Concept Car(s) of the Week: The Corvette Mako Sharks

Wicked-looking concepts that predicted the future of Chevrolet’s iconic sports car

One day in 1956, Bill Mitchell, who would soon become GM’s design chief, pulled up at a red light not far from the GM Technical Center. Beside him was a Ford Thunderbird driven by a young designer GM had recently hired and who had quickly made a name for himself with interesting ideas for the 1959 Pontiac and Chevrolet models.

Mitchell admired the work of the young designer, but was not pleased that he had had the temerity to drive a Ford car onto the GM campus, so he decided to show the kid a little GM muscle. He revved the engine in his bright red supercharged Pontiac and shot off as soon as the light turned.

Big mistake.

Mitchell looked back, expecting to see the Thunderbird fading in the rearview mirror. Instead he saw a flash beside him then saw the Thunderbird accelerating out of sight. Mitchell never caught him.

Abashed, Mitchell would seek out the young man the next day and demand that he pull his Thunderbird into the garage for an inspection. There he was shocked to see that the kid had decked his T-bird out in full racing regalia – racing-spec engine, heavy-duty shocks, a stripped interior and a full roll cage.

Bill Mitchell had just met Larry Shinoda – hot rodder, racer, designer, and incorrigible badass.

Larry Shinoda beside his championship-winning racer, which sported the slightly dubious nickname of ‘Chopsticks Special’…

Larry Shinoda was born in Los Angeles in 1930, and was interned with other Japanese Americans at the remote Manzanar camp during World War II. After the war, he got involved with Southern California’s hot rod scene, and would win the first NHRA Nationals races in Kansas in 1955. Shinoda had enrolled at Art Center in the early 1950s, but had found the program too constricting and was dismissed. Looking back on the experience, Shinoda would recall: “I didn’t fit in there; my ideas and desires weren’t consistent with their expectations so I was construed as a malcontent – which, in truth, I was.”

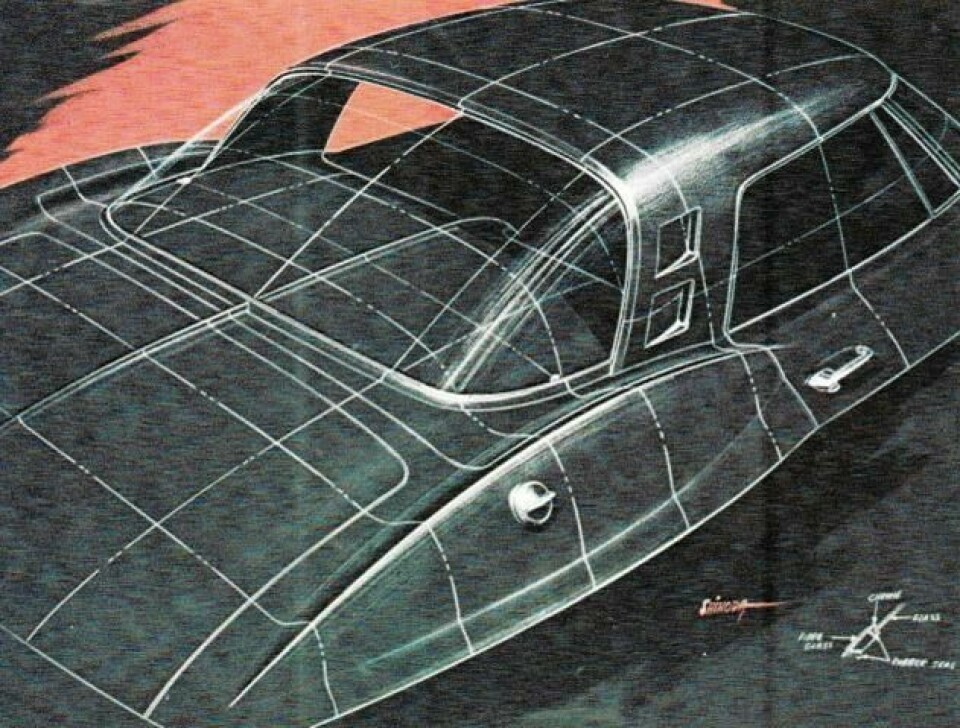

Larry Shinoda was an exceptionally gifted draughtsman. Note the contour lines describing the form on this Corvette sketch

Fortunately, an instructor had recognised his talent and had introduced him to a contact at Ford. Ford hired him and he stayed for a year, moved on to Packard, and then to GM – where Mitchell was waiting for that fateful race. Shinoda was pulled out of the Pontiac studio immediately and placed into the infamous Studio X, where Mitchell ran a number of stealth projects out of sight of GM management.

One of these was a racing car being built on a Corvette SS chassis donated by Zora Arkus-Duntov, the engineer who did as much as anyone could to make early Corvettes into race contenders. Mitchell’s self-financed project would eventually get a number designation, XP-87, and from an initial design by Peter Brock, Shinoda and Tony Lapine would develop the Corvette Stingray – an ultralight racing Corvette – completing the car in 1959. The Stingray, with its wickedly tuned engine and ultralight frame and body, would win the SCCA National Championship in 1960.

