CCotW: Plymouth Barracuda (1973)

In search of the lost Plymouth Barracuda concept car, a victim of the ‘Butterfly Effect’

The Butterfly Effect

Spring, 1941: The legendary Harley Earl gathers his design team for an early field trip and strikes out for a nearby airfield for a peek at a secret aeroplane that is to be powered by a GM Allison engine. The team, only provisionally approved to be on base, quietly made their way across the tarmac to get a view at the radical new fighter. No cameras were allowed. The team could not get within thirty feet of the plane… but what the team saw made a deep impression.

The P-38 Lightning changed the world a little before it even left the ground

One designer, Frank Hershey, could not get the chance encounter out of his mind. He would spend the war years sketching cars – streamlined teardrops of chrome and steel, like so many designs of the era. There was one exception, however.

The P-38’s iconic twin booms and rudders inspired the iconic automotive design elements of the 1950s

Hershey’s car designs always terminated in the design element he first saw on that futuristic plane, which would soon be known as the P-38 Lightning, the “Fork-Tailed Devil” as the Germans would describe it. That element? The tailfin.

Egyptian forces cross the Suez Canal on pontoon bridges

October, 1973: Egyptian tanks roll across the Suez Canal and the Yom Kippur War begins. Fought for nineteen days, the war altered the face of the Middle East. OPEC, the cartel that controlled a large portion of the world‘s supplies of oil and was dominated by Arab states, was outraged at the American support of Israel. OPEC initiated an embargo against the West, resulting in the drastic shortage of oil, and an energy and financial crisis.

The shock of the energy crisis changed myriad energy, defense, and financial policies across the globe and also the planning decisions of major corporations, including the automobile manufacturers.

Oversimplified, but workable definition of the Butterfly Effect

The above stories are examples of the concept of the ‘Butterfly Effect’, which, oversimplified, can be described as the effect of a simple event that causes large consequences elsewhere.

It is a central tenet of chaos theory, but is also present in the studies of weather and climate (the term was coined by a meteorologist, Edward Norton Lorenz) and is also a central theme of science fiction, especially time travel stories (Ray Bradbury’s “The Sound of Thunder” being the definitive example).

The Lost Barracuda

In the case of the 1973 oil crisis, it was the “butterfly” of Egyptian tanks crossing the Suez that ultimately led to a worldwide energy crisis that would cut deep into American spending patterns, plus consumption of goods and services of all kinds.

AMC Gremlin – a struggling little compact car that got a huge boost in sales from the OPEC oil embargo

Car sales in general plummeted, but particularly gas-guzzling sedans and sports/ muscle cars. Imported cars, previously derided as toys or starter cars for college kids, enjoyed a newfound interest, as did the quirky offerings of American Motors, where Richard Teague and his design team managed, in spite of long odds, to produce a strange line of ‘so-ugly-it’s-cute’ cars like the Gremlin, Hornet and later, the glassine Pacer.

Detroit gas guzzlers like the Chrysler Imperial were phased out. Great ‘Fuselage’ styling, though

Detroit was in a panic. Smaller cars had been introduced by the Big Three a couple of years prior, but were given only scant attention. Henry Ford II was notably contemptuous of Ford’s own subcompact Pinto and the newly downsized Mustang.

To Ford and many other executives at the Blue Oval and beyond, small cars belonged in Europe and Japan, not in the wide-open spaces of America.

The balance sheets, however, did not lie; change would have to come to the Big Three, and soon. Product planning teams looked into future products and began the difficult process of altering or phasing out products.

Over at Chrysler, product planners looked through the extensive portfolio of gas guzzling cars in the lineup. A number of cars were singled out for elimination, downsizing, or radical altering.

1964 Barracuda, an iconic pony car, pictured in a not-so-subtle reference to the Ford Mustang

Plymouth’s iconic Barracuda pony car sat on the razor’s edge. It was enormously popular with the performance car guys in the company, but the finance department saw it as a drain on resources. The design team was nevertheless charged with creating a fourth-generation Barracuda that was scheduled to debut in the 1974 model year.

