Design Essay: how adversity shapes cars

How have automotive designs responded to drastic shifts in society and culture in previous years? We take a timely look back

While an increasingly adversarial political climate, murmurs of recession and ever-mounting fears for our natural environment didn’t paint the rosiest of outlooks as we approached the third decade of the 21st century, the sudden onslaught of an invisible, insidious foe has turned wearying slog into waking nightmare for much of the globe.

In such testing and traumatic times, it’s perhaps tempting to dismiss discussion of the finer points of automotive design as little more than an exercise in self-indulgent futility or escapism. However, notwithstanding the possibility that a healthy dollop of the latter may be all that remains between many of us and insanity’s slippery slope, it’s interesting (and perhaps heartening) to note that the changing face of car design through difficult times is in fact a prime example of humanity’s remarkable adaptability and resilience – not to mention our collective mood.

Many periods in modern history have come to be defined just as much by their automotive output as by their music, fashion or art. Take the ‘roaring twenties’ for example (a decade invoked by Rolls-Royce’s latest collector special): a century on, what could be more iconic of a decade of unprecedented wealth, opulence and indeed decadence than the Duesenberg Model J?

Though nothing less than awe-inspiring in its depth of engineering, aesthetic majesty and sheer size, with hindsight it’s difficult not to view the ‘Duesy’, along with the Bugatti Royale, et al., as a somewhat chilling reminder of a society so intoxicated with its own (ultimately fleeting) success that it failed to anticipate or prepare for the inevitable darkening of skies ahead (sound familiar?).

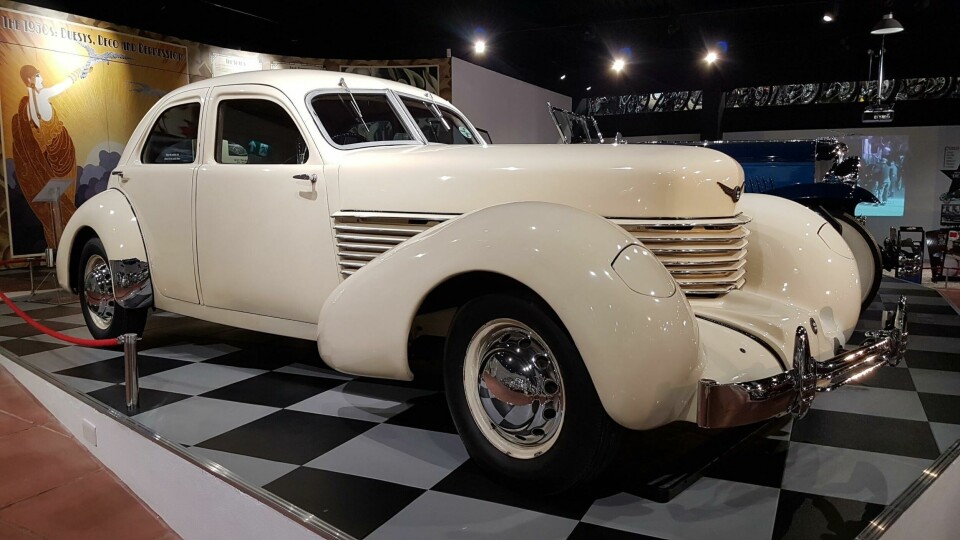

By contrast, the tone taken by the preeminent cars of the post-depression 1930s is strikingly different. The lower, more streamlined shapes of Citroën’s Traction Avant, Cord’s 810/812, Chrysler’s Airflow and Tatra’s streamliners, were perhaps indicative of a humbler, more cerebral approach to car design better suited to a world in a sombre, reflective mood.

Instead of attempting to impress with their extravagant size, cost and overbearing presence, these depression-era vehicles instead plumped for technological advancement as the bedrock of their appeal, with features such as front-wheel drive, monocoque construction and sleek shapes which worked in harmony with the laws of physics, rather than trying to beat them into submission as their forebears had done.

The aftermath of the Second World War brought even greater changes, as the now ubiquitous ‘ponton’ or ‘pontoon’ full-width styling template rapidly found favour.

Pioneered by Pininfarina’s Cistalia 202 and the Kaiser/Fraser sedan of 1946, such a bold step-change was surely befitting of a world perhaps keener than ever to embrace change, sweep away old orders and traditions and say ‘never again’ to the horrors of a then-recent past. Just as everything from empires to gender roles were reshaped in the post-war period, the new shape of ‘the car’ cast aside the last remnants of horse drawn carriages to truly become its own beast in a world keener than ever to embrace it.

Perhaps more than any other artefact, the car encapsulated the values, hopes and dreams of the new world: personal freedom, technological progress, social mobility and aspiration. As rationing faded away in the 1950s the relatively understated and austere Morris Minors and Ford Consuls of the immediate post-war era gave way to outlandish, space-inspired, fins ‘n’ chrome creations in a now rampant USA, while the continued experimentation of European manufacturers resulted in such seductive forms as the Mercedes-Benz Gullwing and BMW 507, alongside radical and innovative disruptors such as the Citroën DS, Fiat Nuova Cinquecento and BMC Mini.

