McLaren Speedtail - the inside story

Like an F1 car but with a different mission, the Speedtail sets a new benchmark for speedy comfort, as Rob Melville and his design team explain

The word ‘unique’ is thrown around a lot in automotive circles, but it’s rare for a design team to tackle something as unusual as a three-seat production car with a central driving position. The list of such vehicles is exceedingly brief, but has now gained a new entry with the arrival of the McLaren Speedtail. “The look and feel of a car needs to meet its mission, and in this case the mission was to create the world’s first three-seater hyper grand tourer,” says McLaren Automotive design director Rob Melville. “That means you can travel at speed, across continents, in supreme luxury, with luggage for three.” The words “at speed” are of course pivotal. Melville notes that a core benchmark for the car was to hit 300km/h (186mph) in 12.8 seconds, with top speed capped at 250mph (403km/h). “To do that, you need a unique powertrain,” he observes, adding that the parallel hybrid system developed to deliver those numbers dictates a big chunk of the vehicle’s packaging. Despite its extreme parameters, the schedule of the Speedtail project remained reassuringly familiar. “For most carmakers, from when the design team start sketching, it normally takes about four years until the car hits the road,” Melville says. “We’re not dissimilar in that regard.”

As a three-seat McLaren, the Speedtail cannot really avoid comparisons with the F1, its illustrious predecessor (pictured top and above). McLaren itself underscores the link via the Speedtail’s limited 106-car production run, exactly matching the numbers shipped of its forebear. Beyond the seating, however, Melville suggests that the two cars are not much alike. “The Speedtail is very different in its mission,” he says. “The F1 was for road and track, very similar to the P1.” By contrast the Speedtail’s grand touring brief calls for a more a relaxed sort of beast – if relaxation is possible in a 250mph car. The F1 did yield plenty of useful data, however. “We have a fairly good insight into how people use those cars,” Melville says, though he firmly rejects the notion that F1 owners had influence over the newer car. “No, no, no,” he says. “We don’t design by committee. If you involve everyone and ask everyone what they want, you end up with a really diluted, wishy-washy pastiche. For us, it’s about confidence in what we do.” The quarter century since the F1’s debut has of course witnessed huge progress, not least in carbon-fibre construction techniques. The F1’s hand-laid tub soaked up 4,000 hours of labour, for example, whereas a modern McLaren monocell can be made in about half a day.

