Generations: looking back at the Dodge Charger

A look back of the history of the Dodge Charger reveals the good, the bad, and the plain awful

The Charger was born out of a desire of Dodge dealers for their own pony car to compete with the Ford Mustang.

Plymouth already had one, the Barracuda, and Dodge dealers felt they were shortchanged by Chrysler management. The result was the Charger, which was originally positioned between the Barracuda and the Ford Thunderbird, meaning it was an uncomfortable combination of pony car and personal luxury car.

The original Charger was designed by Carl ‘Cam’ Cameron. Cameron sketched a fastback for the Coronet-based coupe, the “electric razor” grille, the hidden headlights, and the innovative interior, which featured a console that ran from back to front and rear seats that folded to make an enormous trunk space.

The fastback idea was a throwback to the 1940s era of cars with their streamlined shapes. Carl Cameron would later recall, “I always liked the ’49 Cadillac fastbacks and so I drew up a fastback. And it was a big one!”

The first-generation Charger of 1966-1967 was a mid-size coupe based on the Coronet. It was more of a personal luxury car than a pony car – too large, and too much like the Coronet, and though handsome, did not sell well. It was compared with, and did look like, the AMC Marlin, another not-quite-pony car with more personal luxury touches.

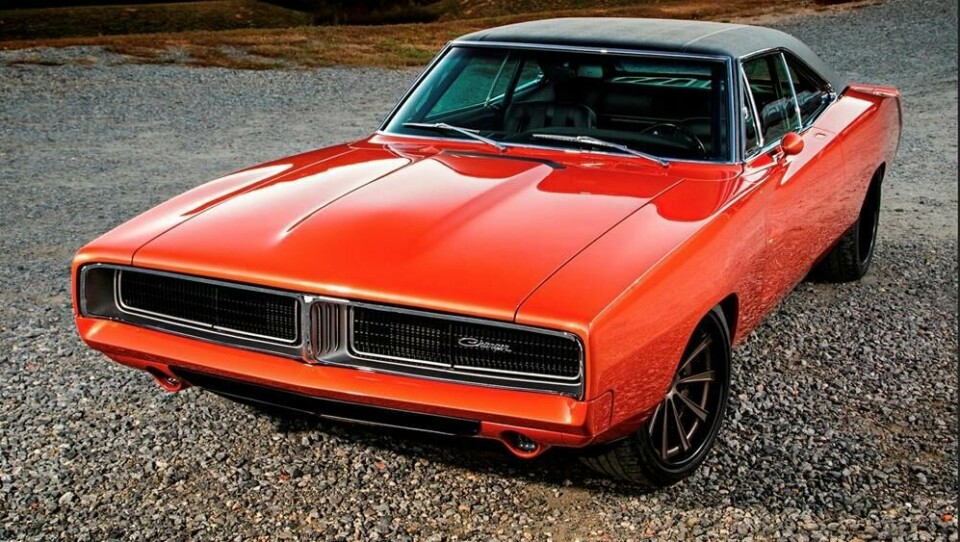

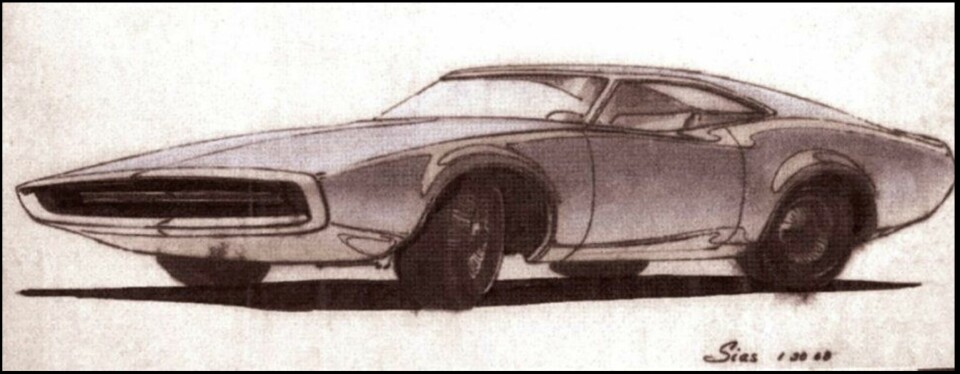

The second generation moved away from the Coronet in terms of style and appearance, though they shared the same underpinnings. Designed by Richard Sias, it employed Elwood Engel’s signature “fuselage styling”, which emphasised a purity of form, taut surfaces, and minimum of chrome and ornamentation.

