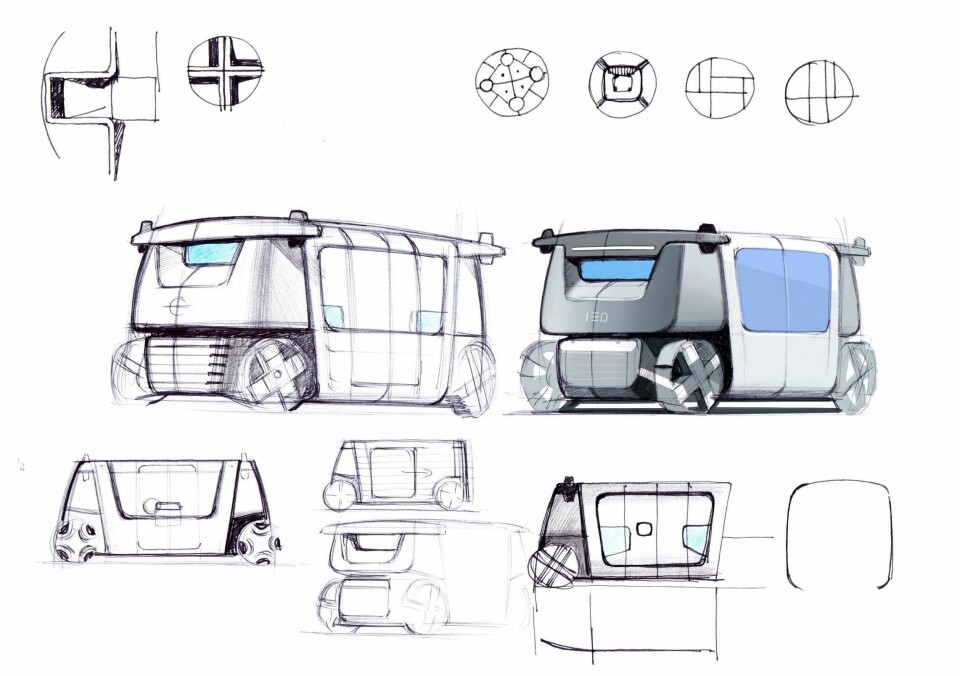

Mormedi's modular autonomous concept challenges conventional vehicle design

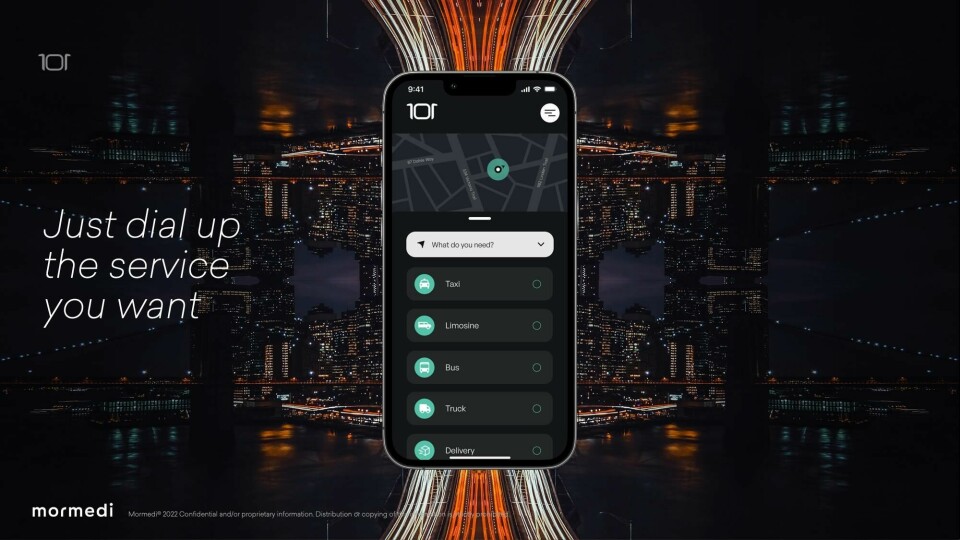

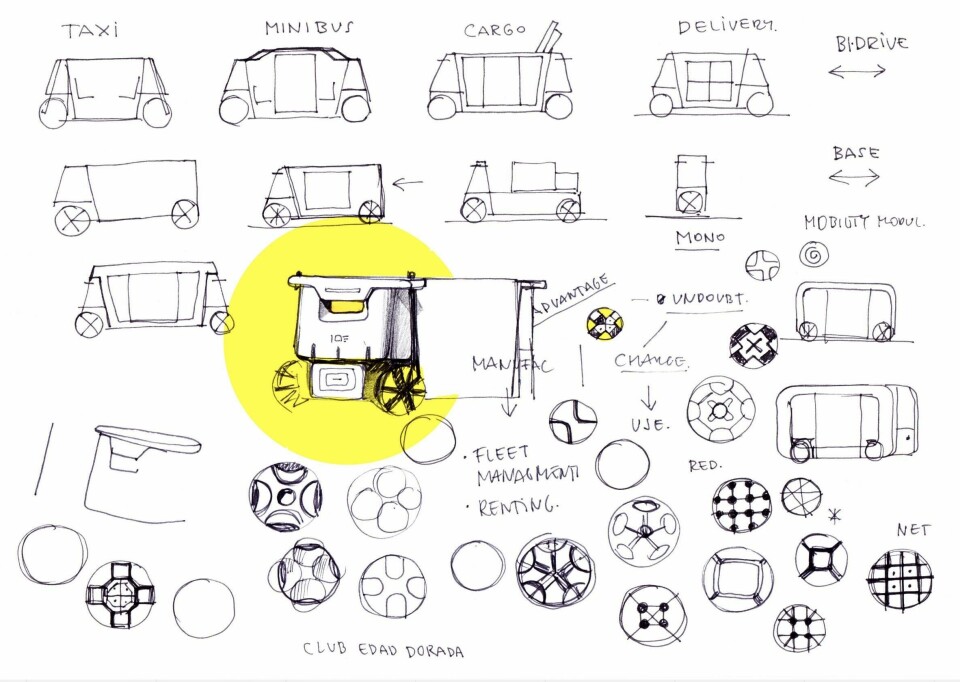

Design agency Mormedi has revealed its latest concept work, 101, which envisions an autonomous shuttle that shapeshifts between taxi, limousine, truck or last-mile delivery droid as needed.

The 101 concept from Spanish design house Mormedi is an overtly futuristic take on the ‘future of mobility’ and is one of many projects that foresees a ‘one vehicle fits all’ solution – available, inevitably, at the tap of a smartphone app.