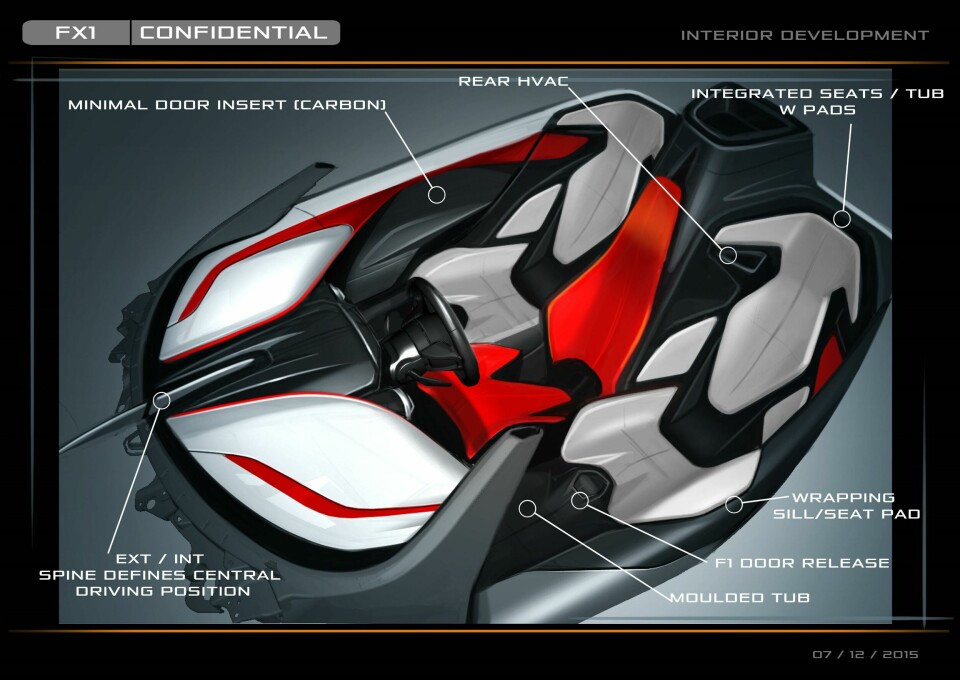

Today’s structures also demand fewer compromises. “On the F1, there’s a tunnel either side of the driver that you have to get your feet over – it’s quite awkward,” Melville points out. “For its day it was quite advanced, but we wanted to move things on. We have a completely flat floor and you’re able to get your feet across, so ingress-egress is much easier.” The twin rear seats of the Speedtail were also designed as a fixed part of the carbon tub. “The seat pads actually sit on the monocell – the comfort sections from the ergonomics team were all designed into the carbon fibre,” Melville says, noting that this structural multitasking saves a lot of weight. The Speedtail’s layout was firmly mid-engined from the outset, but Melville says his team was keen to keep overall length in check, despite an arrowhead seating layout that adds length compared to a two-seater format. “Overall it’s just over 5.1 metres, and that is really dictated by the passenger layout,” he says. “Everything else we fought for every millimetre, to keep the car as short as possible, because length adds mass and mass is the enemy.” With the basic packaging constraints defined, the team embarked on a detailed design development process that relied on traditional sketching and clay modelling as well as cutting-edge virtual reality.

“Tools do make a difference,” Melville observes. “We still start with pen and paper sketches, or sketching straight onto a tablet or Cintiq. Then we quickly get into 3D design, where we use Alias as well as a new tool called Vector Suite, which is really hot off the press. We developed it in-house with a local software developer.” The software, based on the games-orientated Unreal Engine, supports design interaction directly in virtual reality. It was used to define the major volumes and interfaces for both the interior and exterior of the Speedtail, Melville says. “We’re able to put a VR headset on and sketch the car out in 3D,” he explains. “You can be sat at your desk and make it full size, zoom out, have a look at the whole car, come back in, work on the model, zoom back out, or work on a scaled version. Your workspace becomes almost infinite.” Melville adds that digital tools are becoming increasing vital for interior work. “We’ll produce the data and machine it into low-density blue foam, for a very quick, basic look,” he says. “We’re able to get a feeling for the interior environment; the space. Is it claustrophobic? Does it feel light and airy? Where do the controls need to be? Can you see where the front fenders are? Seeing the peak of the front fenders really helps to position the car on the road.” McLaren Automotive always places the front fender apex directly above the axle, providing a visual reference point that is as helpful for avoiding kerbed alloys as it is for clipping the apex on a track, Melville explains. “We say ‘designed around the driver’ at McLaren, it’s one of our mantras,” he adds. “For us, the interior and exterior work together. When you look outside, what information do you get back?” After these exploratory stages in two dimensions, virtual reality and milled foam, the team still relies on clay modelling to perfect the final forms.

“I know digital is catching on more and more but ultimately it’s a physical product,” Melville argues. “You need to be able to see it, sit in it, get a feel for the space, and understand where you put your hands when you want to climb out.” Beyond the clay stages come validation models leading to the final validation model – the car exhibited at Geneva in March. “Then we just have to make sure it’s delivered perfectly into production over the remaining eight to twelve months,” says Melville.