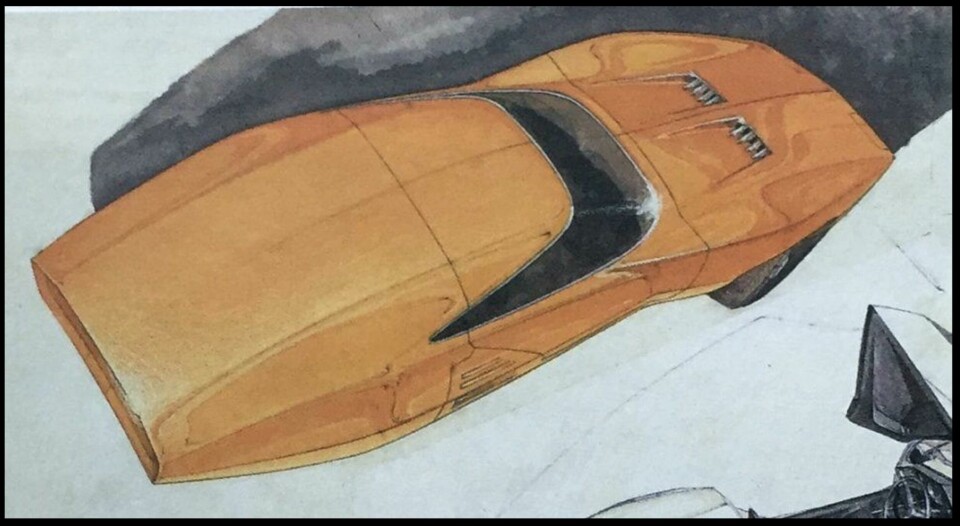

The design emerged from a simple, but compelling design sketch, that, at his managers’ encouragement became a series of renderings and then a clay model. Initially it was just a design study, a rendering of a futuristic coupe with overlapped diamond-shaped masses.

“The 1/10 scale model was purely a fun thing on the side,” Sias later recalled. “But people were beginning to take notice of the unique plan view shape. No matter how I worked it, I kept coming back to the double-diamond shape intersecting at the base of the windshield.”

The little model became more and more defined and Sias’ managers assigned a couple of full-time modellers to the project to develop it further. Bill Brownlie, chief designer at Dodge, was not enamoured with the study and wanted an evolution of Cameron’s first generation.

But fate intervened, when, as Sias recalled, “Engel walked into the studio, slapped Brownlie on the back and said, “That’s what a real car should look like.”

To punctuate his approval, Engel brought in the entire Plymouth studio to review the in-progress model. Brownlie fumed, but the second-generation Charger was born.

The design of the 1968-1970 Charger would become the one most fondly remembered by enthusiasts, and for many hardcore fans, the only Charger worthy of the name. This was not only a very popular generation of Dodge’s muscle car, but also the one to become a movie and TV star, with prominent roles in the movie Bullitt, and the TV series The Dukes of Hazzard.

