First Sight: Tourbillon is a Bugatti to watch

Design director Frank Heyl explains the all-new Bugatti

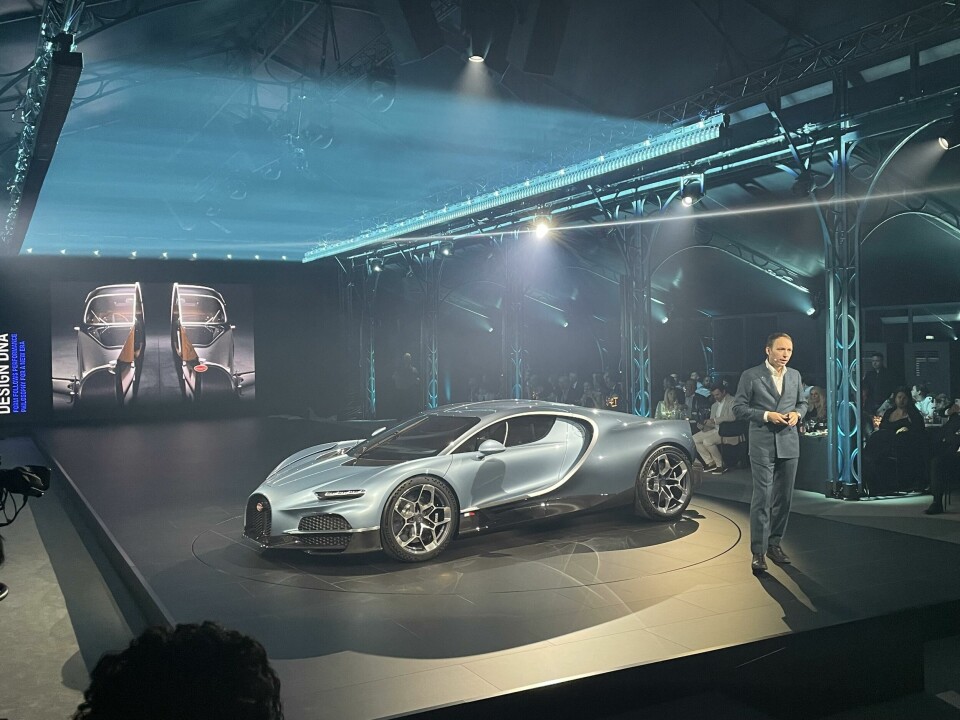

As world premieres go, the unveil of the all-new 1800hp V16 hybrid Bugatti Tourbillon hypercar on a balmy night on June 20th, at the home of the esteemed French car brand in Molsheim, was a pretty big one.

Suitably suited and booted, Car Design News had a ticket to ride, but chose to sashay straight past the Ultra High Net Worth Individual guests to snare an interview with the enthusiastic and knowledgeable Bugatti design director Frank Heyl.

To be fair, before that, we did also quaff a little champagne poured by a pair of waiters manhandling a giant-sized bottle about the size of three baseball bats stuck together – possibly a 15-litre Nebuchadnezzar or even an 18-litre Solomon – and had a short mosey around the marque’s expansive grounds to clock a diverse array of Bugattis spanning a century-plus of luxury and performance design.

From the incredibly long-nosed and wonderful swoopy, straight 8-cylinder late-1920s Type 41 Royale Coupé de Ville Binder, to the early-2020s low-slung, matt-black Batmobile-esque track day-only Bollide, the collection was truly jaw-dropping – and a real and rare treat to see in the metal (and carbon composite).