Three key phrases guided both interior and exterior design, and the look and feel of materials: “Sleek and seamless; formal dynamic; and bold elegance,” Melville explains. “We wanted a car that captured the spirit of art and science, not just science.” He describes McLaren’s Senna as the company’s most science-focused car, both inside and out, comparing it to a military project or a 100-metre sprinter. “Speedtail is like an Olympic swimmer,” he adds. “It’s about long, lean, elegant muscles.” Striving for a sleek and seamless look led to glazing that wraps smoothly up and over the driver’s head. “We’re able to integrate an electro-chrome function, so you don’t need sun-visors,” Melville notes, adding that the ability to darken the top of the canopy at the touch of a button “makes the cabin feel more open, more spacious, and takes weight out”. Speedtail design manager and lead exterior designer Steve Crijns adds: “The exterior form language is very much aerodynamics driven, which has a certain romance to it: sculptural and beautiful speed-forms. On the interior, we wanted to continue that form language, to make sure we got beautiful flowing lines, so the interior and exterior would connect.” Of course the arrowhead seating layout runs counter to the aerodynamic ideal of a classic teardrop shape in plan, but makes up for that deficit in other ways. “The real win is the driving experience,” Melville says. “You’re sat in the middle of the car, so you’ve got this fantastic visibility of the road ahead no matter where you’re driving. If you go from the UK to mainland Europe, it feels really natural to drive because you’re in the middle of the car.”