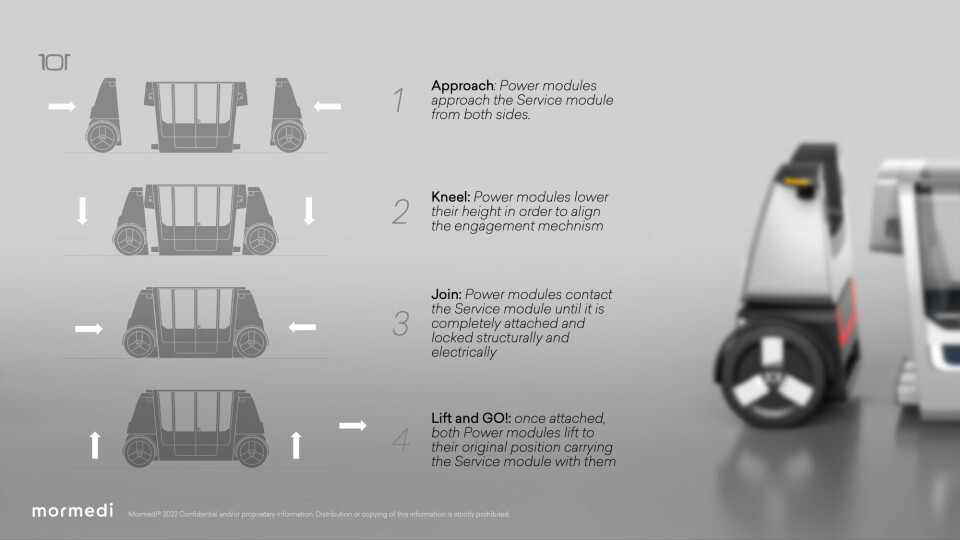

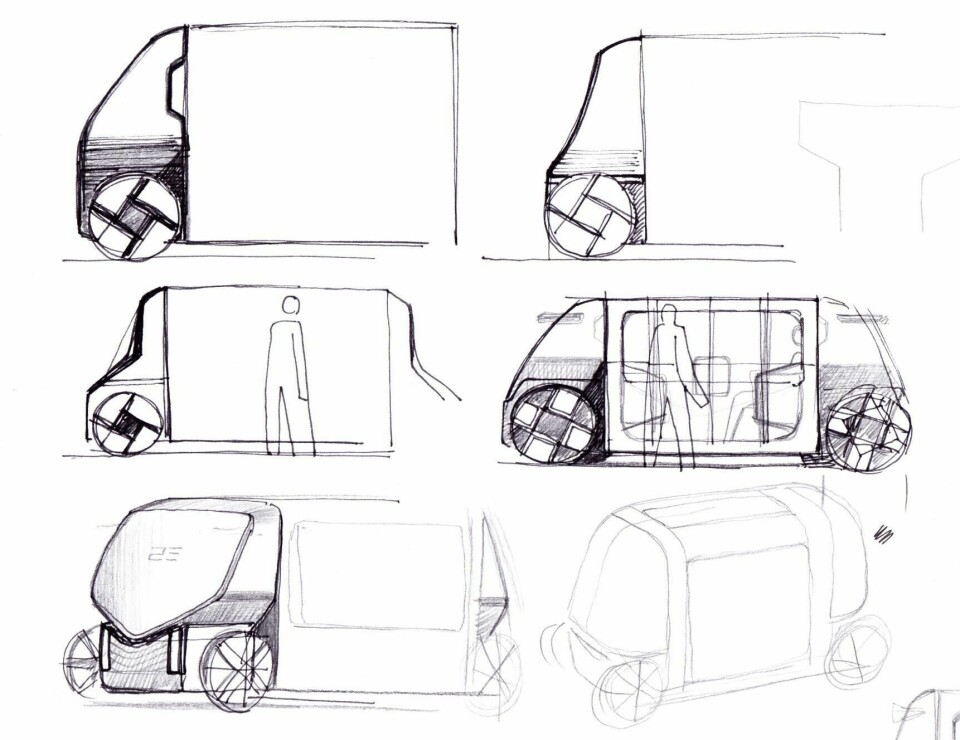

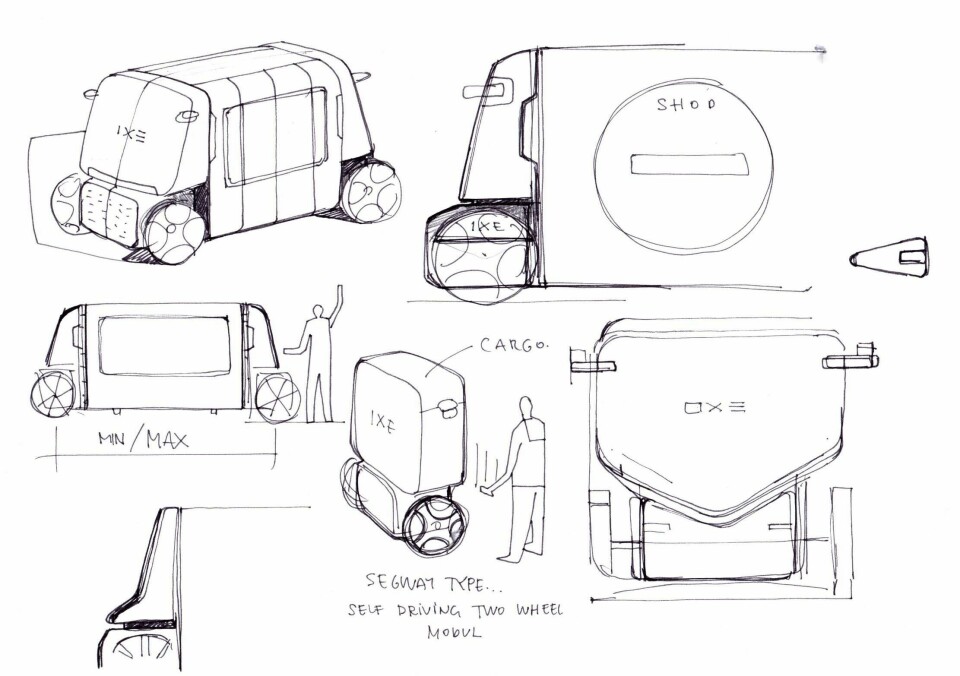

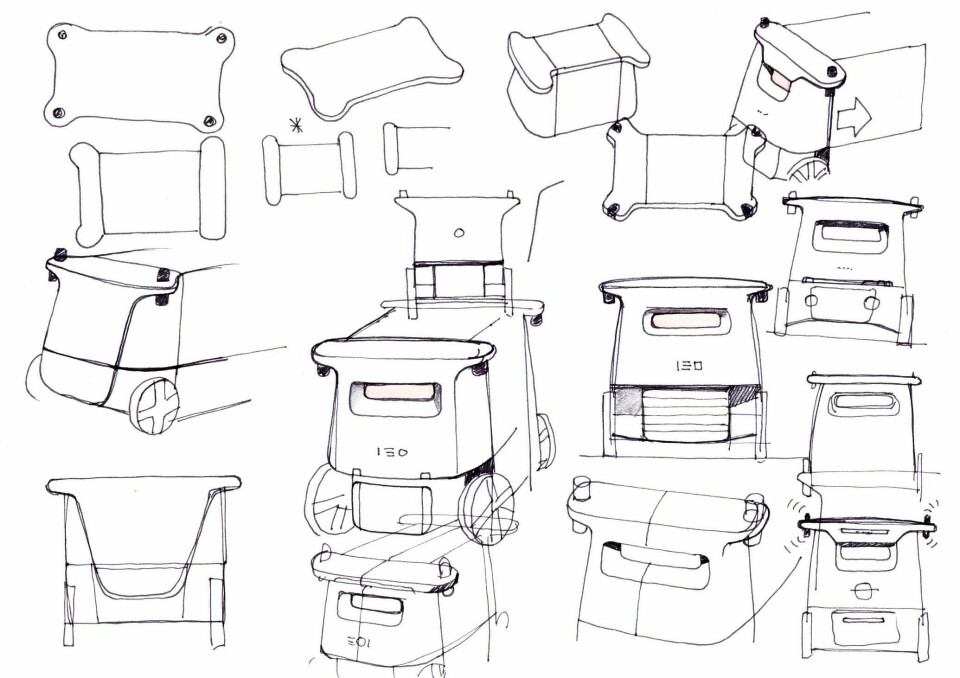

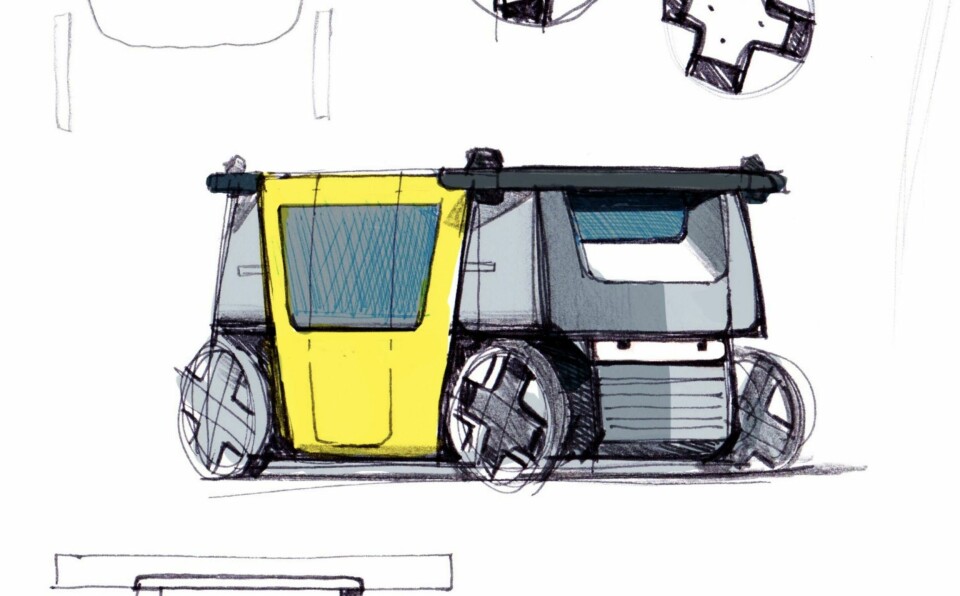

It hits all the right notes for a future mobility solution: driverless, electric, on-demand, modular. It looks the part, too, with renderings showing how powered modules at either end of the shuttle can detach and operate independently like Segways. These would shuffle off and deliver packages independently, before returning to the mothership. The central cabin which is sandwiched between two of these modules can be decked out as a comfortable and well-furnished people carrier, or a simple container unit for various commercial applications.