But though it continued to blossom well into the 1960s, like all good things, the car’s honeymoon period couldn’t last forever. As the 1970s rolled around, oil shortages, US military humiliation in Vietnam and growing racial and class tensions in countries such as Britain and the United States dealt a dizzying blow to the collective confidence of the West – something which unsurprisingly was reflected in the utilitarian, prosaic, even downright timid, automotive creations of the era (Italian wedge concepts aside).

Many a macho muscle car found itself castrated – Ford’s 1973 Mustang II for instance, with its narrow track, gawky, upright body-shell and clumsy overhangs couldn’t have been further removed from the rugged, effortless cool of its 1960s predecessor. Pretty sports cars (Porsche 911, Alfa Romeo Spider, MGB) succumbed to ugly black plastic bumpers in the name of safety. Even the fashionable colours of the time, autumnal shades of brown, orange and beige, were distinctly downbeat.

Still, whilst many floundered, Italian masters Giugiaro and Gandini proved that more rational, straight-edged forms need not be unappealing, giving the world such clean-cut classics as the VW Golf, Lotus Esprit, Lamborghini Countach, BMW E12, Fiat Panda and Citroën BX, with the boxy, wedgy ‘folded-paper’ style – espoused by Giugiaro in particular – eventually coming to dominate both the 1970s and ‘80s.

Nevertheless, as the 1980s drew to a close, new storm clouds were gathering, for as the old saying goes, familiarity breeds contempt. True to form, the continued proliferation of the car throughout the (mostly) prosperous post-war decades had seen it accumulate a hefty rap-sheet of crimes against both humanity and the environment – and as the stock market crashed on Black Monday in 1987, the mood for car manufacturers began to sour.

Just as they had in the 1930s, engineers responded with a raft of new innovations; airbags, ABS and standardised crash testing (Euro NCAP) to name but a few. Not to be outdone and keen to ensure this more caring approach was communicated effectively, designers ushered in the soft, organic forms of ‘bio-design’ which would distinguish the cleaner, more responsible, fully house-trained cars of the 1990s from their uncouth ancestors.

Thankfully, the 1990s proved an infinitely more prosperous and upbeat decade than the 1930s, with the effective conclusion of the Cold War in 1991, dawning of the Information Age and rapid economic recovery combining to create a sense of light-hearted optimism which prompted designers to make hay whilst the sun shone. From Renault Twingo to Fiat Coupé, Ford Ka to Smart City Coupé, Toyota RAV4 to Volkswagen New Beetle, the 1990s was the period car design let its hair down.

What’s more, the psychological ‘blank slate’ offered by the dawning of a new millennium seemed to energise designers in the quest for next new thing, with what seemed like innovation after innovation hitting in the latter part of the decade – Ford’s radical ‘New Edge’ design language, the ultra-versatile packaging of Mercedes’ 1997 A-Class and the brightly-patterned interchangeable plastic patterns of the aforementioned Smart to name but a few.

Alas, as the nineties’ playful optimism and sunny outlook was swept away in the rubble of New York’s Twin Towers, car design began to lose its edge. Where once there had been razor-sharp bravery (Focus), icy-cool chic (TT) and otherworldly wonder (Multipla), by the mid-noughties there remained only bloated blandness.

Furthermore, even the variety of genres on offer began to suffer, as coupés, roadsters, MPVs, even mainstream hatches and saloons (sedans) ceded ground to all-consuming SUV trend. That post-9/11 paranoia should have given rise to such vehicles is perhaps not surprising; their imposing facades, ‘commanding’ seating positions and (in some cases) quasi-military overtones were perhaps well-suited to a world increasingly watching its own back.

Even so, design innovation and inspiration continued to brighten the malaise of the 2010s, with BMW’s visionary i3 and i8, Mazda’s latest back-to-basics MX-5, Honda’s delightful E and Porsche’s forward-looking Taycan being just some of those to have brought a little sunshine to a decidedly overcast decade.

But how exactly is any of this relevant today?

Well perhaps, as a post-credit-crunch, post-Brexit, post-Trump world finds itself in the eye of a new storm, one in which the winds of change seem to be to howling perhaps more loudly than ever, maybe, just maybe, us creative types can look to the past for inspiration.

Though it’s clearly far too early to begin counting the true cost of COVID-19, let alone imagining how a post-pandemic world may look or feel, hindsight teaches us that it’s often when faced with what seem like overwhelming odds that designers and creatives – as indeed humanity itself – are most wont to truly excel.

It’s that thought which can perhaps provide a modicum of comfort in even the darkest of times. For while design may not always be able to cure the sick or rebuild shattered lives, it can, does, and will no-doubt continue to illustrate humanity’s astounding ability to overcome adversity, shape our surroundings and work towards a better world in the long term – and that’s something we should all aspire to, now more than ever.