The third-generation Barracuda

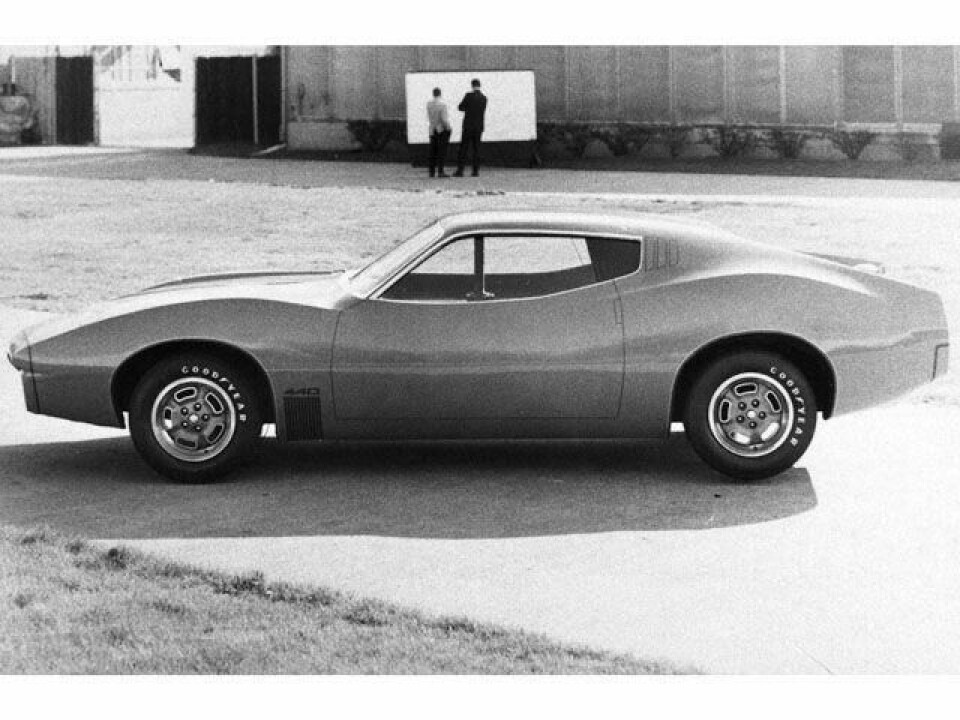

Teams began sketching, seeking ideas that would evolve the design of the Barracuda. Two themes emerged from this process. A muscular theme was championed by Shunsuke “Matty” Matsuda and Don Hood, while a smoother, flowing design was advanced by the team of John Herlitz and John Sampson. The teams began translating sketches into clay, with two themes combined on each of the two models.

The rear fascia was a close carryover from the third-gen Barracuda

The teams were in competition, but also met to critique and exchange ideas. At times the muscular themes took on a more flowing style, and then the flowing surfaces of the Herlitz/Sampson proposal would grow more muscular. Dodge designers would stop by for a look. There was a strong awareness of the importance of the project; it could influence Plymouth design for years to come.

Two models, four designs. The Barracuda team made the most of their studies in clay

Finally, the four proposals were simplified into two, and then again into one model which was then turned into a fiberglass model. This model was a blend of the muscular and the flowing themes. It drew on Barracuda design cues, but definitely looked toward more compact and muscular composition.

This clay model was the basis of the fiberglass model shown to a focus group

The finished model was shipped to a Chrysler focus group in Cincinnati, Ohio, to show to potential buyers. Plymouth designers sensed trouble. Cincinnati was the kind of conservative market where Chrysler sold Dodge sedans, not muscle cars.

Why was the car not taken to California or some other hot market for the Barracuda?

This fiberglass model was shown to a focus group. It was not a hit

Not surprisingly, the Barracuda design flopped in Cincinnati. The design team waited for the verdict without much hope.