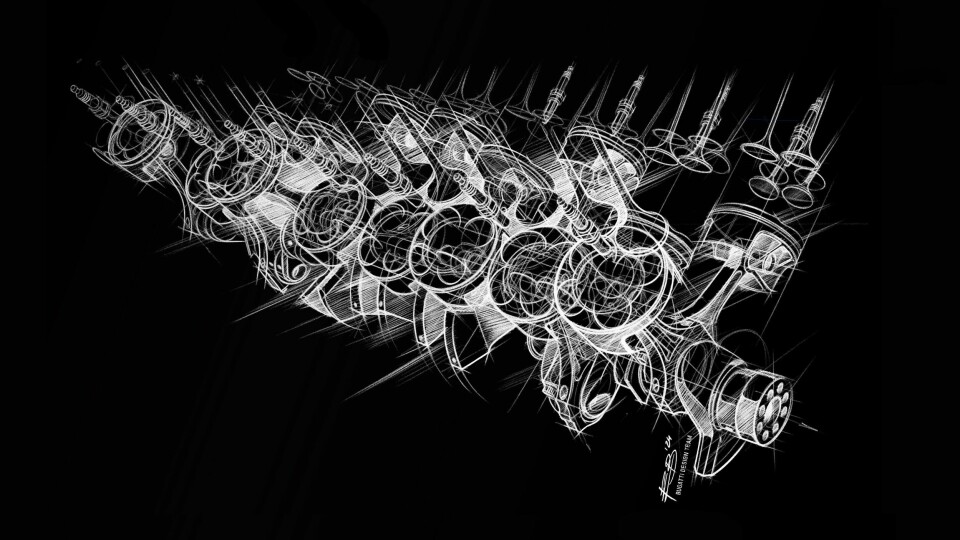

But the star of the show was the Tourbillon, a £3.2m ($4.1m) hypercar. As the first all-new Bugatti since EV specialists Rimac took control of the brand, it could have been an all-electric affair, but owner Mate Rimac had other ideas, as he declared on the night: “The obvious thing would have been to re-skin a Nevera, but Bugatti doesn’t do obvious.” Instead the Tourbillon boasts a Cosworth-developed 8.3-litre V16 petrol engine and three electric motors – two at the front and one at the rear – able to catapult the car to 62mph from a standstill in 2.0 seconds but also offering 37 miles of pure electric range.

