Cars and the City: a study of the Salone

With countless international designers and exhibits, the automotive world has long felt the attraction of Milan’s design festival Salone del Mobile. Jonathan Bell examines the origins of the relationship and why it continues to grow

The very first Milan Furniture Fair, the Salone Internazionale del Mobile di Milano, was held in 1961 to aggregate the wares of the region’s many furniture manufacturers. Milan had been home to industrial exhibitions since the 1920s, and the first Salone followed on from these Fiera Campionaria, themselves evolved from Milan’s Great Expositions of 1881 and 1906. By the 1920s, the country was a globally recognised nexus of industrial production and contemporary design.

The new Salone del Mobile capitalised on this image and over the decades became the primary outlet for the latest innovation in contemporary design. As it grew, the show embraced more and more international companies, as well as sectors like interior design, lighting, home automation, textiles, material technologies and many more. For the creative industries, it became the ultimate annual one-stop-shop of inspiration and innovation, a place to gauge the temperature of global taste and incoming trends.

Since 2005, Salone has been held at the new Fiera Milano site, designed by Studio Fuksas, and featuring nearly 400,000 square metres of exhibition space.

Car design was siloed into its dynamic and heroic category, but even the most prosaic brand saw no value in any association with the furniture industry

In the 21st century, the auto industry has forged strong new ties to Salone. Milan’s exhibition spaces have a long historical association with the motor industry; the city hosted Italy’s second motor show, the “International Motoring and Cycling Exhibition,” in May 1901, and an auto show was part of the inaugural Milan Fair in 1920.

Yet by the time Salone proper was underway in the 1960s, the main focus for car makers and designers – in particular the dense creative network of coachbuilding studios that had its nucleus in Turin – were the prime era international motor shows.

In the 60s, ‘design’ simply wasn’t understood, discussed or considered in the same way as it is today. Car design was siloed into its dynamic and heroic category, but even the most prosaic brand saw no value in any association with the furniture industry. With the emergence of a new, premium consumer culture that valued ‘design’ in and of itself, the automotive industry realised it could simultaneously conflate its own values with those of brands and names from other disciplines. A mutually beneficial circle of recognition was created.

An early adopter of Salone culture was Lexus, which started a series of ‘L-finesse’ exhibition there in 2005, a collaboration with the architect Junya Ishigami (designer of the 2019 Serpentine Pavilion in Hyde Park), the painter Hiroshi Senju and architect Kazuyo Sejima

Salone del Mobile provided the perfect platform for these collaborations to flourish. From 1998 onwards, the fair itself had fragmented, spilling out across the city’s various districts via the SaloneSatellite offshoot, with a focus on emerging designers, new companies, installations and events. It was ideal for large multinationals armed with substantial marketing budgets in order to embrace and engage with a global creative audience.

Car brands began to build their presence at the show. An early adopter of Salone culture was Lexus, which started a series of ‘L-finesse’ exhibition there in 2005, a collaboration with the architect Junya Ishigami (designer of the 2019 Serpentine Pavilion in Hyde Park), the painter Hiroshi Senju and architect Kazuyo Sejima. The following year, Lexus exhibited a fibre-optic enhanced model of the LS 460 at the city’s Museo della Permanente during the 2006 Salone, created with designer Tokujin Yoshioka. 2007 saw Kumiko Inui and Norimichi Hirakawa’s ‘Invisible Garden’ installation, this time using an LS 600H, while the company teamed up with Nendo in 2008 for the ‘Elastic Diamond’ installation. The final L-finesse presentation was in 2009, when architect Sou Fujimoto (another eventual Serpentine Pavilion alumni) designed the ‘Crystallized Wind’ installation.

The Audi City Lab was another initiative driven by Salone’s confluence of art, design and architecture. Working hand in hand with a number of high-profile designers, the City Lab started out as a concept store on Via Montenapoleone, a place for presentations and discussions. This included showcasing the other brands in what was then designated as VW Group’s ‘Audi Group’, including Audi, Ducati, Lamborghini and Italdesign Giugiaro. It was also an expansion of the Audi Urban Futures Award, a globe-trotting event that started in Venice in 2010 in order to reward architectural responses to urban mobility.

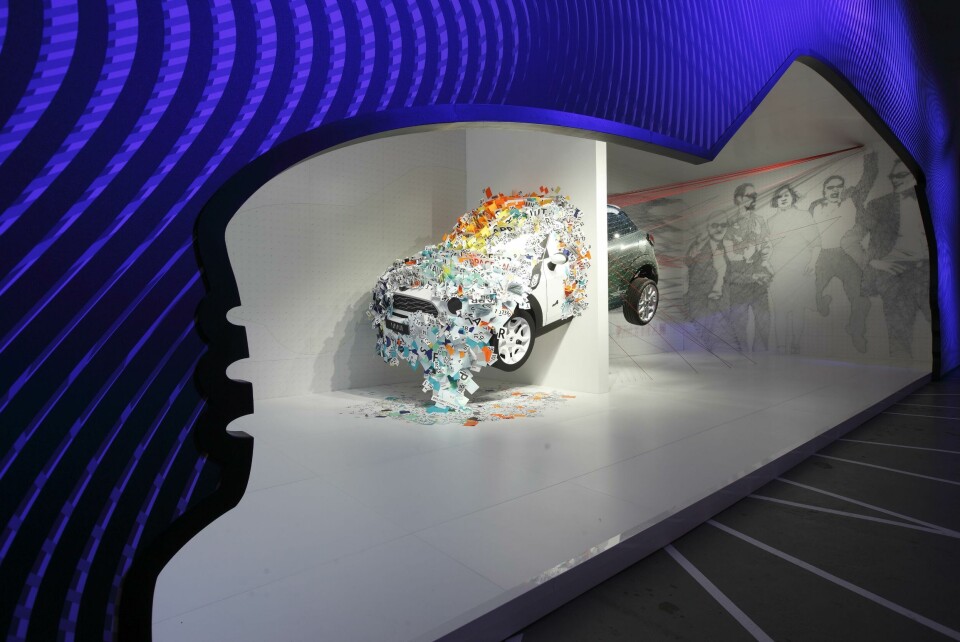

Other Salone pioneers include MINI, which teamed up with Danish furniture company Fritz Hansen in 2009 to present a MINI Cooper S Clubman along with a bespoke Airstream trailer, complete with an interior including the Egg and Swan chairs by modernist icon Arne Jacobsen

