A new design language for Maserati

Goodwood interview: Klaus Busse on the MCPura

Car Design News caught up with Maserati design supremo Klaus Busse to talk about the MCPura, design tools and why he is looking to the 1950s for inspiration

Car Design News: What's the story, Klaus?

Klaus Busse: So, the big news about this car is how we're evolving the face of Maserati. We actually started this journey two years ago with the MCXtrema, which is a track-only car.

CDN: The Beast of Modena.

KB: Exactly. We knew we wanted to have some fun and experiment with a different design vocabulary. One of the many things the Xtrema gave us — aside from the trident-shaped tail lights, for example — was a reinterpretation of the front.

So you can still see on the MCXtrema this kind of oval grille, but it’s more of a second read, much more horizontal. Then, last year, when we launched the GT2 Stradale, we applied that more horizontal grille again. This is now the third iteration of that phase. You can still read our classic oval grille, but now it's interrupted by an upper section so it's a much more horizontal face. It's another evolution of the Maserati face, which I felt was necessary. We've been in the world of the oval grille for 20–25 years now, certainly since 1998 with the 3200 GT.

KB: So, it was just time, after 20 years, to take a significant step forward. That was the main reason behind this car.

CDN: It is much more planted.

KB: If you focus on the oval, it puts everything at the centre. That's what our cars had in the past too — even in the '50s. It was very Maserati. But your observation is spot on. I thought, let’s really make the car a bit wider and let it breathe.

The reason we don’t have a rear wing is because we don’t need one. The whole surface is designed to be the wing.

The reason we don’t have a rear wing is because we don’t need one. The whole surface is designed to be the wing.

CDN: Can you walk through some of the details?

KB: So, we did a couple of new things around the car. The wheels have these double X patterns. Normally, our wheels are trident-inspired. But I felt we had locked ourselves into the three-spoke world too much. For this new generation, I wanted something that played with the multi-spoke designs of the A6GCS cars from the '50s but with a modern take. So we came up with this double X. You still have the three-spoke trident we use on all our cars. But then you put the double X in there as a kind of homage to those wire-spoke wheels.

CDN: Why the '50s? Why are you looking to that era right now?

KB: Because the A6GCS, for me, is still the mental hero car. It taught me a lot about how we want to design Maseratis. In 1954, when they made the A6GCS, they basically took a Formula One car — just a central fuselage — and added bodywork to cover the wheels for road legality.

That created this dramatic topography. What we took from that is not a retro design element, but the concept of constructing the car around a central fuselage, with pronounced wheel flares that intersect and create interesting surfaces and reflections. That lets us avoid putting unnecessary lines or edges on the car. It all comes from the intersection of volumes — from the wheel and body. That concept really comes from the 1954 A6GCS.

CDN: Tell me a bit more about your use of negative space.

KB: We respect the way we construct the car’s main surfaces. That means a central fuselage that emerges from the grille, wraps around the canopy, and flows to the rear. We have that on all our cars. That inspiration comes directly from that racing-to-road era.

It’s important because our brand philosophy is "Gran Turismo." Not just the name of a car — but the idea. It's about combining the racetrack with the road. And we always want to echo our racing roots with those fuselage shapes. Now, on the GranTurismo, we went high with the volumes. But on this car, we didn’t because we're using the full body of the car as the wing. The reason we don’t have a rear wing is because we don’t need one. The whole surface is designed to be the wing.

We worked on the Italian Pavilion at Expo Dubai, and the slogan we created was “Beauty connects people.” I think that’s Maserati’s role, to bring people together through beauty.

KB: It’s a flatter section here [points to the wheel arch], rather than round because it's used for downforce. So if I want to go up here, I need to create space there. And by pulling air through, we can create something that’s not just a cliché but makes aerodynamic sense. Using negative space gives us balance and a dramatic look. We worked on the Italian Pavilion at Expo Dubai, and the slogan we created was “Beauty connects people.” I think that’s Maserati’s role, to bring people together through beauty.

CDN: How much of that fuselage design came from the tools people were using back then?

KB: Totally, you can see how the cars were modelled. Post-war, it was like aircraft construction: a wooden frame, then hammered aluminium over it. That defined the car shapes of the late ’40s and ’50s. Then in the ’60s, something important happened: side windows became curved. In the ’50s, they were flat, so the body needed shoulders. With curved glass, you could sink the windows into the body so flat sections like on the Ghibli became possible.

Then came the ’70s: engines went to the back, and we had more plastic fascias. Every time the cars changed, it was driven not just by designers, but by technology, society, and tools. Even the 3200 GT interior shows vellum-paper design with soft shapes, airbrushed effects. Each decade had a different medium: drafting in the ’50s, Canson paper in the ’60s, vellum in the ’80s. You can see those transitions in the cars.

