Concept Car of the Week: Chrysler 70X (1969) and Cordoba Del Oro (1970)

Defining the “Fuselage” Aesthetic for a new decade at Chrysler

In 1961 Chrysler hired Elwood Engel away from Ford where he had held the position of Director of Advanced Design. It was a good match for both parties. Virgil Exner, who spearheaded Chrysler’s “Forward Look” in the latter half of the 1950s, found his radical tail-finned creations rapidly falling out of style. Exner’s health had become increasingly precarious, too. Engel, for his part, had been passed over for promotion to Vice President For Design in favor of Eugene Bordinat. Engel’s retiring boss, George Walker, who was well connected throughout the industry, quietly arranged an interview with Chrysler’s executives. Engel was the right man to lead Chrysler forward in a new decade that would in many ways be defined by Engel’s greatest creation, the iconic Lincoln Continental of 1961, and so was hired as Director of Design.

1964 Chrysler Imperial Coupe

Once at Chrysler, Engel would waste no time in establishing a new aesthetic, with the Typhoon concept car of 1962 and the Chrysler Turbine car of 1963. These cars helped the public look past the disastrous production offerings of 1962-63, the design of which had been set before Engel was hired. Engel’s first production impact was on the 1964 cars, of which the Chrysler Imperial is the standout. The previous Imperial had been a ponderous, overwrought assemblage of styling details dating as far back as the mid-1950s. The new 1964 model was a crisp, clean box with formal lines in the spirit of the ‘61 Continental, but stylistically more tailored and updated.

Engel’s design work finally hit its stride in the mid-sixties, and by 1968, when a refresh of Chrysler models was needed, a new design language was ready to emerge. The styling of the next generation of cars, particularly the full size models, was called, “fuselage styling” or the “fuselage look”. The style’s characteristics can be summed up in the following text from a Chrysler advertisement of the time:

”Your next car can have a fuselage-frame that curves up and around you in one fluid line. Close the window and the arc is complete. From under the doors to over the cockpit. Inside your next car, a cool, quiet room of curved glass and tempered steel. Soft, contoured seats and easy-to-read gauges. A controlled environment for you and each individual passenger. Your next car can have no protruding chrome, bumps, knobs, gargoyles, or wasted space. It can be an extension of your own exhilaration of movement. Your next car can be a car you can move up to. Without effort. Your next car is here. Today.”

More than just a bit of advertisement patter there, but the text actually encapsulated very well the spirit of the new design language. The fuselage look was one of bold form and mass, with a minimum of surfacing, simple glasshouses that were strongly subordinate to the overall body shape, and with minimal brightwork, usually concentrated on the front and rear fascias. The fuselage look always worked best on full sized cars like the LeBaron and Imperial (two of the largest, heaviest production cars ever built), and it was decided to create concept cars that could best show off the new design language as it would evolve over the next few years, or perhaps a decade or more.