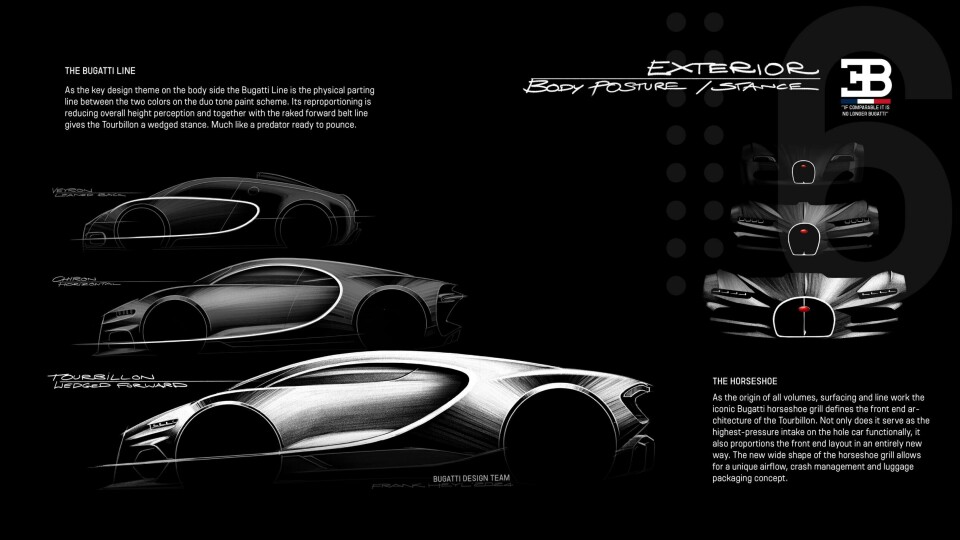

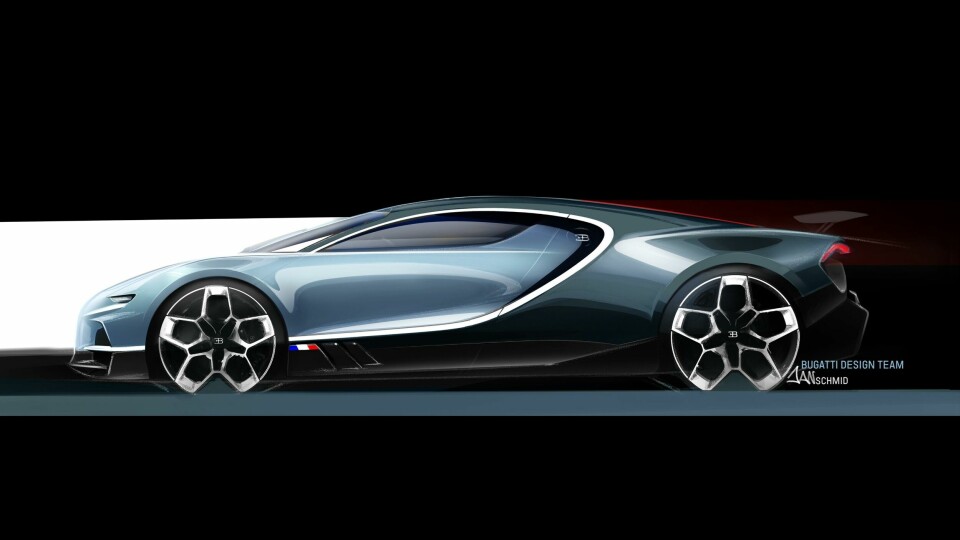

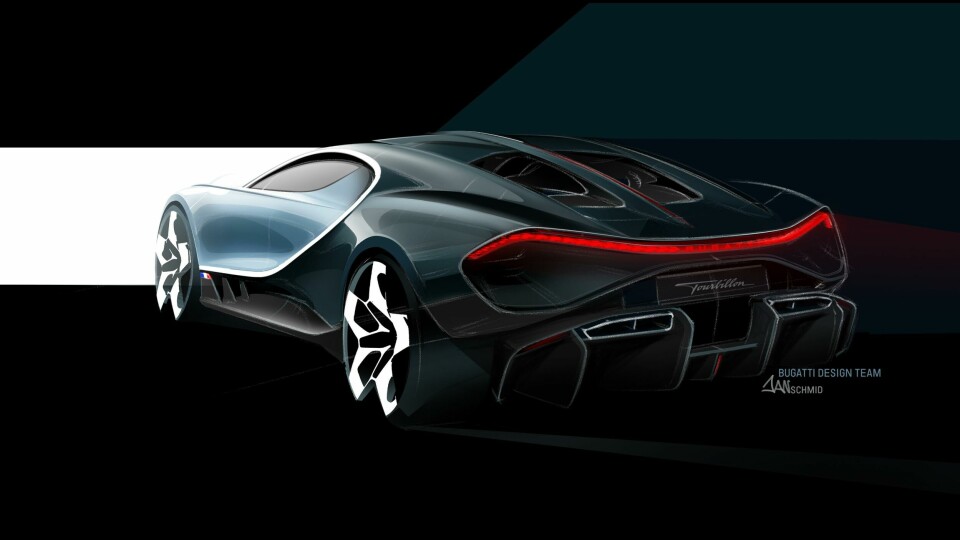

Only 250 units will be made and the Tourbillon’s job is to replace the Chiron. That’s a tough gig, as the Chiron is arguably the most elegant Bugatti made this century and combines beauty as well as brawn, in a way its Veyron predecessor never quite managed. The Tourbillon has clear references to both and is an evolution in terms of exterior design, but channels some elements from the later Bugatti limited editions, including the one-of-one La Voiture Noire’s more complex front and rear ends.

