Concept Car of the Week: L’Oeuf Electrique (1942)

The mother of all bubble cars has something to say to us about the car of the future

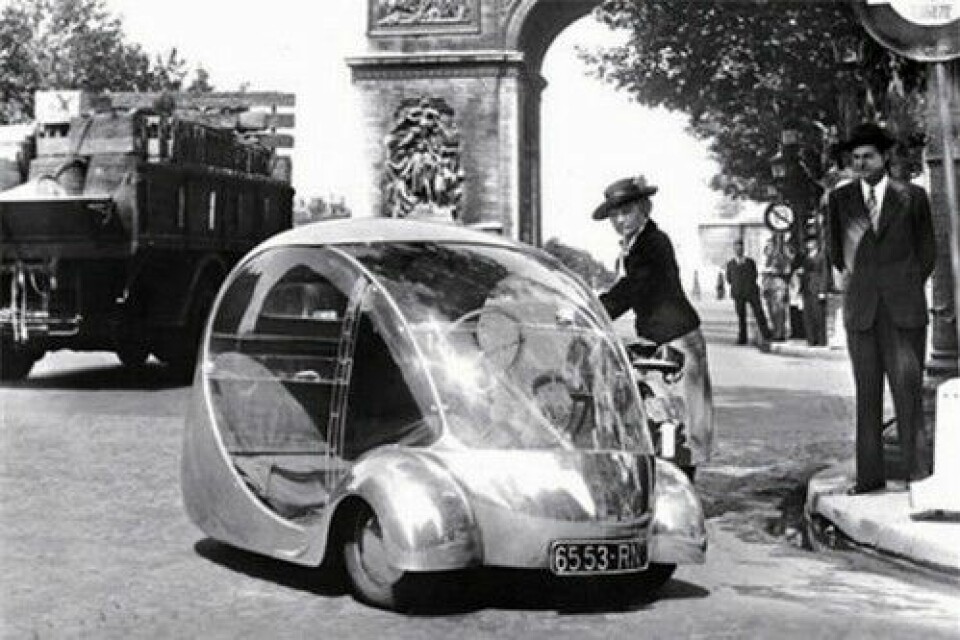

Paris, 1942: at the darkest time of the Nazi occupation, the City of Lights lay under a blanket of darkness. The streets once teeming with automotive traffic were empty except for military vehicles. Petrol shortages meant that horses and carts returned for delivery duties.