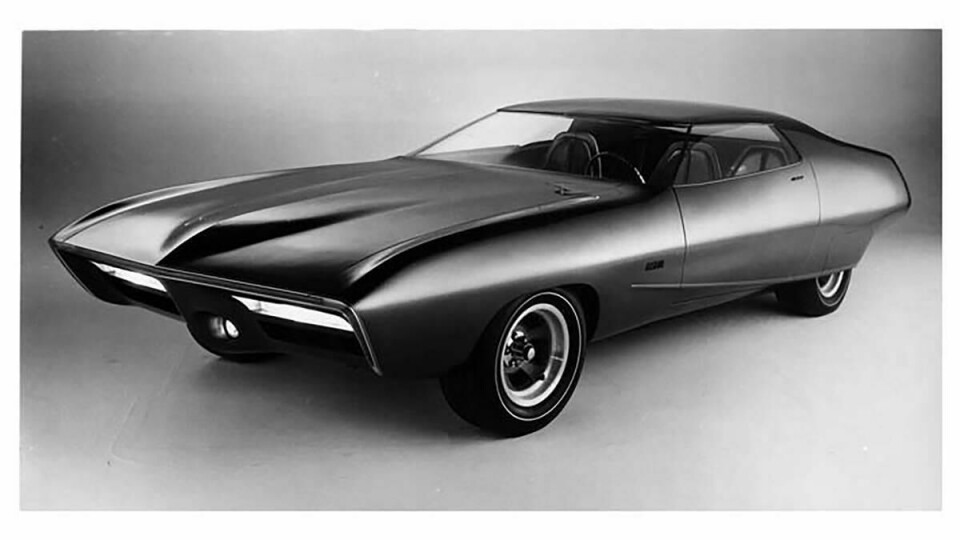

1969 Chrysler 70X

The first of the concepts was the 1969 Chrysler 70X, a preview of a near-future Chrysler executive sedan. The car is distinctive by its dreadnought-class size and massive proportions. Pantograph doors open to allow for a generous entry sequence to either front or rear seats. The fuselage look with clean (although huge) massing, with minimal chrome is much in evidence here. And while some Chrysler products had been criticized for betraying too much of a Ford influence – the result of Engel’s decade-long tenure at the Blue Oval – it was a General Motors influence that made itself known here. The front fascia with its faceted, sculpted nose was reminiscent of the 1967 Cadillac Eldorado, while the rear fascia reminded many of the 1968 Chevrolet Impala. In between, however, it was all Chrysler – the massing, the glasshouse, which had an unusually small C-pillar with a glazed rear windscreen surround.

The next year, Chrysler introduced the Cordoba Del Oro, a two-door full size personal luxury car. Again, the size was massive and the form relatively simple, although a wedge shape across the front and sides was reminiscent of the ill-fated Chrysler Norseman concept of the 1950s, which had a similar nose and side sculpting. Under the wedge at the front were two rectangular headlamp banks. The body also featured massive C pillars that held up a cantilevered roof, again like the Norseman. The whisper-thin A pillars were mere frames for the windscreen and side windows, they no had structural function. At the rear, the massive rump was devoid of taillights, which were mounted at the upper edges of the rear windscreen, anticipating a safety feature that would not be required until the mid-1980s.

Seen on the rotating podium at the Chicago shows, both the 70X and Cordoba Del Oro looked remarkably well proportioned for their gargantuan size. The Cordoba looked especially sleek, almost like a (much) larger, more menacing Plymouth Barracuda of the time. But there was no hiding the fact that these were very large cars, and from certain angles the weight and mass of both cars seemed to overwhelm any pleasing design characteristics either car might possess. Also, the Cordoba’s awkward name – straight out of the 1950s – undercut some of the poetry in its design.

Both the 70X and Cordoba Del Oro would influence Chrysler’s production models of the early 1970s. The 70X would influence the evolution of their large sedans and later mid-size sedans in the post-1973 era. The Cordoba would find its expression in the early 1970s Plymouth Satellite, albeit in a much tamer package and trim.

The whole fuselage look was doomed however by the oil shock of 1973. The large cars upon which the style depended would rapidly disappear from the automotive landscape, as smaller, more compact cars took their place. And the father of the whole fuselage look, Elwood Engel, would retire in 1973 and be replaced by Dick Macadam, under whose leadership Chrysler was somewhat adrift, without a strong design language until Lee Iacocca came on board in 1978.

Syd Mead’s 1972 Imperial LeBaron, nicknamed ‘Fabulon’

Can the fuselage design language have anything to say to us today? Apparently so. Witness the emergence of Mercedes’ “Sensual Purity” design language, which emphasizes a simple, bold form over the proliferation of creases and character lines that has dominated automotive design for the last decade. Commenting recently on the new design direction at Mercedes, Gordon Wagener said, “Form and body are what remain when creases and lines are reduced to the extreme…. Design is also the art of omission: the days of creases are over.”

Elwood Engel couldn’t agree more.