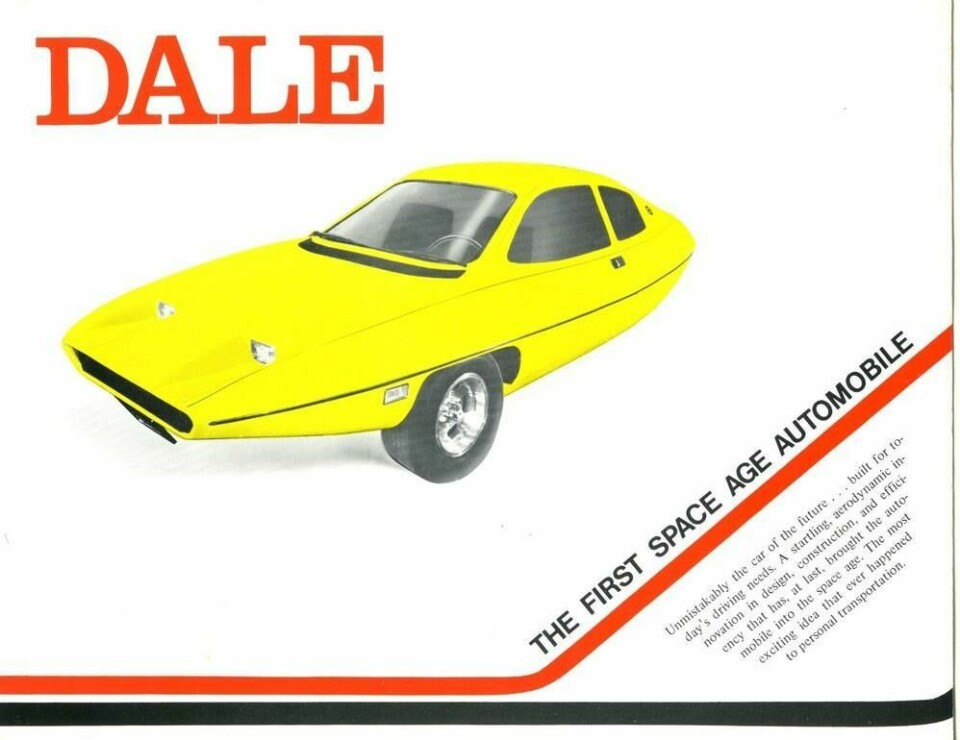

Concept Car of the Week: The Dale (1974)

Grifts, murder, a transgender con-artist and a micro car – the story of The Dale concept car proves life is stranger than fiction

Dale Clifft was a machinist and small-time inventor who loved to modify speedboats and motorcycles. And when the oil crises of 1973 hit Southern California, Clifft was sure that he could design a commuter vehicle that would cut his petrol costs. So he cobbled together a three-wheeled car out of an old motorcycle engine on a home-built frame and fashioned a body out of red metalflake naugahyde.

Clifft became a fixture of sorts in the San Fernando Valley of Los Angeles, puttering around in his eccentric little vehicle. Though his car was primitive, people admired his shade-tree mechanical ingenuity and homespun defiance to the fat cats of OPEC.

One night, though, while Clifft and his wife were eating dinner at his favourite restaurant, a man came up, introduced himself, and offered to arrange a meeting with an investor that could take Clifft’s idea to the next level.