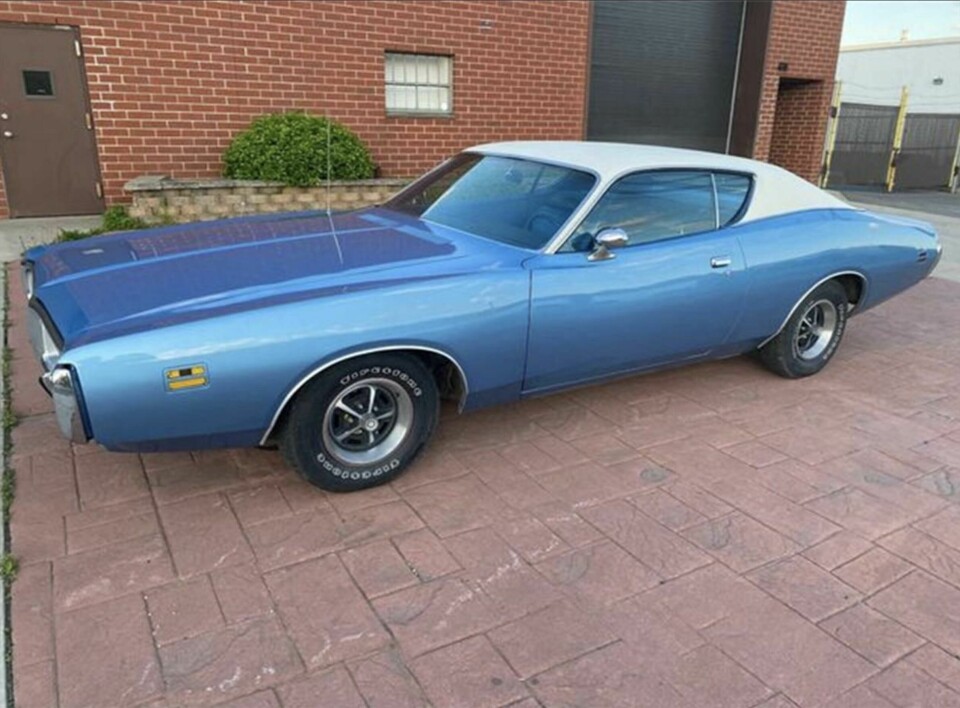

The third generation Charger of 1971-1974 was similar in shape, but with more pronounced “Coke-bottle” massing. Richard Sias drew some of the initial design sketches, but his colleagues Darin Yazedian and Harvey Winn completed the design under Bill Brownlie’s supervision (Sias left for Teague in 1968, disillusioned with the automobile business).

The new generation had a shorter wheelbase, and benefitted from the Coronet dropping its two-door variant, thus pushing buyers toward the Charger. Sales reached a high for the nameplate in 1973 with over 100,000 units sold.

But both Dodge engineers and customers saw the writing on the wall: the Hemi engine was retired, emissions equipment regulations loomed, the price of fuel spiked, and the high cost of insurance were beginning to weigh heavily on performance cars of all kinds, and the future looked very constrained indeed.

The fourth generation of the Charger was a pivot-point for the nameplate, as the performance car image was set aside for a personal luxury car position in the market. The Charger shared underpinnings with the Chrysler Cordoba, as Chrysler desperately tried to catch up in the race for an iconic personal luxury coupe.

It was a disaster. The Cordoba found great success with 150,000 units sold the first year, but the Charger already had an established performance image and the about-face turned off the buying public. Its sales were 1/5 that of the Cordoba. As one potential customer put it, “I see the Charger nameplate, but that’s no Charger.”

By 1978 the Charger was gone.

Burton Bouwkamp, one of the product planners for the Charger programme, would later recall: “I can’t escape the fact that I was director of product planning and was part of the fateful 1975 decision that sent the Charger on a path to oblivion.”

The Charger would return in a radically new form in 1981, as Chrysler modified its “L” platform from the European Simca for a small “hot hatch” Charger. The less said about it the better.

Indeed, we couldn’t find any designers to quote, as, apparently, few were willing to speak about it. As for customers, Charger purists were appalled by its small size, Volkswagen (!) engine (soon a Chrysler/Peugeot one), front wheel drive, and econobox looks.

Chrysler would stick with the fifth generation until 1987, even retaining Carroll Shelby to bring some performance to the car, but to little avail.

During the 1990s, the Charger languished in the shadows as Chrysler moved on to other projects.

Then Chrysler brought the Charger back in 2005, placing it on its LX platform which shared many parts with Mercedes cars of the era. And the car debuted with four doors for the first time – a shock to Charger purists.

Jeff Gale, a senior designer at Chrysler (he is still there), along with Ralph Gilles, Mark Hall and Michael Castiglione, explained the move to a four-door format. “Back in the 1960s and even the 1970s, two-doors made up probably 75 percent of the market,” Gale said. “Today, two-doors are maybe 20 percent. We simply didn’t see the benefit.”

Richard Sias, designer of the second-generation Charger, was not exactly a fan.

“I’d love to have, from the A-post forward, a do-over,” he said. “From the centre line and the front wheels forward, it doesn’t say ‘Charger.’” But he said the rest of the design stays true to the essence of his vision. “That’s tough to pull off,” he conceded. “That’s harder than doing the original car almost.”

In 2011 Chrysler was ready for a new generation of Chargers, but one that that kept the four-door format while employing some styling features of the second-generation models. It was longer and lower than the previous generation, with a smoother, flowing shoulder line and a more rakish windscreen.

In 2015, Dodge would implement a substantial makeover, one that employed a new front mask with LED headlights and a narrower grille, more sculpted, but with a trimmer “Coke-bottle” styling and totally reworked interior. Engine power and capacity would dramatically expand with Hellcat and widebody options emphasising speed and power.

And, now in 2024, Dodge returns the Charger to market as an electric car, one totally performance driven (ICE options will be available). The car will initially be made in a two-door format, the first since 1987. Four-door versions will follow. But Dodge is clearly evoking the second-generation Charger, the North Star of all Charger designs.

Says Ralph Gilles, director of design, “The ‘68 embodies so many fascinating details and amplifies the Dodge ethos perfectly… We still use it as a spiritual reference to this day as we design the next generation of performance cars.”