture called “Googie” Modern, a commercial Modernism that had its roots in Los Angeles, and celebrated the car and the kinetic automotive motion of the Strip (Sunset, Wilshire, and otherwise). The style was incredibly inclusive, with oddball combinations of glass, stone, steel, plastics and ceramic tiles all assembled in off-kilter combinations that were nevertheless very functional, and celebrated the movement of the automobile in the city.

Interestingly, in the next gallery was the long-running Tesla exhibit, which sadly, only overlapped “Eyes on the Road” by a couple of days. But Tesla and Space X, SolarCity (now Tesla Energy), Hyperloop, and other Musk companies, really embody the futuristic spirit that once infused America and created the very work that inspired the artwork in “Eyes on the Road”. Tesla is also embodying the “Googie” spirit by creating a coffee shop/charging center in Hollywood.

It will be interesting to see if Tesla and Elon Musk can generate the kind of artistic expression that reacted to the culture of internal combustion that ruled before the oil crises of the 1970s. Or has culture (and the automobile) moved on?

Whatever the answer, outside the museum, the thrum of heavy traffic on a Friday afternoon gave witness to the endurance of the automobile in everyday Los Angeles culture. Except there is ten times the traffic in LA now as there was in the Reyner Banham/ Ed Ruscha days and the strained infrastructure is constantly being torn up, repaired, replaced, and torn up again. Navigating all this construction is an artform in itself. Call it the real “Eyes on the Road”. Hopefully, a more artistic future of automobility awaits.