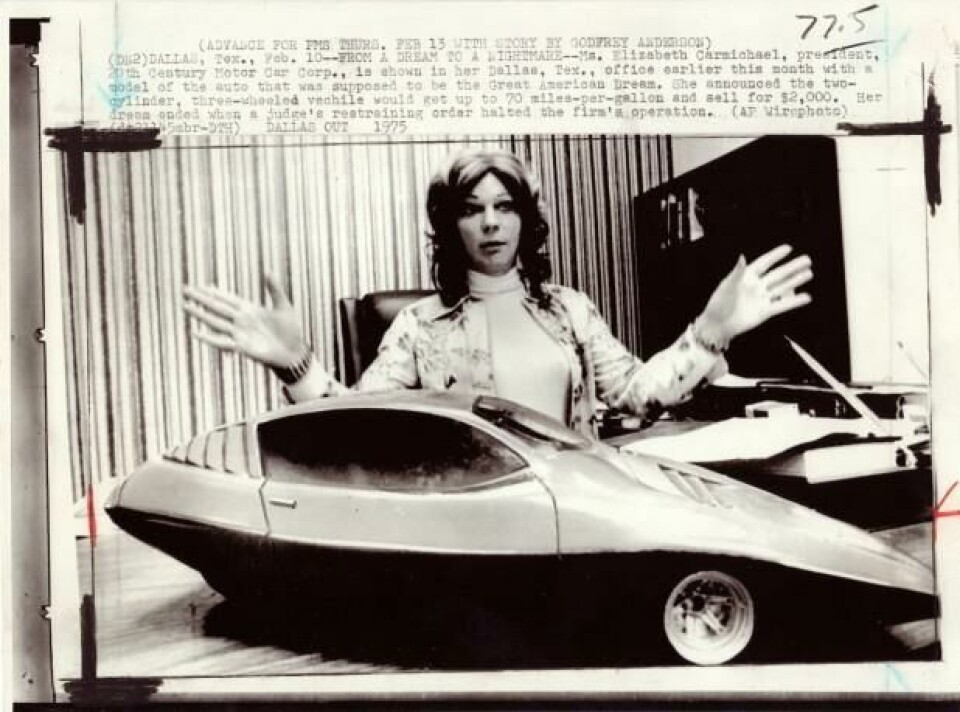

The next week, Dale Clifft found himself sitting across the table from a large, stylishly dressed, and yet, formidable looking woman – Geraldine Elizabeth (Liz) Carmichael, who spoke enthusiastically in a husky voice about his little car and the possibilities of transforming the machine into the next great automobile; the perfect solution to the oil crisis.

Carmichael’s own background, she claimed, prepared her for the challenge – a farm girl raised in the Midwest (like Clifft), skilled in the construction and repair of machinery, a mechanical engineering degree from Ohio State University, an MBA from the University of Miami, the mother of five children, widow of a NASA engineer, the holder of a patent on a special type of self-skinning foam.

Carmichael suggested some minor alterations to Clifft’s design and soon they were working together to construct a prototype. Carmichael established the Twentieth Century Motor Car Corporation (TCMCC) and began heavily promoting what she called a revolution in automobiles.

Soon Clifft’s design took shape, first in the form of a scale model then a full scale prototype that was installed in Twentieth Century’s new offices on Ventura Boulevard, near an upmarket part of suburban Los Angeles. The car mock-up could be seen from the street and passers-by were invited in to view the future of the automobile, although they were kept at a fair distance by a roped circle which allowed only a general view of the car.

Clifft signed a contract for three million dollars to license his design, with a thousand-dollar retainer and a promised initial payment of two hundred thousand dollars for consulting services during the ramp-up to production. Carmichael had also rented a hangar at Burbank airport which she promised to transform into an ultra-modern research and production facility. She invited Clifft to work on prototype development there.