This kind of project is a little outside of CDN’s usual remit, of course. Mormedi’s VP of design Blake McEldowney even notes that the 101 was not seen as a conventional car design exercise but the creation of a system – drawing on his previous experience in product and mass transit design. However, the concept does lean on traditional car design principles for exterior and interior design, UX and CMF. Particularly in people-carrier form, there is a heavy emphasis on materials, layout and how passengers (and other road users) will interact with the vehicle. All this is relevant for future autonomous vehicles being hatched up by traditional car brands, of which there are many.

Visually, it is similar to any of the shuttles presented by the likes of Navya, Toyota or Zoox. There is no traditional front or rear end – it is symmetrical. The design was driven by the proposed functionality of the vehicle, which aside from the obvious challenges of splitting into different parts also included ground clearance, turning circle and where the batteries would be packaged (these are located in the power modules, which look like Star Wars droids when separated). “We didn’t have the full length of the vehicle to put batteries in the floor like most EVs do, so we had to create space in that power unit to make it realistic,” McEldowney said.

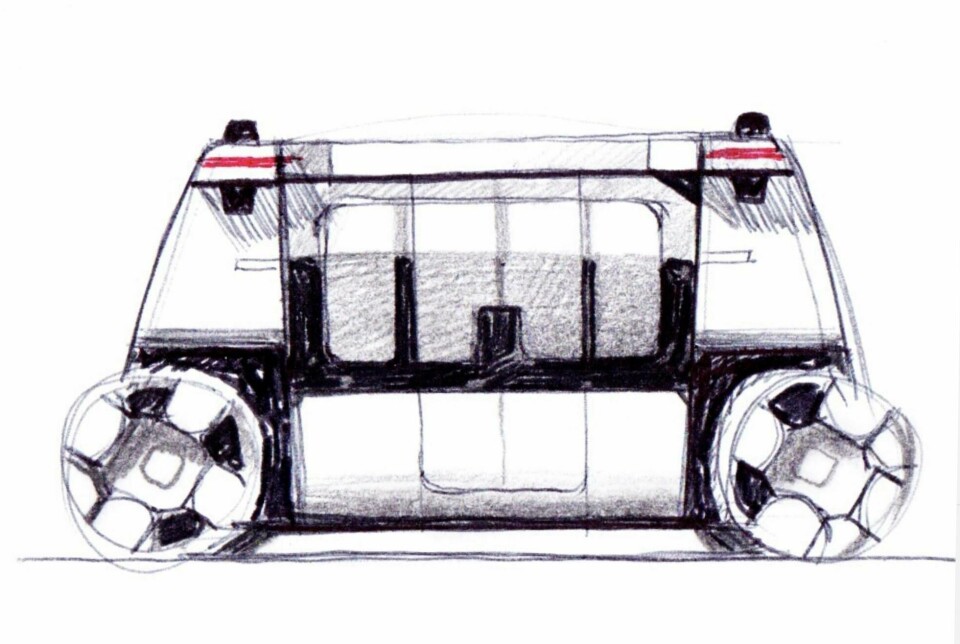

Given it is autonomous, there is no need for a wide front windscreen, with that real estate taken up by the power modules, LiDAR sensors and exterior lighting instead. These are not high-powered lamps for visibility’s sake, but more so for the benefit of other road users or pedestrians. “We also didn’t want it to look super stylish, and instead more utilitarian. It should feel more like a truck or a taxi,” he said. “The design came from the construction of those different elements, but we of course wanted something that looked interesting, technology forward, and not too static looking – even though we know we have a difficulty creating swooping lines from front to back.”

Aesthetics came after to ensure it would be appropriate to be on the street. If it was made entirely of glass, it would never work

The team also drew inspiration from drones and droids of sci-fi – evident in the innocent face created by LEDs in the lower mask of the power modules at either end of the vehicle. The flat face of a heavy-duty truck also came into play as it created space in the cabin. Although care was taken to ensure this concept would not look out of place on the road – “we didn’t want it to be too intimidating” – it was primarily an engineering exercise. “Aesthetics was driven by the functional need for sure, but we didn’t want it to look like a stack of Lego bricks,” says McEldowney.

