CCotW: Triumph TR250K (1967)

A Peter Brock classic – the TR7 that might have been

Peter Brock needs no introduction to readers of Car Design News. The legendary designer and racer, whose credits include the original Corvette Sting Ray, the Shelby Cobra, and the De Tomaso P70, was already famous back in the 1960s when his racing bona fides drew the attention of many an automaker.

The Triumph TR-5 – handsome, but saw its market share diminish in America in the late 1960s

The story begins with W.R. ‘Kas’ Kastner, Director of Motorsports for Triumph in the late 1960s. Based in Southern California, the centre of sports car racing in America, Kastner watched with alarm as new Japanese imports began overtaking Triumph sales in the United States. Triumph had a solid reputation in both motorcycles and sports cars, but the young upstarts from Japan were getting all the attention.

He broached the subject with his friend, competitor, and, fortuitously, neighbor, Peter Brock. Brock, after his experiences with Carroll Shelby and Alejandro De Tomaso, had formed his own racing team, Brock Racing Enterprises. He raced Toyotas, Hinos, and by 1967, Datsuns – first the 2000 roadster, and then the legendary 240Z.

Peter Brock’s design for the Hino Samurai is an underrated classic. Note the adjustable wing

Brock listened to Kastner’s dilemma. Never one to miss an opportunity, he saw that a competition battle between Triumph and Datsun would benefit both racing programs, and, by extension, both manufacturers. There would be other formidable rivals too – factory-backed Porsches and Toyotas, along with excellent privateer teams, filled the racetracks with great cars and exciting races.

Brock also realised, as did Kastner, that if Triumph was going to be serious about competitive racing it needed to improve the quality of its cars. Toward this end, the two decided to design and build a prototype based on a Triumph IRS TR-4 chassis. The project would start in late 1967 with the goal of racing in the 12 Hours of Sebring the following spring. It would be a rush project in the extreme, with neither the cash nor the time to realize all of their dreams for the car.

Brock’s clay model, just after the original coupé roof was removed. There was only time to build a roadster

Kastner, with only a crude plan and a quickie Brock sketch of the proposed car, traveled to England to ask Triumph executives for working capital. He managed to pry $25,000 out of a reluctant Triumph. Meanwhile, Brock had secured a promise from Car and Driver magazine to publish the completed racer on its cover, and began laying out the car, using a stock TR4 chassis as the core for the new prototype. As Brock described it:

“He (Kastner) just gave me a new bare chassis out of stock and I went from there in laying out the cockpit. All the design and fabrication work was done at BRE [Brock Racing Enterprises] by our best fabricator, George Boskoff. We set the engine back as far as practical to improve weight distribution and then built an entire sub-frame of small tubes on top of the stock TR4 chassis to increase stiffness. Later, Kas added all of the suspension, engine and running gear based on his vast experience with the TR4s.”

The TR250 cockpit frame – the windscreen frame provided torsional stability

With the chassis laid out, Brock then focused on the cockpit design, hoping to create a better environment for drivers pushing through the rigours of a 12-hour endurance race. He explained:

“I placed a lot of importance on the layout of the cockpit from a driver’s point of view – as driver comfort allows a certain amount of ‘relaxation’ at speed. I call it ‘dynamic ergonomics’. The K-car has more room for driver and passenger than the production Triumph TR4. The high back behind the cockpit was revolutionary in its time; this feature was essential to offset the aerodynamic loss encountered by removal of the roof. As a side benefit we gained useful space for the spare tire, mechanical components and luggage.”

A sleek shark-nosed design referenced Brock’s Corvette Stingray days

Wrapped around this cockpit was a wedge-shaped body that spoke of Brock’s Corvette Stingray. The low, long snout and the shape of the body sides brought Corvettes of the early and mid ’60s to mind. The steeply-raked windscreen got attention on and off the track. It wasn’t just to hold the windscreen glass, however. First designed for the Hino Samurai, the frame was designed to add torsional stiffness to the car. Brock had hoped to embed this frame in a closed coupé, but there just wasn’t time – a roadster was finished instead.

An unusual raised rear deck partially compensated for the aerodynamic disruption of the open cockpit

The raised rear deck, deemed essential for aerodynamic purposes, allowed for extra storage as noted above, and partially compensated for the disruption of airflow over the open well of the cockpit. At the back of this deck was a spoiler that could be raised and lowered by the driver during the race. Although meant to be fully adjustable, in fact, in all races it was completely raised. The rear fascia dropped off abruptly, a Brock version of a Kamm back.

The rear spoiler (lower) was controlled by a lever to the right of the gear shift (top)

A 2.5-litre six-cylinder Triumph engine with three Italian Weber carburettors powered the 250K. The carburettors were chosen because the team was more familiar with them than the English SUs. (Triumph was already introducing fuel injection into the TR5). A number of custom parts, along with a few adopted other manufacturers’ parts, completed the engine. The radiator, for example, was from a Corvette, appropriately enough. The engine was moved back nine inches to allow for a lower nose.

