Ten cars that defined the Art Deco era

Car Design News looks back on an era of fabulous automotive designs, many of which emerged in some of the darkest moments in modern times

The period between 1925 and the Second World War saw the creation of some of the most beautiful cars ever built. Here, we take a look at ten of the Art Deco classics that might help to define automotive design in that era.

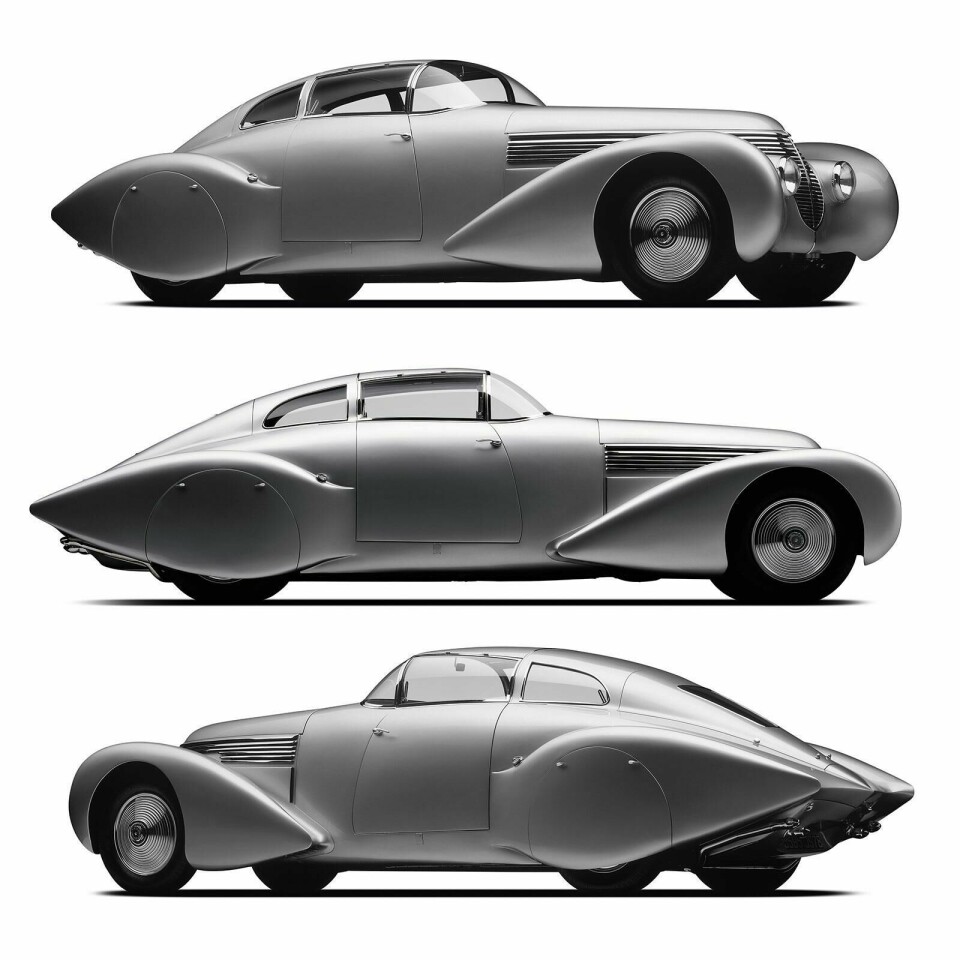

Hispano-Suiza H6B Dubonnet Xenia (1938)

A bespoke ultra-luxury car built on the chassis of a Hispano-Suiza H6B, the Dubonnet Xenia has a long and storied history. Built for French pilot and racing car driver Andre Dubonnet, the Xenia was designed by the client and by Jean Édouard Adreau, and built by Saoutchik. The car has a unique racing suspension (designed by Dubonnet), aerodynamic body work (again, by Dubonnet) and unique seating and interior. The name, Xenia, was a memorial to Dubonnet’s second wife, who died suddenly in 1936.

The car disappeared in World War II, emerged afterwards, changing hands several times. It was brought to America at the turn of this century and restored. It was bought by Peter Mullin in 2003, underwent further restoration, and remained in Mullin’s collection until his death. It can now be seen at the Petersen Automotive Museum in Los Angeles.

Pierce Silver Arrow (1933)

Pierce-Arrow was a luxury car manufacturer in the US in the early part of the last century.

Its cars were once ordered by The While House to serve on State occasions, and Hollywood royalty, but by the 1930s the marque had fallen on hard times. As a way from breaking from the past, the Pierce Silver Arrow was introduced. An ultra-premium sedan, it promised the latest in technology (such as it was) and luxury plus modern aerodynamic styling. Five Silver Arrows were made and shown to great acclaim around the country. But the actual production cars were a disappointment – too many features were eliminated. The Silver Arrow died a quiet death, as did the marque in 1938.