Bill Mitchell beside the Stingray racer concept and the first Corvette Mako Shark concept car

Mitchell then successfully lobbied for a further development of the car, this time with official GM money. Mitchell turned to Shinoda to transform the Stingray into a more street-friendly concept. He showed the young designer a mako shark he’d caught on a recent vacation and had mounted in his office. Mitchell wanted Shinoda to take the fearsome shark face and sleek form and find a way to translate that image on to the already sleek Stingray concept.

Mako Shark I concept – rear three-quarter view. Note Lexan top with periscope rear view mirror and custom blue/white colourway – a legend in itself

Shinoda was thrilled with the assignment and in 1961 his handiwork was first revealed to the public. Named, appropriately enough, Mako Shark, XP-755 was introduced to the public at the International Car Show in New York in 1961. There was an enormously positive response. The extended racing form of the Stingray was shortened a bit, but retained the blistered fenders and pointed rear end. A Lexan bubble top with a periscope rearview mirror was installed to give the Corvette a futuristic flair.

Mako Shark I concept – shown here with Mitchell’s trophy mako shark

The blue colourway with the white underbelly was particularly compelling to show goers, and had an interesting backstory. Mitchell has specified that the car should match the shark in its blue-to-white colours, and rejected multiple attempts by the painting crew to match his prize trophy. Finally, Shinoda sneaked into Mitchell’s office and borrowed the trophy, so the crew painted the shark to match the car. Apparently Mitchell never caught on to the trick. The story, true or not, became the stuff of GM legend.

The Corvair Monza GT concept previewed the Mako Shark II, and the C3 Corvette

Though the Mako Shark was enormously popular on the show circuit, there was no time for celebration. Mitchell had Shinoda working on a parallel program for a sports car based on the new Chevrolet Corvair (see last week’s story). But after a couple of nice custom Corvair Spyder concepts, Shinoda broke out a radical design for a mid-engined sports car with strong shark-like features. Mitchell asked that these design cues be transferred to a second Corvette concept that would extend the shark theme.

Mako Shark II with its older sibling Mako I. This is the fully running version with the massive 427 V8 engine

Work on the Mako Shark II began in 1964. The styling was derived from the Corvair Monza GT and also the Corvette XP819, a rear-engined prototype that Shinoda had designed along with engineer Frank Winchell as a proof-of-concept vehicle. Unlike the previous two cars, the Mako Shark II was a traditional front-engined car with a pointed nose and expressive flowing fender lines. The bubble top of Mako I was gone, replaced by a flat-roofed coupé form.

Mako Shark II – rear view. A bumper telescoped out of the rear fascia to protect the car. The louvres over the rear window assured that you couldn’t see a thing behind you, previewing the problems with the split window 1963 production car. The boat tail would re-appear on an early 1970s Buick Riviera

A boat-tailed fastback with a louvred cover made for a dramatic sweep across the rear of the car to the somewhat duck-tailed fascia. Two versions were created. The first, introduced at the New York show, was a non-running full-scale model with interesting styling cues and a radical interior. The second car, introduced in Paris, was a bit more subdued, but boasting a massive 427ci big-block engine, an experimental three-speed transmission and an interior that featured a vast array of electronic controls.

The Mako Shark II, with its dramatic side profile and infamous colourway

Both Mako Shark Concepts ended up being a glimpse into the future of the Corvette program. The Mako Shark I became the second generation Corvette, which debuted in 1963 with the controversial (and now classic) split rear window for the coupé. Although that only lasted one year, it was enough to turn the public’s view of the Corvette away from its first generation and towards the future. The second Mako Shark concept previewed the third generation of the Corvette, which would debut in 1967 as a 1968 model. The Mako Shark II would be mildly ‘remodelled’ into the Manta Ray concept of 1969, then retired to GM’s Heritage Collection in Detroit.

Larry Shinoda standing next to the Boss 302 Mustang

As for the principals in this story, they all went on to have distinguished careers. Bill Mitchell would remain GM’s design chief until 1977. His entire career would be spent at GM. Larry Shinoda would move on to Ford for a second time, and become the designer of the famous Boss 302 Mustang, before leaving to start his own independent practice. Peter Brock would move beyond the Corvette Stingray to work with Carroll Shelby then start his own racing program. He now lives outside of Las Vegas where he is a photojournalist and designer. Tony Lapine, who worked with Shinoda and Brock on both the Corvair Monza GT and the Stingray/Mako Shark programs, would eventually move on to Porsche, where he worked on both the 924 and 928.

The Mako Shark era, along with the mid-engined experiments and Corvair sports cars, were part of a wonderful period of automotive design, with colourful characters and an incredible legacy of concept and production cars. The work of those years would influence sports cars for a generation to come, and will perhaps even influence a new generation as alternative powertrains invite us to re-assess our perceptions of the sports car.