BAC explored generative design for its new Mono

Co-founder and design director Ian Briggs gives us a glimpse at the near future of car design

Few will be as disappointed at the late cancellation of the Geneva Motor Show as the people at BAC, who had a prime spot for their show stand right next to the likes of Maserati, Ferrari and McLaren, in the hopes of catching a few European supercar buyers’ eyes with their newly evolved single seater. However, undeterred, they’ve replicated their show stand within their recently built Innovation Centre at the company’s base in south Liverpool – or ‘Geneverpool’ as they nicknamed it for last week. CDN paid them a visit.

The star of their detached two-tier show stand was the new, second-generation Mono, featuring the company’s first use of a turbocharged engine. Most of the exterior design updates over the original car were first seen on the limited-run Mono R we covered last year – article here – but now that it has an EU6D-compliant engine, the rest of the car has been homologated for sale in mainland Europe too. This has led to a fresh round of detail changes compared to the R, as design director Ian Briggs explained to us.

“Obviously we have to use E-marked lights. The rear lights are slightly bigger, so there was quite a bit of design work around that area around the rear wing to fit them in,” he began. One more noticeable difference at the tail is a pair of vertical red reflectors. “The cool place to put them would’ve been on the underside [of the diffuser] but it was just too low – we don’t want a really high-downforce car, we want a nice driveable car with a progressive breakaway – and to get it high enough we would’ve had to place an extra element in here and it just started to get cluttered and lost its clean look.” The trailing edge of each inner rear wheel arch now tucks in, because as Briggs explained, “you’ve got to see at least 50% of it from certain vision angles, and this cut means that [from a rear ¾ angle] can see at least 50% there [on the other side].”

In addition, a new exhaust silencer led the design team to further elongate the tailpipe housing and the rear crashbox beyond the rear wing, also emphasising the super-narrow central structure of the car.

Working forwards, there are new, single-piece 3D printed mirror stalks (now with an aerofoil profile) carrying new, larger mirrors further outboard. This particular adjustment for EU homologation came with surprising visual benefits, to do with visual scale. “Ironically, having done this kind of thinking ‘ugh I have to make the mirrors bigger’ I actually feel the bigger mirrors make the car look smaller,” commented Briggs. “Also, adding a bit of body-colour makes them look less like an afterthought as well – now I feel like it’s incorporated nicely into the design, with the aerofoil and the blade and the fact that this surface ‘floats’ above [the main body], you’ve got all those different elements that we see in the rest of the car.”

Between the mirrors, the carbonfibre steering wheel now has a pronounced ridge along the back of the lower edge as well as the top, to improve ergonomics during tight manoeuvring.