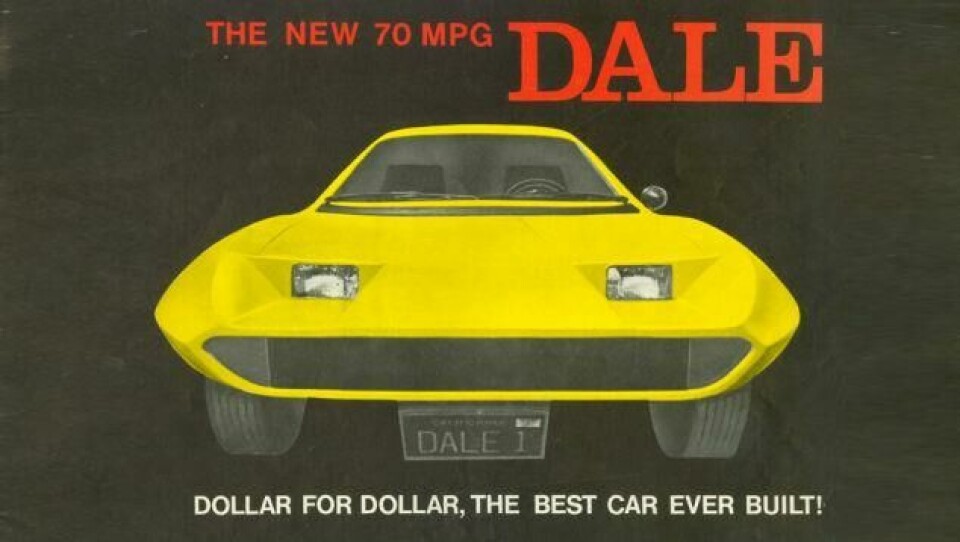

The little commuter car that Twentieth Century planned was a two-seat, three-wheeled commuter with advanced handling and safety features. It would deliver superior fuel economy – in the range of 70 miles per gallon – with a BMW horizontally-opposed 850cc motorcycle engine driving the single rear wheel.

The monocoque body would be made of a “rocket structural resin” which was said to be safe in the event of a crash, and was placed over a lightweight space frame. The engine and seats were to be placed within the triangle of the space frame and thus were (in theory) protected during a crash. The windows would be made of Rigidex, a material many times stronger than standard safety glass. The whole assembly was to weigh less than a thousand pounds.

Carmichael claimed all internal wiring would be eliminated, with space-age circuit boards built in to power instruments and an air conditioner and heater – you could just plug the desired components in as needed.

And, best of all, the car would be priced at just under $2,000, some 20 percent less than a basic Volkswagen Beetle. It would be named the Dale, in honour of its creator.

Carmichael was a genius at promotion – a tireless, brash, non-stop talker and a master cultivator of the press. She arranged interviews with local newspapers, national wire services, and popular magazines, often receiving glowing praise. She was a dramatic (some say intimidating) presence at nearly six feet tall and about 175 pounds. She was fond of boasting. “I’ll knock the hell out of Detroit,” she said. “I’ll rule the auto industry like a queen.”

Carmichael exhibited the car wherever it would garner lots of attention and perhaps attract money from an investor or two. She even got the car to be featured as a prize on the popular television game show The Price is Right. The Ventura Boulevard headquarters was soon humming with TCMCC investor relations people and potential dealers and customers, all buzzing around the odd-looking little car.

Dale Clifft had been starstruck at first by his newfound celebrity, but then grew alarmed about Carmichael’s increasingly outlandish claims about the capabilities of the Dale. Some of the shady characters in the front office made him uneasy too.

Clifft brought his concerns to a meeting with Carmichael. The discussion turned into an argument and Carmichael, who had a short temper at the best of times, fired Clifft on the spot and barred him from all TCMCC properties. Clifft was now on the outside looking in. He still had his licensing contract, but no way to assess the daily progress of the car or the company.

The Carmichael/Clifft split was just one episode in what would be a rapid unraveling of the TCMCC. The California Department of Corporations and the Department of Motor Vehicles were demanding licenses for sales, manufacturing, and other regulated corporate activities. Carmichael had not bothered to apply for any of these. The State began to threaten to close TCMCC.

There had been plenty of funding from investors and franchisees, but somehow the company was always short of money. Then two of Carmichael’s associates got into an argument one evening at the Ventura Boulevard headquarters, and it was settled with guns. Before it was all over, one man was dead, and another was on the run. Police later revealed that the two had been cellmates at San Quentin prison.