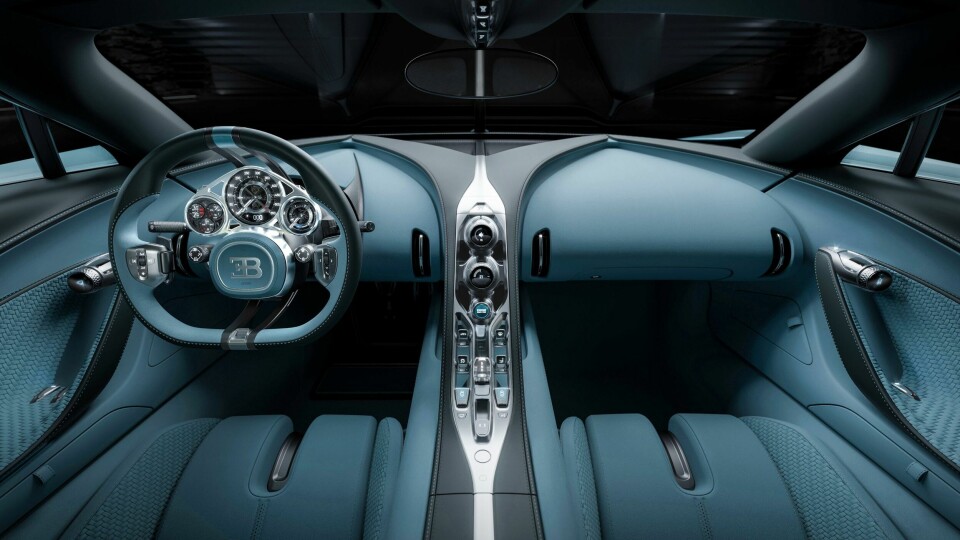

Arguably the show-stopping detail of this showstopper is within the interior, in particular the driver display cluster, resembling a trio of giant-sized skeleton watches and a logical reason for the car’s name, after the famously complicated and expensive mechanical watch balancing device beloved of ultra high-end watchmakers to improve accuracy at all angles of use.

Keen to find out more, CDN caught up with Heyl to talk analogue design versus a digital design process, diffuser patents that make him proud and the importance of design longevity…

This car is an analogue product, from the driver display to the petrol-hybrid engine, but you used VR to design the Tourbillon. Why?

Because it’s so expensive to have a clay model running and so slow. I’m a digital native in terms of modelling and I’m used to reviewing cars on-screen.

But at some point did you make 1:1 full-scale clay?

Yes, you have to, especially for the interior, due to the ergonomics and how you feel in the car. But it’s not like we spent months and months refining a clay model. We don’t have the money for that.

When did you start the project?

We started in the second half of 2021 and signed off ‘the surface freeze’ in February 2024.

Was the interior and exterior done in tandem, or one ahead of the other?

The exterior design led and the interior design tailed about three months behind it.

How long did it take before you decided to go for this very analogue watch-inspired driver display? The exterior is an evolution – as Mate Rimac said, but the interior seems a bigger change?

If you look at a Type 35, it is celebrating its 100th anniversary this year. And it’s not just been forgotten about, its being entered into historic races and still enjoyed by vehicle connoisseurs around the world. Once built and hopefully never crashed, these things don’t disappear.

They endure the decades in these collections. So what does that mean for design? It means it bloody better be timeless and not littered with today’s technology. If you get into a car made ten years ago and fiddle around with the navigation system and screen, it’s a rather miserable experience. Fast-forward another 90 years and will we have augmented reality implants? Or holographic displays? Who knows? So we chose the Tourbillon, like a mechanical watch, to be timeless.

Who’s decision was it to have this watch-style driver display?

We were pushing the agenda but it resonated within the company. Mate [Rimac] is fully on board with these things and if you have a good argument he’s like, ‘Let’s do it’. It doesn’t go into a drawer or through ten committees to then think about for a year.

Mate Rimac also said the new car could have been full-electric, did you propose quite different sketches based on that possibility?

No, it was pretty clear, very quickly that the next Bugatti would have to have an internal combustion engine.

Is that because the collector market is not yet fully respecting EVs?

No, I disagree with that. There is certainly a niche, for electric high-performance cars that accelerate [to 62mph] in under two seconds and can do things that internal combustion engines cannot. In terms of digital torque vectoring, full revolution control of each individual wheel means you can do many things that are absolutely amazing with electric powertrains. That’s why we built the Rimac Nevera. I’m also director of design for Rimac.

What happened when Rimac took over Bugatti? Was there an existing Rimac design team?

We joined forces. We have 50 people in design now, roughly split between ten exterior, ten interior, ten colour and trim, ten CAD modellers, five graphic designers and five UX designers.

Given how watch-inspired the driver display is, did you have to have to seek outside help to create it?

We did send out our interior designers to Geneva, as it’s the epicentre of watchmaking, and they did educate themselves on the art of watchmaking. And there is a lot to learn. These vehicles cost €3m-plus each, so as a designer you might not have access to such cars, so what I regularly do with the team is check out collectors’ garages to see what cars are in those collections and how the people that own them experience them. Only through this can we get new ideas.

Which period of Bugatti design history is your favourite?

Right now, as we are at the height of our game. I’ve been with this brand for 16 years and my first project was the Veyron Super Sport with 1200hp and 431km/h. I was more junior then, standing by the racing track when our test driver drove past in my car – the car I designed – and my trousers went like this [he motions a sudden movement in their crease] and thought, ‘this is what I want to be doing’.

Was that straight from college?

I studied at the Royal College of Art in London, then I went to Skoda for two years then I got a call [Bugatti and Skoda were both in the same VW Group at that time]. I also worked for Volkswagen and Audi.