”We wanted to make sure it had a feeling of cohesiveness while it was reconfiguring to different vehicle types and that those modules would offer an appropriate mix of modularity,” he continues. “Engineering was pivotal in driving the design to ensure this could be real; aesthetics came after to make sure it would be appropriate to be on the street. If it was made entirely of glass, it would never work. It was about finding a balance of visibility for passengers, strength where needed and elegance.”

He suggests that more broadly, the symmetrical nature of some upcoming cars (see Canoo, for instance) is changing how designers approach the interior compared to a typical car. “I think that’s opening up a range of new possibilities,” McEldowney says. “When it becomes autonomous and you don’t need a driver to see certain things or be comfortable in traditional ways, that’s when form factor changes start to come in and be driven by functionality. Maybe in future generations we’ll see some nuance, but for now it’s about: how do we make this work from an autonomous and engineering perspective?”

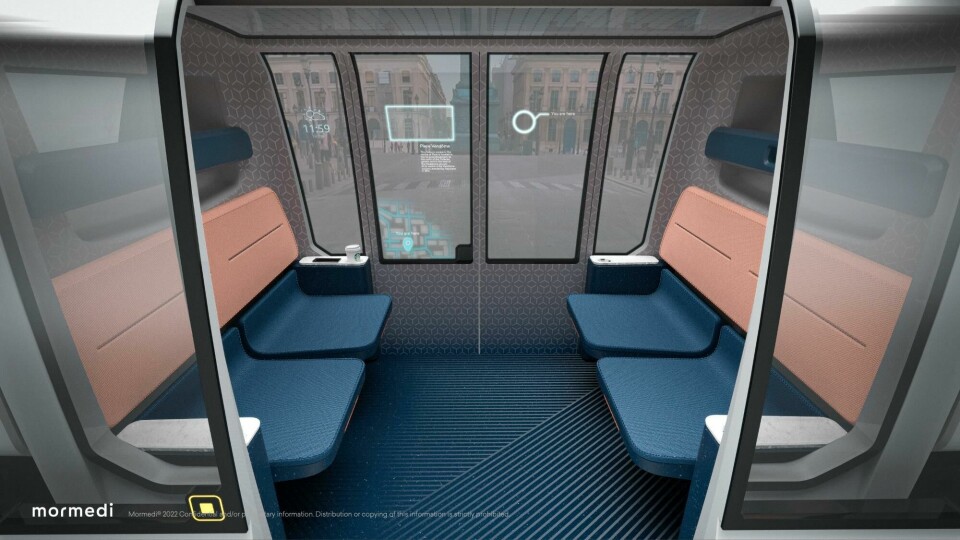

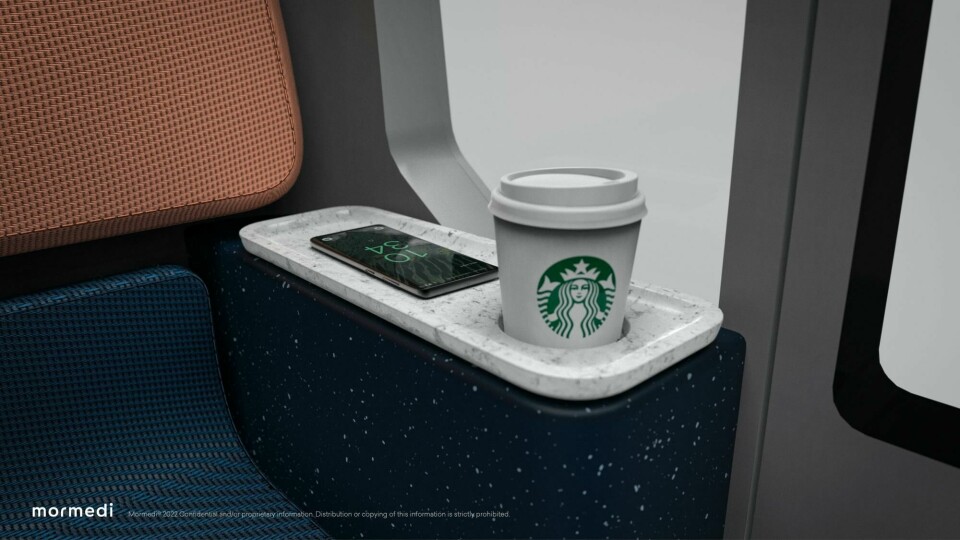

Customisation was a driving trend for the interior. The cabin would look very different if it is shifting cargo, for example, compared to when it is ferrying the rich and famous in limousine form. With the former, the interior would be “robust” says McEldowney, “using strong materials that wouldn’t be easily damaged – or even look better as they age. If it is a taxi, limo or rolling office mode, we would look at an interior that is appropriate both in terms of the form and function but also clearly CMF. It gives us so many options and becomes a lot about traditional interior design.”