Liz Carmichael, sensing the end was coming, moved to Dallas and re-established the company there, still trumpeting her message of the value of the Dale as a vanguard of a new generation of hyper-efficient cars. But the police, and now, the FBI, had other ideas. They raided her house in Dallas only to find her gone again, having left a number of curious personal items behind, including a collection of wigs, well-padded brassieres and tubes of hair remover.

Finally, in Miami, agents finally caught her after a madcap chase that lasted for hours and finally ended in her bedroom, where a police dog named Otis sniffed her out from behind a curtain.

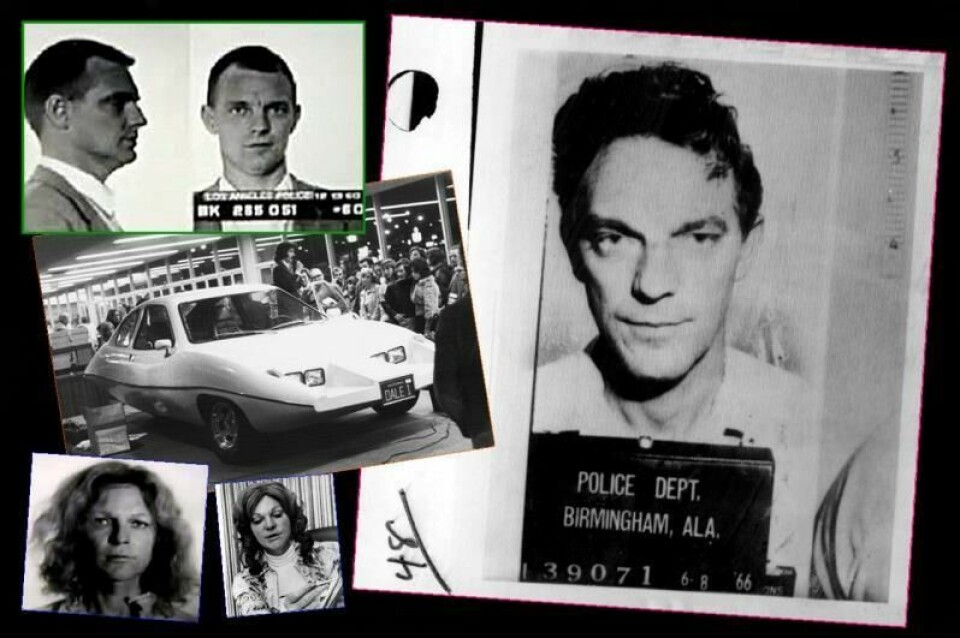

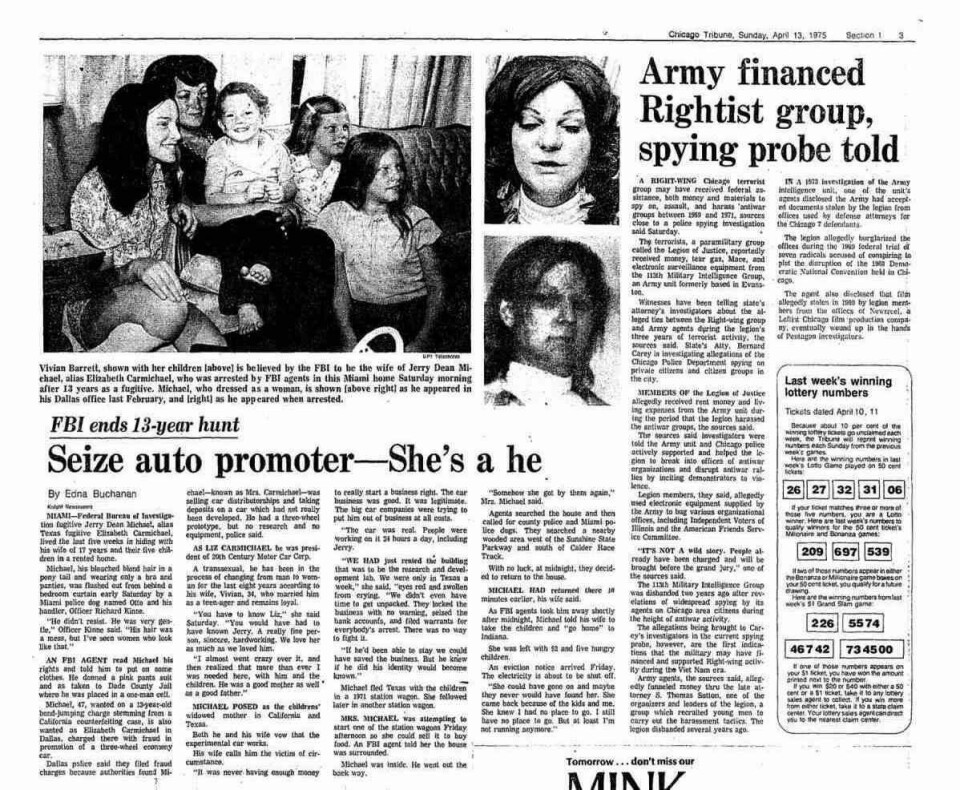

At the police station, fingerprints and further investigation revealed what many had long suspected. Carmichael was not a woman but a man, Jerry Michael, a long time felon, counterfeiter and confidence man, who had been on the run since 1961. The children found in his house were his, but he was their father, not their mother. The woman that claimed to be their mother, was indeed, their mother, and Jerry’s wife, Vivian. Liz Carmichael had always introduced Vivian as her personal secretary.

Jerry Michael claimed to be undergoing sex reassignment surgery and hormone treatments. His wife verified the claims, claiming she and her children staying loyal to her husband, even through his transition.

Carmichael was returned to Los Angeles and placed on trial for a battery of charges including grand theft, securities fraud, and a host of charges relating to operating a manufacturing corporation without proper licensing. Multiple agencies from the City of Los Angeles, the City of Dallas, the State of California, and the Federal Securities and Exchange Commission participated in the trial.