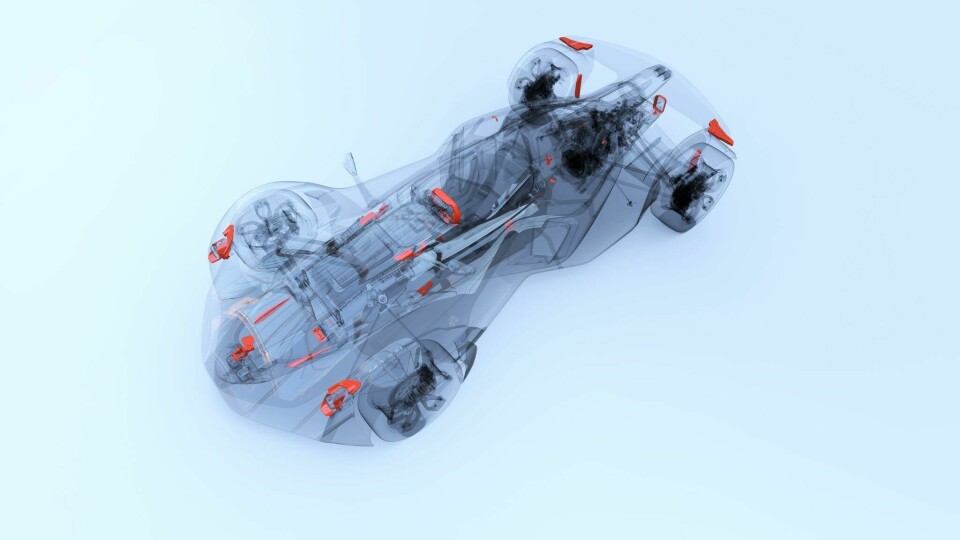

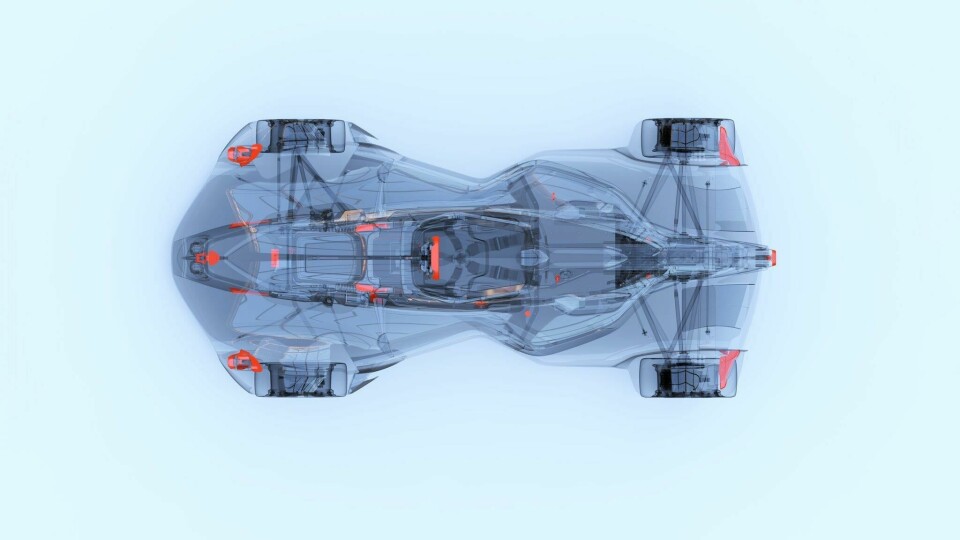

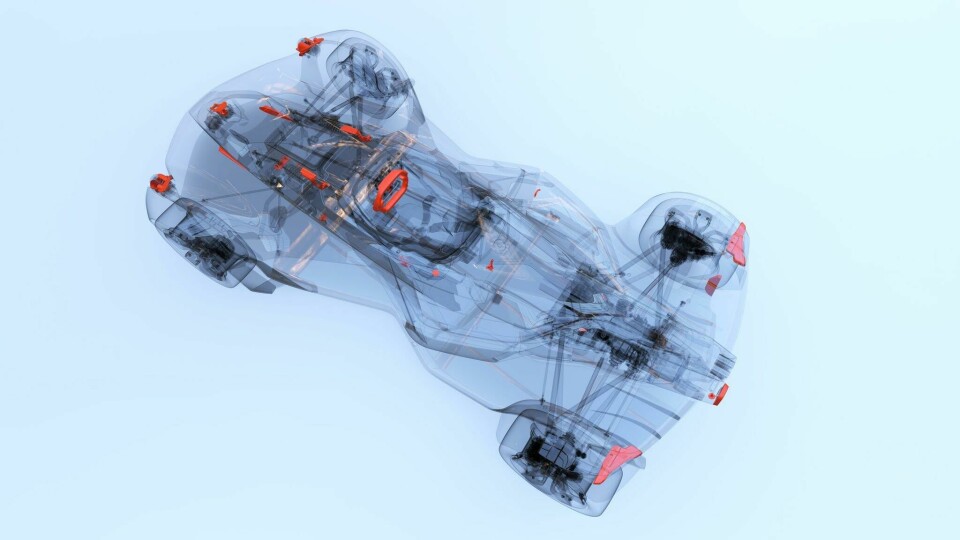

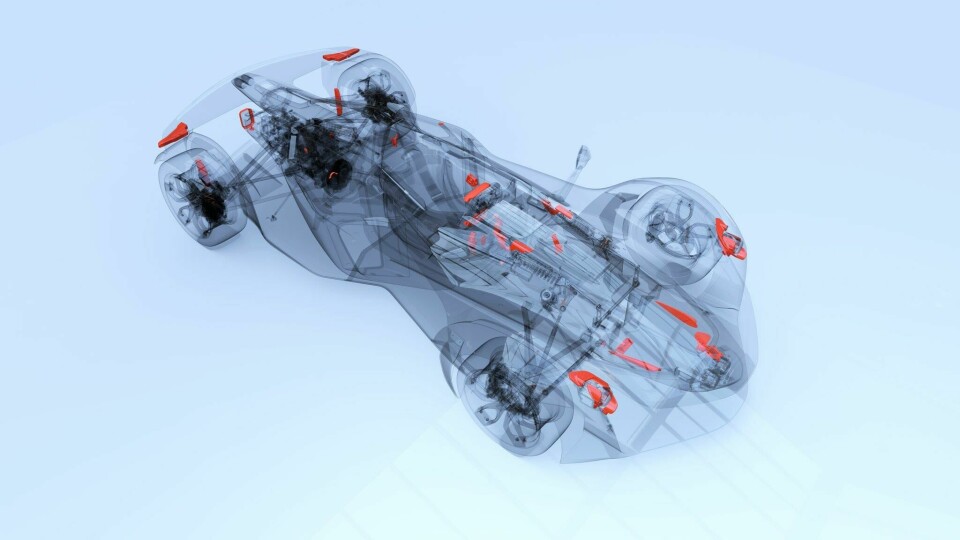

– All the red-highlighted components in these ’X-Ray’ images are 3D printed

The LED headlights have also been tweaked and are housed within a set of 3D printed components. In fact, there are over forty 3D-printed components on the new Mono, and additive manufacturing is very much a technology that BAC wants to use more and more as the costs involved keep coming down (the same is true of graphene, currently used to reinforce and lighten the bodywork) – but that’s just half the story. So, rather than go further into that, we shall instead dive into the mysterious realm of ‘generative design’, by looking at the new Mono’s wheels.

While the 17-inch carbonfibre rim is unchanged, the metal centrepiece which bonds and bolts to it has been lightened and improved through a collaborative project with Autodesk, using their Fusion 360 software. For reference, the centrepiece seen on a 2019 Mono R wheel weighs 3.4kg and was three-axis machined. Briggs said that at the start of this project, “we weren’t really aware of where we could remove material, and in the past, you’ve got what’s called ‘finite element analysis’ – you’d put the forces on it, you’d see the red areas and the green areas, you’d take some material away in the green and you’d add some in the red – you’d basically go ‘manually’ through the process, reiterating until you ended up with something that you’d optimised. Well, what generative design does is it just does that itself and in four hours you’ve got like 100 solutions if you want! And it can go as far as you like.”

However, generative design isn’t quite the perfect solution, and creating theoretically ideal shapes using simulations based only on the material used often led to extremely elaborate results that milling machines couldn’t create. With input from BAC, Autodesk developed Fusion 360 to also account for the selected production method.

“Generative design tended to make things that look like trees, so that was maybe something that was only 3D printable,” explained Briggs. “Well, as long as that’s too expensive, then that isn’t really a helpful solution. But what you can do with it now is you can tell it ‘only give me solutions I can machine in three-axis’, or ‘only give me solutions I can machine in five-axis’, because Autodesk writes the software that runs the milling machines, so the algorithm can constantly be checking with that software about what it’s capable of doing and what it can’t.” The end result – now five-axis machined – is a version of the five-double-spoke design that not only weighs 1.22kg less, but no longer has any stress concentrations, meaning that the force from any heavy impacts with a kerb are sent evenly through the whole wheel. Once married to the carbon rim, a finished 2020-spec Mono wheel only weighs around 4.7kg.

“It’s looked at all the different areas where we could remove material and it took a lot of material out of here [see the cavities next to the bolt holes], which wouldn’t have been accessible unless the head of the miller could come in to the different angles,” Briggs elaborated. “It’s taken an awful lot of material out of the side [of the spokes] as well.”