At the rear we had to use brake light colours and indicators, but also animations to show its direction of travel or to give people a sense of what is happening

Thought went towards the orientation of seating and even whether people might get travel sick, but the team at Mormedi stayed clear of putting forward a definitive plan for the layout, opting to leave that open for future discussions. “In the taxi variant, we kept it traditional with face-to-face couch seating, for example. Where it gets more complicated is if it was a meeting room – what does that experience work on a practical level? We think it could work, but we didn’t full design all those different options for this project just yet.”

The user experience also needed to be thought out from an exterior perspective – not something a car designer typically has to consider, although this is changing. This concept would need to communicate with pedestrians or other road users, indicating left and right as usual but also whether it is about to stop at a junction or if it is allowing people to cross the street. “Indicating the vehicle’s intentions was why we wanted to have flexible LCD screens, or the way we treat the lighting effects to indicate where we are going. At the rear we had to use brake light colours and indicators, but also animations to show its direction of travel or to give people a sense of what is happening.”

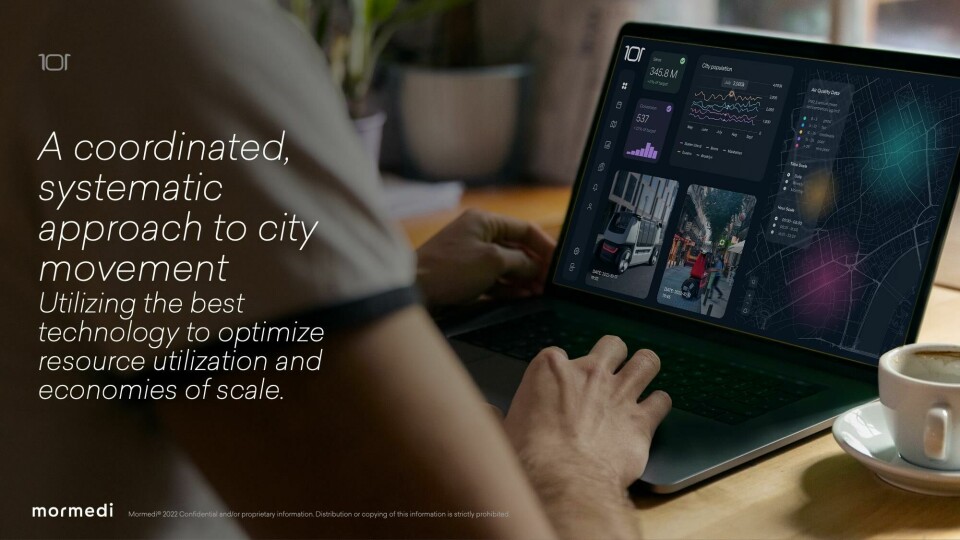

The 101 concept was borne from an exploration of urban mobility challenges. Or, in simple terms, mounting congestion and low vehicle utilisation. A modular vehicle like this might be able to remedy some of those challenges and offer an alternative to car ownership, suggests McEldowney. “It was a look at how human drivers and AVs could live with each other in the city. We also considered sustainability issues that all manufacturers and ‘movement providers’ in general are dealing with; privately owned vehicles are inactive for more than 90% of the time. That’s a ridiculous number. We considered what other things could be moved in a city, and we came up with the solution from there.”

The 101 feels a little less far-fetched than it might have done a few years ago, but it would still be a stretch to suggest this is a near-term solution. Although a digital concept for now – aside from basic card models for a sense of scale – the design team is in conversation with various players to see whether there is scope to move it further and produce a working concept of sorts. “It’s not for everyone or for every city, but you can see the benefits of making something like this work,” McEldowney concludes. “We’ll see what the reaction is like and decide on where we go from there.”