One designer remembered the Ohio debacle like this: “That wild body went to Cincinnati of all places, and it was a disaster. I came back from Cincinnati and realized it was all over; management didn’t want muscle cars anymore. It was the saddest day of my career at Chrysler.”

Finally, the word came down from on high. The Barracuda would not be reworked for the 1974 model year. A mild refresh was ordered. Designers were disappointed but not surprised. The Cincinnati focus group experiment seemed stacked against the Barracuda from the beginning. The planning and finance groups just needed a nail to hang their hat on.

As if to punctuate the Barracuda’s demise, the fiberglass mock-up fell off of the forklift as it was returned to Detroit, and the model ruined. The symbolism wasn’t lost on anyone.

The proposed refresh was reminiscent of the Roadrunner Superbird

The Superbird itself is a legend now, a sales disappointment then

Designers were instructed to give the Barracuda a nose job, a minor alteration that was a bit reminiscent of the Roadrunner Superbird, but it was all for naught. The Chrysler planners ultimately decide not to extend the Barracuda’s life at all. The Roadrunner would continue, but as a watered-down version of the Fury, and then, ignominiously, a version of the Volaré, a downsized Plymouth midsize coupé.

Chrysler had killed its muscle cars.

Cruel Irony, Screaming Chicken

Ironically, Chrysler killed the Barracuda and Challenger at the very moment when pony car sales were poised for a rebound. After the initial oil shock, Detroit managed to engineer effective responses to the government’s new pollution and safety regulations, as well as achieve some modest gains in fuel mileage. Pony and muscle car sales began a slow and steady rebound.

The Butterfly Effect: A movie about a beer smuggling outlaw and a runaway bride revives the pony car, and Pontiac

Also, in 1977, a movie became a hit that launched an unlikely spike in pony car sales. Smokey and the Bandit was the story of a redneck beer-smuggling Robin Hood racing one step ahead of a corrupt Sheriff to deliver a precious load of Coors beer (!) to a thirsty client.

The movie was basically one long car chase, and Bandit’s car was a new (not actually released) Pontiac Firebird Trans Am, complete with the iconic “screaming chicken” Firebird emblem on the hood. All that screen time created a hero out of the car itself-as well as its two occupants, Burt Reynolds and Sally Fields. The movie was the second-highest grossing movie of the year (behind Star Wars). Sales of the Trans Am skyrocketed.

Firebird Trans Am with a “Screaming Chicken” on the hood. An unlikely star

By 1979, Firebird sales accounted for two out of every five Pontiacs sold. The car would save Pontiac, at a time when GM was considering closing the division altogether. It was an ‘I told you so’ moment for Firebird purists within GM, who recalled (and did not forgive) the effort to kill the Firebird nameplate back in 1972.

Ford’s Mustang and Chevrolet’s Camaro sales piggybacked on the success of the Firebird. Good times, but Chrysler had to sit on the sidelines. Carl Cameron, a designer in the Dodge studio later recalled, “We got out of the only part of the market that grew. We abandoned it, and I always thought that was a mistake.”

Indeed, Chrysler would soon face bankruptcy and need government loans to bail the corporation out. The sales of all their cars lagged behind other companies for years, even when their products improved. It was two decades before Chrysler would return with a pony car of its own. By then, Plymouth was gone and with it the Barracuda.

Today’s Dodge Challenger – old-school badassery for Baby Boomers

The butterfly effect teaches us that design doesn’t happen in a vacuum. One likes to dream of a pure design environment, free of the contaminants of program, finances and politics. Ultimately though, what designers of all types do is design for life – in all its messiness – and, hopefully, make it better. This means understanding that the design world is subject to strange twists of fate that animate, and haunt, the rest of life.

To master design, one must get out of the studio, out into life, and scan the horizon.

There is a butterfly out there, flapping its wings… or is it a screaming chicken?