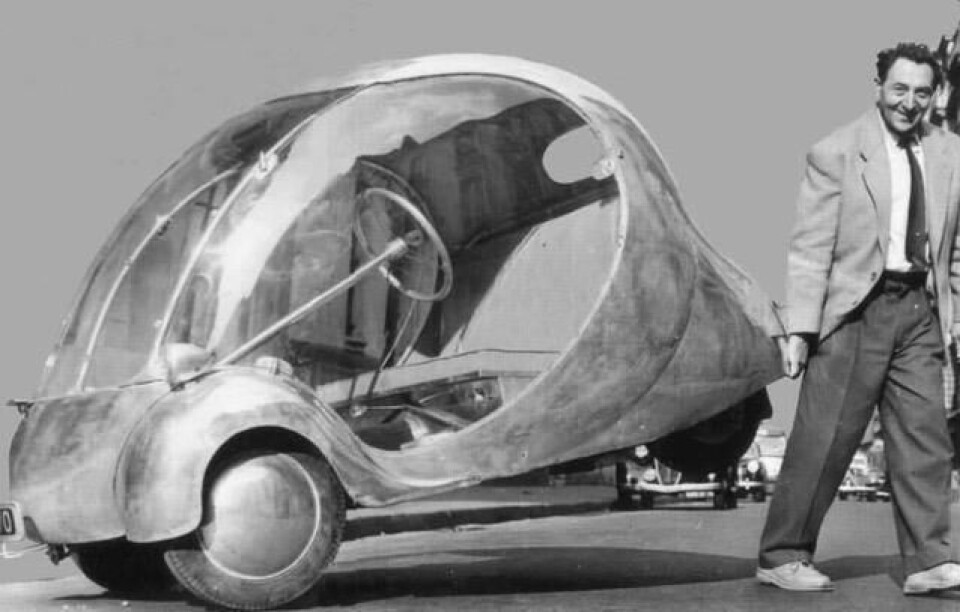

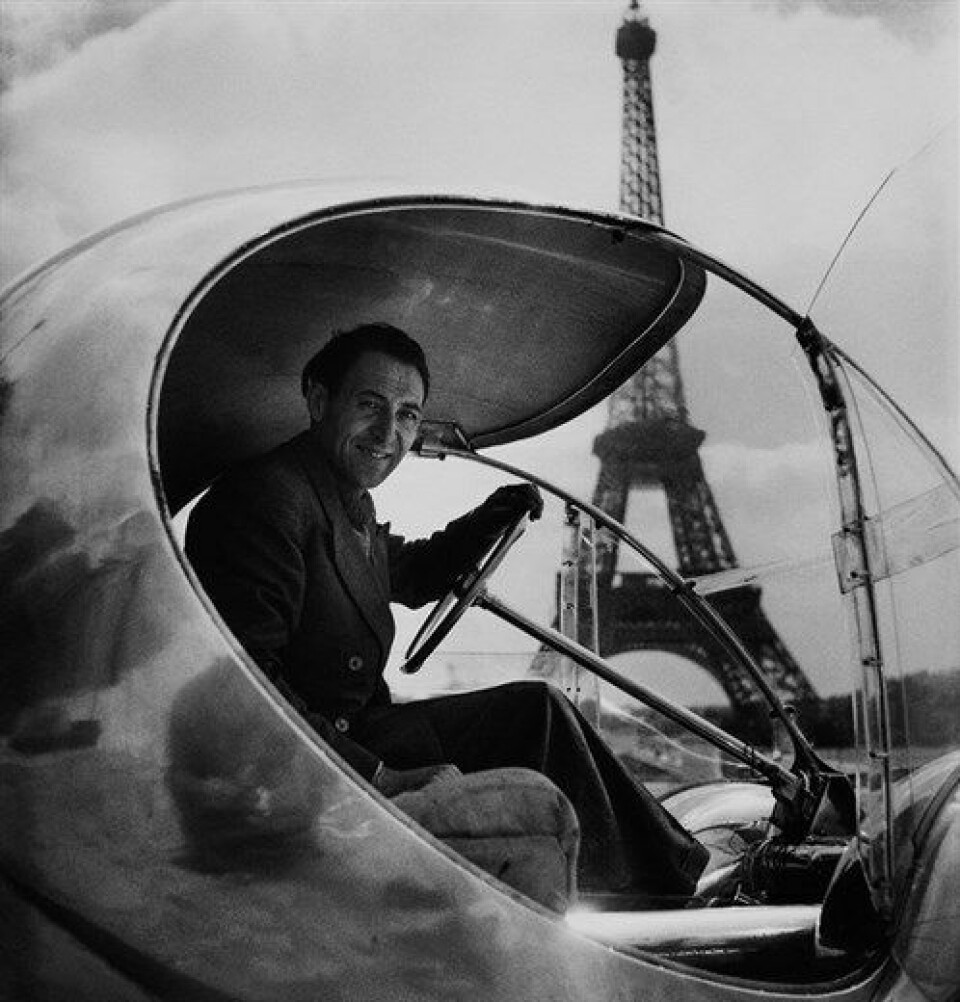

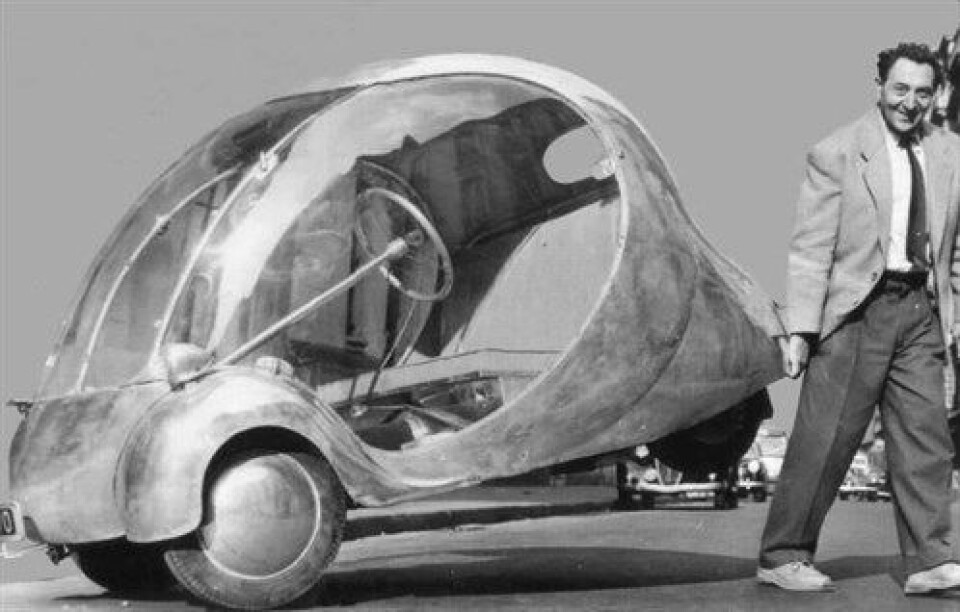

But then reports began circulating about a strange shiny little car that silently flashed around the streets. This turned out to be the invention of engineer Paul Arzens, who had decided to create a lightweight, three-wheeled electric runabout for the city, using a minimal amount of material. The little car soon acquired a name, L’ Œuf (The Egg), and then subsequently L’Œuf Electrique (The Electric Egg).