Anything you’d put your name to - whether concept or production?

I designed the Skoda Rapide, an entry-level four-door car for €30,500 and I was fighting with the ‘bean counters’ for 50 cents per wheel bearing to get a good offset and stance for the car. I lost.

So it’s different now at Bugatti.

[Smiles] It is a little different now.

Despite a much bigger price point at Bugatti, are there still moments when senior management says ‘No’?

From the outside it might look like this is NASA – with somebody saying, ‘Go to the Moon, no matter what it cost’. But that’s not how it is. All these projects – imagine you only do 85 cars per year – it’s a very limited number of units to cover your investment. So you can imagine all these cars’ business cases are calculated with a very sharp pencil. How we still make ‘the impossible possible’ and continue the business case, gives us all a job.

Which part of the Tourbillon design are you most proud of in production?

[Without a moment’s hesitation] The diffuser. I personally hold a patent on the diffuser and its crash concept. It was my idea, and I still can’t believe it’s on the car.

So what’s different about it, compared to others?

Any normal car at the rear has a metal crash beam for legislation to pass worldwide. This diffuser has four vertical fins that have carbon fibre crash structures in them that will collapse like a Formula 1 nose cone. They are built up in several different layers and thicknesses so that the more you crush it the more kinetic energy it will absorb. Through that I was able to pull the diffuser [up] as high as your knee. This is unheard of in a passenger road-legal car.

So was that height for aesthetic reasons?

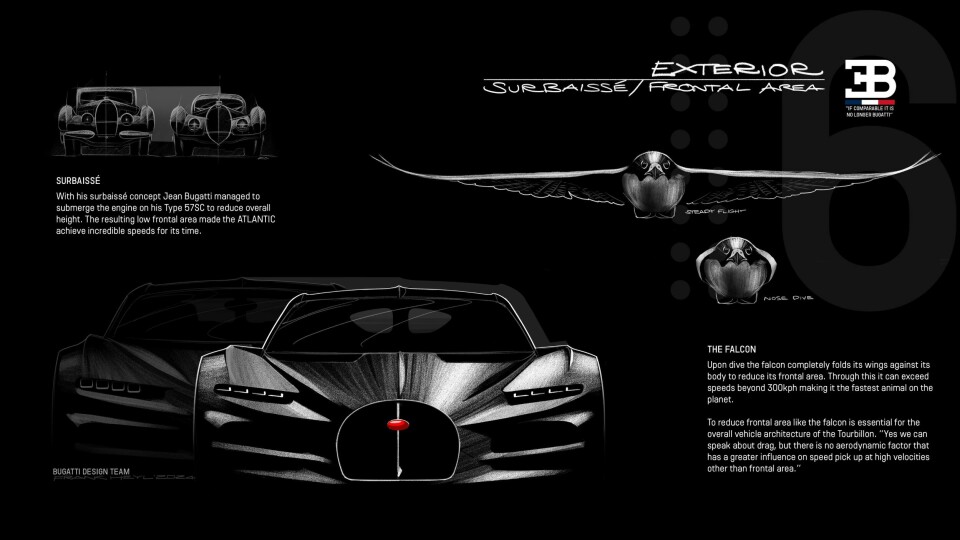

That was a takeaway from 16 years of designing high-speed cars. Cars that go over 400km/h need to establish an aero balance. At 400km/h you neither have ‘lift’ nor downforce. You don’t want downforce at that speed, because it will overload the tyres, and tyres are the critical elements at that speed. The car wants to lift off – most aircraft have taken off at 250km/h – so the car wants to take off. You need to cancel out enough lift with the downforce with a base shape of the car that is aerodynamically efficient.

So it’s about creating aero balance without using – and this is key – a wing. So we created the diffuser, which in side view is a ‘drop’ shape, a wing profile angled in the right way, so the base shape of the car creates the downforce.

Did you study engineering as well as design to know all about this?

No, I’m self-taught. Sixteen years of doing high-speed programmes teaches you something.

What do you drive yourself?

A Porsche 911 GT3. Last weekend I was in Spa in Belgium, my favourite racetrack. My favourite game is me against the clock, ideally on an empty track.

Away from cars, what other design influences are important to you?

Architecture, especially Lautner and Calatrava. And also fashion. I like to say this is ‘car couture’.