Over the next few years, the Milan-focused City Lab evolved from a showroom into a series of installations around the city, including MAD Architects’ ‘Fifth Ring’ in the courtyard of the Seminario Arcivescovile in 2018, and ‘Enlightening the Future,’ a light piece and interior concept shaped by Dutch designer Marcel Wanders in 2021. The latter included an RS e-tron GT and the A6 e-tron Concept, set alongside a lounge stuffed with design classics as a place for pause and reflection.

For Lexus, the ancillary activity around Salone allowed the company to focus explicitly on the car as a pure form, exploiting the show’s gallery-like ambience and more ascetically-minded audience to highlight subtleties that couldn’t be conveyed in the frenzied fug of a motor show.

Following a four-year hiatus, Lexus returned to Milan in 2013 with a new initiative, the Lexus Design Award. Announced in October 2012, the themed award scheme quickly attracted over 1,000 entrants from around the world, with a shortlist going forward for mentoring with the judging panel to develop their future-facing designs across a broad range of disciplines. Lexus described the LDA as an ‘initiative […] to nurture creativity and support the skills and vision of young designers working around the world.’ Over a decade, the LDA has become a Salone staple, a generation-crossing event that has brought a youthful lustre to a brand that was arguably born into middle age.

Other Salone pioneers include MINI, which teamed up with Danish furniture company Fritz Hansen in 2009 to present a MINI Cooper S Clubman along with a bespoke Airstream trailer, complete with an interior including the Egg and Swan chairs by modernist icon Arne Jacobsen. The first of what were to become known as the ‘MINI LIVING’ installations, the pairing was billed as a surfer’s dream modern transport combination.

For cars to maintain their status as a lynchpin of our modern lifestyle, in the face of social and environmental push back, brands have broadened the scope of their products’ influence, going beyond the highway and into the home

As the decade progressed, MINI’s presence in Milan became more and more architectural, starting with 2013’s MINI KAPOOOW! Paceman-based installation and then Jaime Hayon’s Urban Perspectives workshop in 2015. In 2016, the company showed a 30-square-metre micro apartment co-designed with Japanese architects ON design at Salone.

The installation of 2017 was even more ambitious; ‘MINI LIVING – Breathe’, by American studio SO-IL, was a micro-house erected alongside an exhibition space on Via Tortona. The next year saw another residential concept – a ‘collaborative’ dwelling – designed by London firm Studiomama, ‘MINI LIVING – BUILT BY ALL’.

By 2015, MINI and Lexus had been joined by BMW, Mazda, Ford and Hyundai, many of which were using the Salone to connect with non-industry designers and expand the perceived scope of their operations. Swiss designer Alfredo Häberli worked with BMW, while Ford and Mazda both used Salone as a platform to push their automotive design language into other categories.

For cars to maintain their status as a lynchpin of our modern lifestyle, in the face of social and environmental push back, brands have broadened the scope of their products’ influence, going beyond the highway and into the home.

Many players in the modern auto industry consider consumer design to be part of their remit, and not just luggage and furniture (although Bentley, Infiniti, Maserati and Aston Martin have all used Salone as a springboard for their interiors collections). Salone has played a major part in expanding this scope.

“Geneva used to be where we could exchange and debate ideas, Milan has now grown into that area”

However, talk to any car designer, and this sense of industry mission creep is probably still secondary to Salone’s creative pull. Klaus Busse, head of design at Maserati and Jeep Europe, as well as the Stellantis Design Studio, describes Salone as a show of three parts. “There’s the core furniture displays at Fuorisalone, as well as pop-up exhibitions across the city,” he says, “but the third part is the people who visit. It’s like fashion week in Paris – there’s so much creative energy in the city.”

Busse suggests that with the ongoing decline of the traditional auto show, Milan has taken its place. “Geneva used to be where we could exchange and debate ideas,” he says. “Milan has now grown into that area.” Busse also acknowledges that contemporary automotive design is “so much more than bending metal and moulding plastics… For a brand like Maserati, which is so incredibly rooted in Italy, Milan is doubly important,” he concludes.

Rather than serve as a bellwether for the industry, Busse and his colleagues across Stellantis use Salone as a form of concentrated inspiration. “You can never shut off as a designer – inspiration is everywhere, 24/7,” he says. “I deliberately visit non-automotive spaces – with no expectations of what I’ll find. Dubai Expo, for example, was a very relevant moment of inspiration because of the scale and immersion of the emotional experience.”

Salone is not the only game in town – Polestar’s Design Contest exists independently of Milan, for example – and countless other global design events blink on and off our calendars throughout the year, from micro-scaled to the large international expos. The Salone isn’t just a place for simple genre-flipping: cars influenced by interiors and interiors influenced by cars. Instead, its role is to mirror the complex and shifting status of car culture itself, absorbing not just the broad church of ‘Italian creativity,’ but the changing consumer understanding and expectations of design.