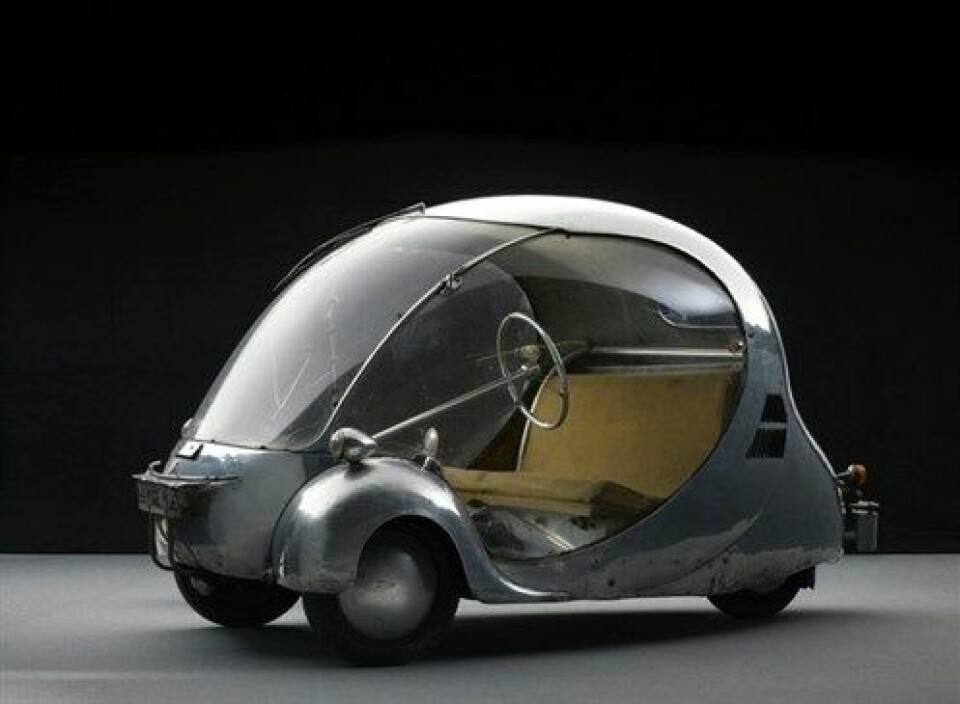

The Egg consisted of a bulbous aluminum and Plexiglas body that enclosed a minimalist two-person interior. The glasshouse was enormous for a small car, and included full Plexiglas doors for excellent forward and side visibility (the rear window was a tiny oval porthole). The remainder of the body was built of aluminum, hand-formed into a dimply egg shape, similar to that of the Porsche Gmünd cars which came a few years later. The Egg tapered to a blunt point at the rear, where the aluminium covered the third wheel and electric motor.

The whole ensemble was amazingly lightweight. The body was only 60 kilograms, weight increasing to 90 kilograms with the electric motor. With batteries added, the whole car weighed only 350 kilograms – about the same as a pre-war cycle car.

The interior was minimalist in the extreme – a simple bench seat over a wicker frame, a steering wheel, and no gauges or instrument panel. All other interior fittings were also omitted to save weight.

Only an engineer like Arzens could have scrounged the materials for the Egg during the privations of wartime Paris. However, the value and scarcity of aluminum and Plexiglas meant that only one prototype could be built. Nonetheless, Arzens received quite a bit of attention for the Egg, which he claimed could travel some 100 km at 70 km/hr, or at 60 km/hr with two people in the car.

After the war, Arzens stepped away from the electric car and proposed a simple ICE vehicle to be built for a minimal price. But it was never developed, and by 1947, Arzens was working for the French National Railway Company (SNCF) designing locomotives and rolling stock. Even here, at an entirely different scale, his experience with electric cars would influence his designs, and one of his locomotives, the CC7107, would set a speed record for electric locomotives that would stand for over 25 years.

But Arzens never forgot his beloved Electric Egg. He kept it in his collection for the rest of his life, taking it out for the occasional drive. The Egg has since been passed on to the Cite de L’Automobile museum in Mulhouse, France, where it awaits restoration. It was recently loaned to the ‘Dream Cars’ exhibition which toured in the United States; visitors to that show voted the Egg one of their favourite cars on display, citing its simplicity, large glass area and effervescent joie de vivre as reasons they would buy one today, if available.

And therein lies the enduring lesson of the L’Œuf Electrique, the tiny bubble car now almost seventy-five years old: simplicity, lightness, urban scale, and most of all, that joie de vivre, are the elements we must bring to design of the city cars of tomorrow.