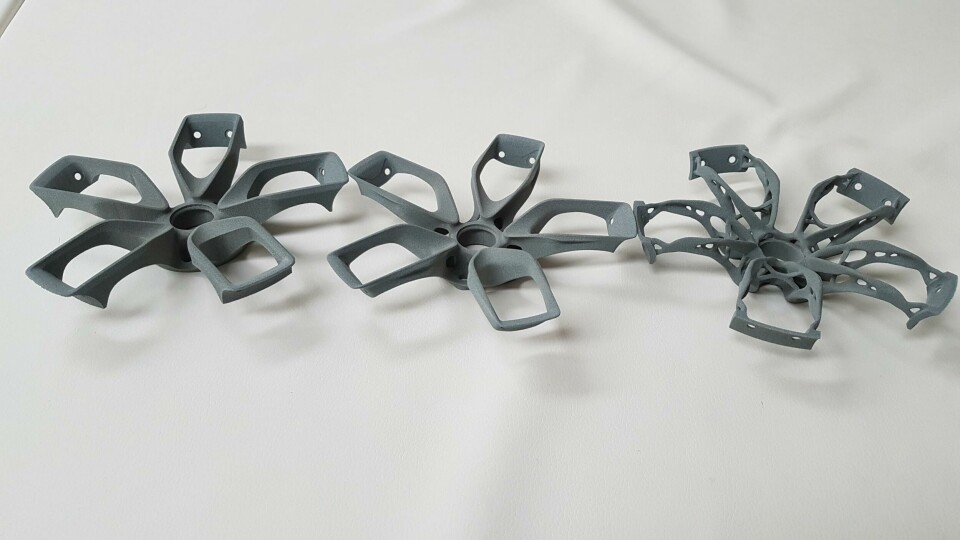

The latter change creates a spoke design that almost appears to be sucking its cheeks in, making itself as thin as possible – which befits the rest of the car’s appearance. However, even once it’s accounting for production methods, the system still spits out some bizarre, random-looking forms – as demonstrated on a scale model of a purely generative wheel design, plus an AP Racing brake calliper and suspension upright that we were also shown from BAC’s experiments.

“These are some of the slightly odd-looking shapes you end up getting, things you just wouldn’t do as a designer – wide-thin-narrow-sharp-rounded – which… maybe our eye just has to get used to it,” commented Briggs. “It’s less shocking to me now than it was. There was a time when it was like ‘that’s just ugly!’. But now I’m starting to find it cool because see, look how thin it gets in places!”

We can certainly think of examples where initially shocking car designs and aesthetics were later accepted as people acclimatised, so perhaps this will prove the case with wild, intricate, algorithmically generated designs. But in the meantime, Briggs hopes to work with Autodesk to find a happy medium. “The next thing that we’re looking at doing with Autodesk, as we help to develop the product, is they want to understand ‘what does a designer want to do to that?’ and then, can we almost do something like in a rendering program, where you have sliders for how radiuses transition, how cross-sections change. Can we make it so the designer can have some influence in the algorithm in the same way that manufacturing guys can, so that the final result is closer and closer to what you really want?”

The idea then, for the time being, is to find forms with the right structural characteristics that don’t look ‘too weird’ like the twisting beam along the top of that brake calliper. But given the steadily falling costs of 3D printing and the growing familiarity with this new, unnatural yet organic form language, we could well see automotive design heading away from the form languages we currently know anyway.

“Y’know, the next step is probably to go such that it looks more organic, more generative, and I think then we wouldn’t limit it to a 5-spoke wheel, but I think the aesthetic of the rest of the car has to match that. The next step, which you saw on [the 3D printed scale model], the rest of the car somehow has to fit that and you’d want generative-design wing mirrors, steering wheel, suspension – it would all have to speak that language I think, otherwise it would just look a bit odd. You’ll see on the calliper they haven’t paid any attention at all to the aesthetic, and it has a sort of beauty in that as well…” noted Briggs, adding “I’m excited to see where generative design will take us.”

So then, while the Mono we see here will continue to evolve iteratively for the time being, could the Mono of 2035 or 2040 look more like a composite-and-graphene plant has grown from printer-powder soil? We will have to wait and see…

– Gallery: the 2020 BAC Mono