Flashback: Four fibreglass pioneers of the car world

Often derided as “a poor man’s carbon fibre”, fibreglass was critical in the development of the modern sports car. We take a look back to the beginnings of the composites era

In America, leisure boats and sports cars exist, in their modern form, because of one material: fiberglass. An overstatement? Perhaps, but not by much. Bear with us as we recall a little history.

Fiberglass is one of those materials that evolved rather than invented at fixed point in time, like the light bulb or telephone. In the 1930s, glass fibers were increasingly spun into thinner and stronger threads by intense mechanical processes. Large corporations like Owen-Illinois and Corning Glass were looking to somehow weave these fibers into a cloth like cotton or wool, and then looking for a product to create from it.

Reinforcement, resins and the glass itself were tricky materials to handle, and combining them all into a workable cloth was an obsession of both big industry and small garage-based inventors – mostly boatbuilders – who saw the potential for fiberglass cloth as a hull material.

The first fiberglass car was designed by William Bushnell Stout, who in the 1920s developed the Ford Trimotor and in the 1930s designed and marketed the radical Stout Scarab. In 1946, the indefatigable Stout, in partnership with Owens-Corning, developed a fiberglass car, called the “Project Y”, which he promised would revolutionise the industry. It didn’t, but it put fiberglass on the radar of auto manufacturers. It also began important conversations about the role of “composites” in automotive design and manufacture.

But in 1946, the automobile industry was converting back from wartime production, and getting product to market was paramount. Many 1946 and 1947 designs were mildly re-styled pre-war cars. Innovation was a secondary concern at best.

On both coasts, however, fiberglass was making huge inroads into boat manufacture. The material had come a long way during the war, and new fiberglass models were in the proof-of-concept stage, or already fully developed. Navy contracts were still being let to boat builders, and the new material began to move from an experimental and military use to everyday civilian craft.

Some of these new boat builders saw the potential for fiberglass to be used in cars. In magazines at the time there were breathless predictions about fiberglass and plastics changing home building, boats, cars and airplanes, an entirely new landscape based on civilian uses of wartime technology.

In Costa Mesa, California, a few boat builders began experimenting with fiberglass in auto bodies. These were boat guys, so they concentrated on bodies rather than trying to engineer an entire car. One of these was William (Bill) Tritt, who was experimenting and pioneering fiberglass in various marine uses, from hull restoration to entire boats-usually small craft.

Boatbuilders and hot rodders dropped by Bill’s shop on Industrial Way to shoot the breeze and check on the progress of his creations. One of these was Ken Brooks, a friend who had stripped down a 1940 Willis and was looking for a body for his new hot rod. Tritt suggested fiberglass, a material he had argued was perfect for car bodies.

Brooks agreed to his proposal, and within months a body had been laid up using techniques Tritt had pioneered in boatbuilding. The overall styling was based on Tritt’s favourite car, the Jaguar XK120.

The finished car, a curvaceous two-seater, was shown at the 1951 Petersen Motorama in Los Angeles, along with other experimental roadsters with evocative names like Skorpion, Wildfire, and Wasp. Most built on the same street as Tritt’s shop, an incredible concentration of automotive, marine, and in particular, fiberglass, experimentation and talent.

Tritt’s car got enormous publicity and he incorporated his business, naming it Glasspar, making both boats and fiberglass shells- with or without a chassis underneath. It was the beginning of the kit car craze in California and seemingly, the opening salvo in a revolution in car design and construction.

At the same time, just down the street on Industrial Way, Tritt’s friend Eric Irwin also had a shop repairing boats, and was an accomplished woodworker. He, like others nearby, was fascinated with Tritt’s work in fiberglass.

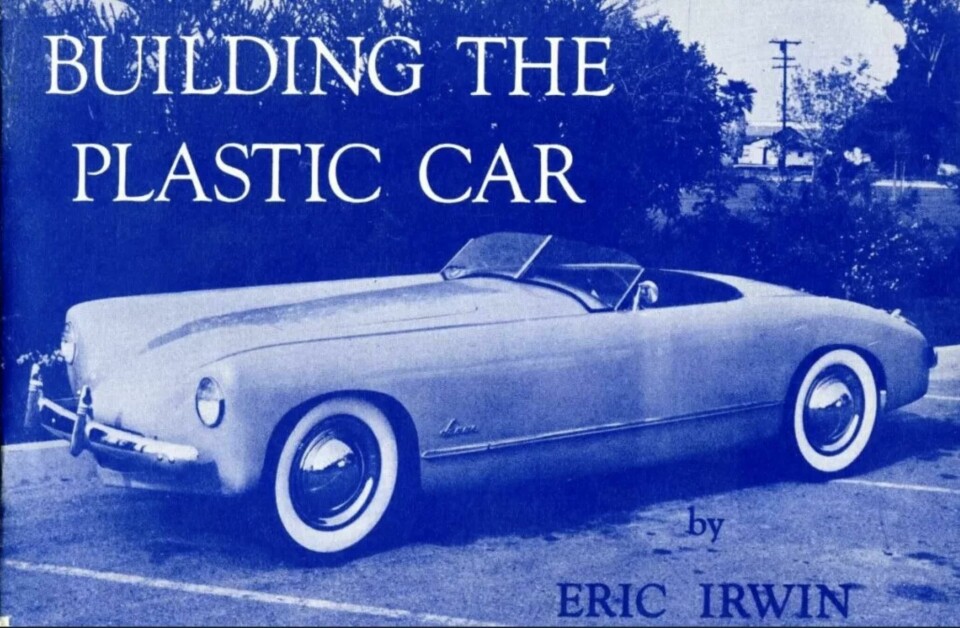

He would build his own fiberglass car, which was actually completed just weeks before Bill Tritt’s car. Named the Lancer, it too was a roadster, but with less body sculpting and a long hood (2,200mm!). It was good bit larger than Tritt’s with a 1932 Graham chassis and a Studebaker Champion engine, but equally daring in concept, and equally popular at the Motorama.

Irwin was already producing and marketing versions of the Lancer by the end of 1951, again, slightly ahead of Tritt. Additionally, Irwin would write the first article, published in Motor Trend in 1952, about building a “plastic” car. He also wrote a book about his techniques for the DIY crowd, optimistically assuming they could get fiberglass in any quantity – this during a time of shortages due to the Korean War.

Meanwhile, Harley Earl, the legendary VP of design at General Motors, heard about the California fiberglass projects and quietly visited both Tritt and Irwin in their workshops. Earl had noticed young people buying European sports cars and sensed a trend. He even imported a new MG for his new daughter-in-law. Earl was interested in creating an American sports car, something young customers could buy from an American automaker – namely, GM.

Earl soon hired Tritt as a consultant, who made several “stealth” trips to Detroit to advise Earl and his team on their secret sports car project called “Project Opel”. The influence and know-how of experimenting boat builders, hot rodders and sports car fanatics soon found a home in the world’s largest automaker.

“Project Opel” would be fully developed during 1952 and introduced at the GM Motorama in January 1953. The little sports car was an instant hit with enthusiasts, even though it had an anemic engine, no side windows and a body that leaked like a sieve. But the fiberglass spoke of the future, and its size and styling reminded many of European sports cars.

The car was even given a nautical name, one that suggested sleekness, speed and maneuverability, a name now legendary in the annals of American automotive history. That car? The Chevrolet Corvette.