As the trial progressed, the truths everyone suspected came out. There had never been any serious effort to produce a car, and no research or production facilities were ever formally established. The money collected from investors had mysteriously disappeared. The Dale prototypes were little more than fibreglass shells attached to wooden frames, and even the wheels were nailed onto timber axles. The one engine that finally got installed in a ‘running’ prototype was from a Briggs & Stratton lawnmower.

Liz Carmichael showed up to the trial every day in stylish dresses and skirts and gave forceful testimony in her own defence. She gave no quarter on any charge or legal argument, insisting she had been framed, or railroaded by a conspiracy of the Big Three car companies in Detroit. But the jury wasn’t buying it. In the end, Carmichael and nine of her associates were convicted on nearly all of the charges.

All the while, Dale Clifft was in the gallery, watching the proceedings. Astonishingly, despite being a known flight risk, Carmichael managed to raise $50,000 bail and fought the convictions on appeal for the next four years. Then one night she disappeared, and for nine years was once again on the run. She was finally recognised by a member of the public after an episode of the TV show Unsolved Mysteries which detailed the strange case.

She was arrested, still living as a woman, running a flower stand with several children in a small town in Texas.

The name of that town?

Dale.

Dale, Texas.

Truth is so much stranger than fiction.

Postscript

Dale Clifft was never implicated in the TCMCC fraud case, as he was one of the principal victims, having been cheated of millions of dollars. He continued patenting small inventions until his untimely death at age 49 in 1981.

Jerry Michael/Liz Carmichael spent a few years in a men’s prison, paid some restitution, and died of cancer in 2004. Vivian Michael doubtless knew of the fraudulent activities of her husband (she was the ‘personal secretary’) but was never charged, probably out of compassion for their five children.

All three prototypes of the Dale, plus the scale model, still exist. The one prototype that can be seen by the public is at the Petersen Museum in Los Angeles. It is the car pictured below – part of the Petersen’s ‘Vault’ collection.