CDN: So what about the moment we're in now?

KB: This current generation is society-driven. Growing up in Germany and living in Northern Europe, the role of the supercar has been critically debated over the last five years. So it was important for me to create something that, wherever you go, people respect it, not something ostentatious or cliché. We worked on the Italian Pavilion at Expo Dubai, and the slogan we created was “Beauty connects people.” I think that’s Maserati’s role, to bring people together through beauty.

CDN: Tell me about the colour and finish.

KB: With this car, we stayed within the blue world because blue is Maserati but I don’t like always using the same blue. That’s not very Italian. So we explored the water theme: Aqua, Nettuno, the Trident. We found a pigment that flops in the light. This morning, we had the car in full sun for the reveal. It shows off best that way.

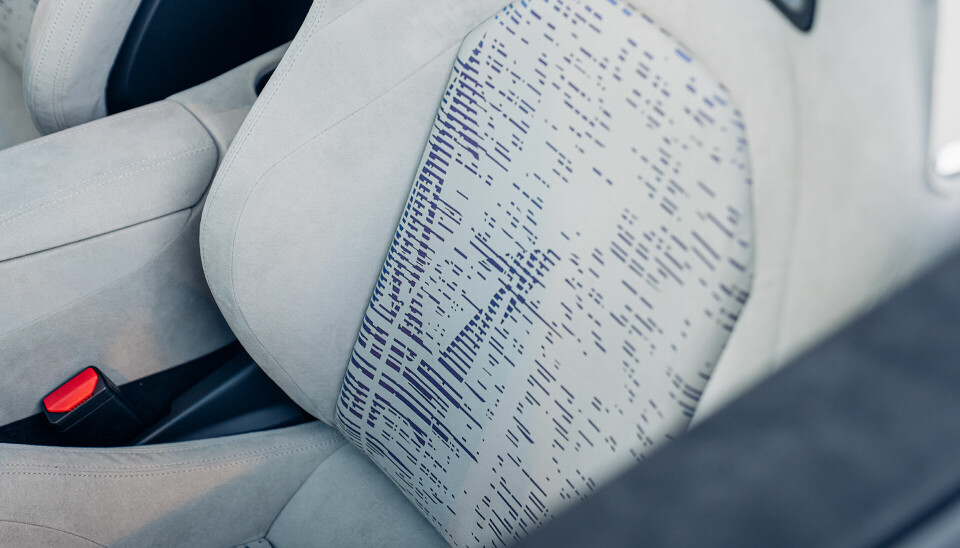

CDN: You have also done something quite interesting with colour in the interior.

KB: We originally did this laser-etching detail for our electric cars, and we’re now bringing it to ICE cars. As far as I know, we’re still unique in the market. We program a laser to etch a pattern, then fuse a second, metallic-blue fabric underneath to give this glowing effect especially when hit by sunlight. Again, I like to highlight it because people think Maserati means only wood or carbon fibre. But our DNA includes “when science creates art.” We use lasers not just for precision, but creatively. Others might laser in straight lines but we like curves.

CDN: That connects to your earlier point about design being downstream of technology.

KB: Exactly.

CDN: And in the ’50s, that was the dawn of the jet age. Are we on the cusp of another grand transformation?

KB: Electric cars are fascinating because, unlike a big V8 or V12 block that you have to fit in a specific place, electric drivetrains are extremely packaging-friendly. Motors can be placed at or between the wheels. And the batteries? They’re like stacked chocolate bars—you can put them almost anywhere.

Now, for efficiency reasons, some companies go with a big battery pack underneath the seats. That raises the seat height, raises the whole silhouette of the car, and ultimately, you lose some of the excitement and spirit of a sports car.

What we did on the GranTurismo, well, on the electric version, not this one, is we simply removed the engine, gearbox and driveshaft, and used that space for the batteries. This kept the batteries between the driver and passenger, the seats stayed low, and the centre of gravity remained low and central. So we hit all the right marks: check, check, check.

What’s beautiful is that electric allows every company to make its own decisions. Some raise the driver, we chose not to. And I think that’s fascinating.

That’s one side of it. Then, in terms of design tools, sure, we started with drafting, Canson paper, Photoshop. Now you’ve got designers going straight to Blender. Some don’t even sketch anymore. And of course, now we have AI.

We could spend three more hours talking about the right and wrong ways to use AI. But what's also interesting is that, culturally, everything is moving so fast. Five years ago, you could still predict where society might go. The pace of change was slower, a bit more predictable. But now? Every week, something new happens, and you barely remember what happened the week before.

That all influences design, even if people don’t always see it. After 9/11, for example, beltlines rose, windows got smaller and people wanted to feel more protected. These events have a huge influence on car design. And we’ll see where it all goes next.