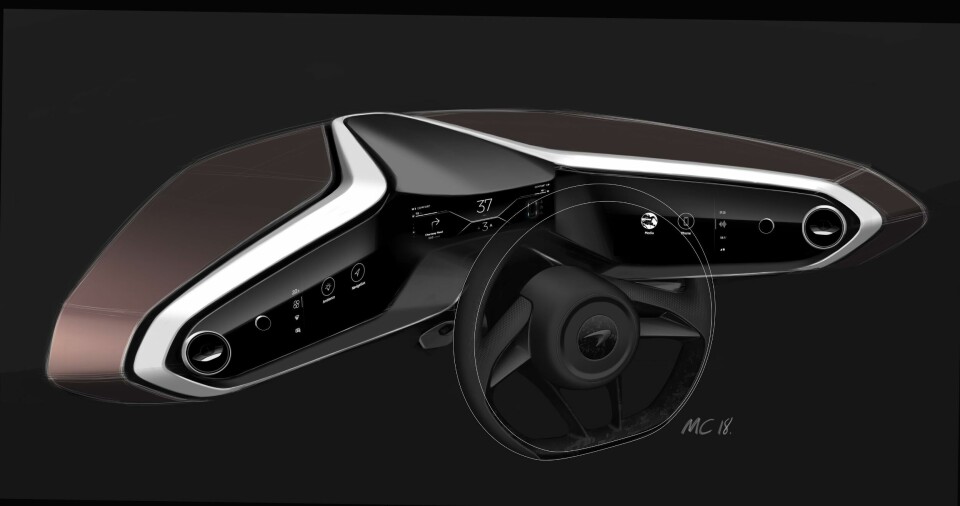

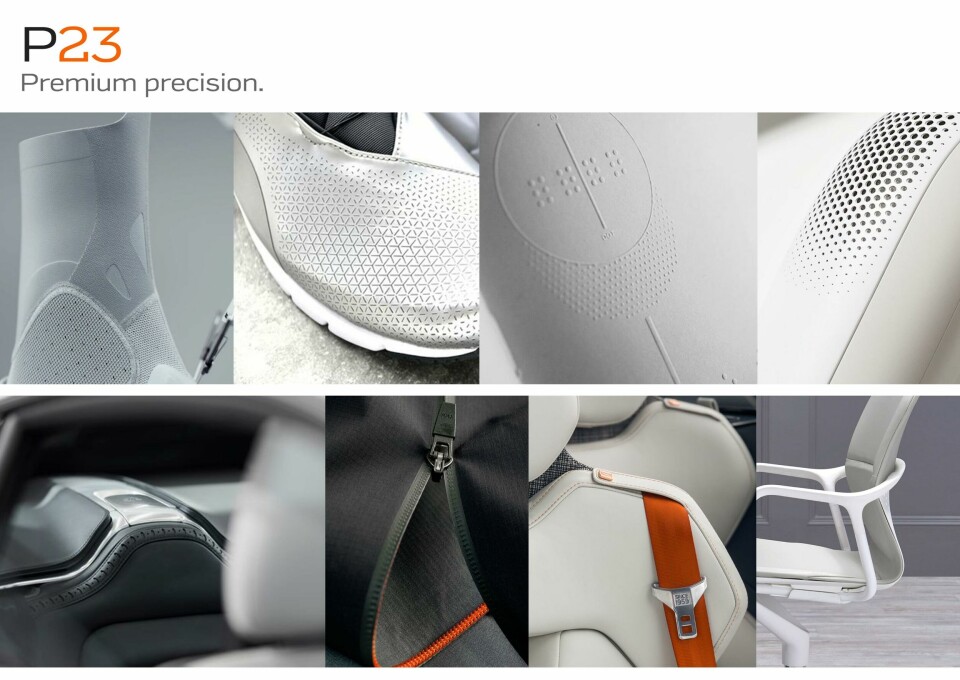

The central seat naturally favours a symmetrical IP layout. The Speedtail’s middle display provides driving information, with a climate control screen to the left and an infotainment screen to the right. “Two blades of glass flow out and effectively morph from the central screen,” Melville says. “Air vents are set into the glass, rather than having a separate moulding – it’s about reduction, reduction, reduction; to deliver both visual elegance and reduction in weight.” At either end of the dashboard are additional rear-view monitor screens. Just as the original F1 design switched from high- to low-set door mirrors, so the Speedtail team assessed both low and high positions for the camera screens. Atop the dash, leather blades wrap around the rounded oblong forms of the screen housings. “We use beautiful analine leathers that are ultra soft and smell fantastic,” Melville says. “If you want to specify a very bright, light interior, we digitally print onto the leather so that it gets darker towards the screen, to prevent reflections, and fades into the lighter colour.” The approach allows colour changes without abrupt contrasts or joins between one section of leather and another. “Everything is very sleek and seamless,” comments lead interior designer Alex Alexiev. “There are very few cutlines on the interior – the leather from the fascia spills down into the lower environment. And the door card runs into the rear seat pads, so it’s a really clean intersection. We’ve used a lot of non-automotive, non-traditional ways of trimming the leather to make the interior feel like a carefully fitted glove.” Crijns adds that the interior was designed with easy customisation in mind: “Customers can do what they want with almost all the features.” Colour and materials design manager Jo Lewis singles out the hand-painted leather edge running around the top of the driver’s seat, a seam finish used in luxury luggage. “It gives an added element of personalisation, because you could change the colour,” she notes. “It requires real craftsmanship to get it right.”

Lewis says that the grades of leather used in the Speedtail cabin are not normally used in automotive applications. “The quality is much higher, and the way it wears will be different,” she says. “It will patina over time to give a beautiful aged effect.” Seating features a non-slip leather, with a nubuck surface orientated to let occupants slide in easily but feel gripped once firmly aboard. “It really makes a big difference,” says Melville. “When you want to get out you push up and out anyway, but when you’re sat in the seat you’re not sliding around.” Achieving the right perceived thickness for the driver’s seat was one of many challenges, balancing light weight against comfort.

Creating a sense of harmony between the interior and exterior, and between details and forms, similarly took time, Melville says. “We went through many iterations, working with suppliers to bring digital craftsmanship to life,” he adds. “The way we’ve used brushed aluminium with polished edges, the same as you might find in jewellery making, or thin-ply-technology carbon. It’s a grand tourer, but we couldn’t just put wood in there. We wanted to use our material, carbon, to deliver light weight but also to add an artisan feeling.” The milled carbon surfaces do provide an effect reminiscent of wood grain. “You’ve got all these different layers in different directions; it looks like waves,” Melville notes. “It’s a way of taking race-car materials but giving them an artistic twist.” Despite that creative aim, Melville says rationality remained the overriding goal – for every decision to be taken for a good reason. “Our design mission statement is to create breathtaking products that tell the visual story of their function,” he explains. He adds that bravery is just as important: “Take some chances, make some mistakes, because we’ve got to deliver something that’s fresh and different and challenges the way everyone else expects things to be