Peter Brock (left) and his team with the completed TR250K

Construction went on until the very last minute, and there was only one day of testing at the Willow Springs test track before the car had to be shipped to Sebring. The car had acquired a name finally – TR250K. It was designated TR for Triumph, 250 (for its engine displacement), and K for Kas Kastner.

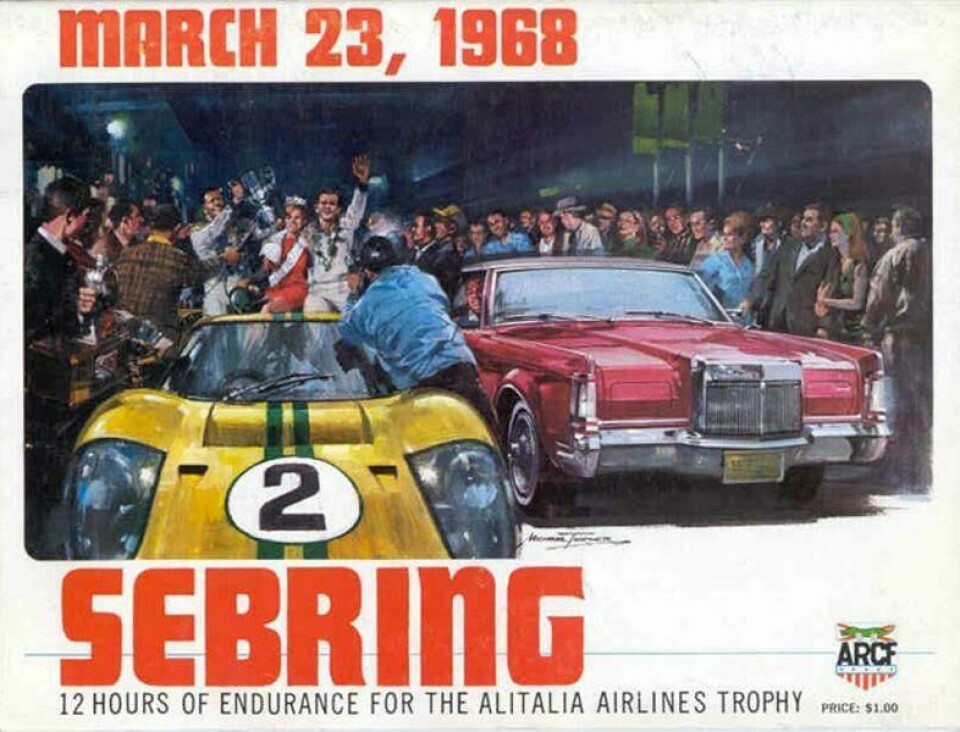

Cover of the Sebring Race program for 1968

Once at Sebring, the TR250K would be entered in the Group 6 Sports Prototype Class, along with four (!) Porsche 907s (here is an in-depth look at the whole field). The race started well, and the TR250K pulled out a substantial lead. But then a rear tyre mysteriously stripped off the rim, and the car spun out. Although there was no damage to the body, the rear suspension was damaged beyond what could be repaired at the track. The TR250K’s racing days seemed over just two-and-a-half hours into its first race.

Subsequent forensic analysis by the team revealed that the wheels, adopted from a Jim Hall Chaparral car and modified to fit the Triumph hubs, had cracked and then split along the stud circle. One tiny crack had brought the whole program to an end.

Car and Driver delivered on their promise to make the TR250K their cover car for April 1968

Still, Triumph was impressed, and Car and Driver did feature the car on its cover with an enthusiastic review in a lead article. The car would go to the Detroit show and many others around the country.

Brock and Kastner hoped Triumph would adopt the car as the successor to the forthcoming TR6, but it never happened. Brock was left with a sour taste in his mouth and claimed the production TR7 was a pale imitation of his design.

More official histories of the TR7 credit Harris Mann with the design of the TR7, a car that was hastily designed and built for the American market after the TR6 could not be adapted to meet new American regulations. The car does fit in with many of Mann’s wedge-shaped designs of the time.

View of the cockpit – form following function. The steering wheel was smaller in the original racing car; this one was for the show circuit

The TR250 was eventually returned to Brock, who had more invested in the car than anyone (he had worked tirelessly to get additional sponsorships, as the Triumph seed money ran out quickly). Brock would soon sell the car to finance other projects.

The car dropped out of sight for a couple of decades, eventually ending up at the Blackhawk museum near San Francisco, in their reserve collection, painted a brilliant red.

The TR250K, now owned and restored by the Hart family of Seattle

The Hart family of Seattle Washington would buy the car and undertake an extensive restoration. It can still be seen in exhibition races and at concours around the US as another testament to Peter Brock’s genius, and a tantalising glimpse of ‘what might have been’ at Triumph.

(If you want to see the TR250K actually racing, there’s some charmingly clunky, silent 8mm home movie footage here – it appears in the pits just after the two-minute mark, and running at 9:53.)

The attractive, if badly flawed, Triumph TR7