Bugatti Type 57 1934-1940

The Bugatti Type 57 was a Grand Touring car designed by Jean Bugatti, son of Ettore, Bugatti’s founder. The original Type 57 was soon accompanied by the Type 57 S/SC, which were lowered and in some cases, supercharged. Several famous variants were created, including the Atalante, the Atlantic, and some subvariants.

The most famous, and emblematic of those years, was the Type 57 SC Atlantic Coupé. It was developed from the Aerólithe prototype, which had a body made of Elektron, a metal composed of 90% magnesium, and 10% aluminium. Elektron’s highly flammable nature meant it could not be welded, hence the raised dorsal seam running along the spine of the car. Subsequent cars were made of aluminium, but were still riveted along the dorsal seam. The seam, and the swoopy curves and rounded coachwork made for quite the Art Deco statement.

Only four of the Atlantic coupés were made. Three are accounted for (American fashion designer Ralph Lauren owns one), and it estimated that the fourth, if it still exists, would be worth £90 million at auction. That might be worth rummaging around in a few old barns, just in case you are up for a treasure hunting challenge.

Phantom Corsair 1937

Developed by Rust Heinz, a scion of the family of the famous American brand of condiments and pickles, the Phantom Corsair was intended to be the first of a number of custom cars for the Hollywood set in the late 1930s. At the time, it was not unusual for a well-known star to have his or her bespoke car built over a standard frame. Harley Earl and Howard ‘Dutch’ Darrin got their start this way, and Heinz, who had experience designing boats, was convinced there was a market for his services in Tinseltown.

The proof-of-concept was the Phantom Corsair, the ultimate villain’s car: a black on black on black two-door sedan. Its design reflected the ultimate in Streamline Moderne design and was built on the chassis of another streamlined classic, the Cord 810. The car garnered enormous attention for its elimination of fenders, running boards and futuristic features like push-button door openers, rubber and cork safety panels, and solid rubber seat foundations, eliminating springs and traditional seat frames.

The overall shape of the exterior was rather piscine, a smooth composition of body and glasshouse that seemed more like a whale or shark. The long (six meters) body had a pointed snout that further emphasized the marine animal image. The headlights were designed to project powerful beams forward and they rose just above the level of the like eyes projecting from the body of some hitherto unknown sea creature. Fog lamps were placed just above the bumper for additional lighting in inclement weather.

Delahaye type 165/175 1937-1948

Delahaye was French manufacturer of limited production bespoke luxury cars, and paradoxically, numerous utility vehicles including truck, utility and commercial vehicles and fire engines. In the 1930s, Delahaye became well-known for racing, developing innovative drivetrains and setting numerous speed records. Some of these chassis were fitted with ultra-luxury coachwork from such Carrosserie as Saoutchik, Figoni et Falaschi, and others.

These were fabulous Art Deco statements, with flowing bodies that were like an Erté evening gown transformed into automotive form.

Sadly, Delahaye would succumb to the many economic problems in France during and after World War II. And though there was continued interest by the Carrosserie until the very end, they could not delay the inevitable and Delahaye was folded into larger vehicle conglomerates in 1954.

Chrysler Airflow 1934-1937

Streamlining and aerodynamic design caught the public’s eye in the early 1930s, and Chrysler, hoping to capitalise on the zeitgeist. It hired Orville Wright, of Wright brothers fame, to help design a wind tunnel (the industry’s first) and aerodynamically tune the car. The front end shows the most dramatic results of its efforts – a smooth rounded hood and fenders, a dramatic “waterfall” grille and integrated hood ornament definitely announced that the future was coming at you. It also employed a steel unitised body, another industry first. Chrysler ads announced: “Suddenly, it’s 1940!”

Unfortunately, the public wasn’t quite ready for the streamlined future that the Airflow promised. And this, despite Chrysler having the ultimate symbol of the Art Deco age, the Chrysler Building. Sales were poor, and car was lampooned in the press. Each subsequent year, the car grew a little more conservative in its appearance, until finally the car was removed from the 1938 lineup, just as the rest of industry was catching up in the streamlining department.

Stung by the poor reception the Airflow received, Chrysler retreated to a more conservative design position, letting others take the lead. It even retreated from unitised bodies. This lasted until the mid-1950s when, in desperation, Chrysler brought in Virgil Exner refresh the lineup. This he did in dramatic fashion, sleek, befinned steel unitised bodies riding much lower than the standard Detroit iron. The change came with a corresponding increase in sales, and an unexpected bonus: Ford and GM styling studios were in a panic trying to catch up. The tagline in Chrysler ads of the period? “Suddenly it’s 1960!”

Lincoln-Zephyr 1936-1942

Sometimes it is nice to be fashionably late to the party. Such was the case with the Lincoln-Zephyr, a sedan and coupé from Lincoln. Positioned between Ford’s top-of-the-line sedan and Lincoln’s Model K, the Lincoln-Zephyr (the name was both a model name and the name of the marque) was introduced in late 1935 as a 1936 model. It drew heavily from the Pierce Silver Arrow and the Chrysler Airflow, thought it did not look like either one. But it had a steel unitised body, was aerodynamically tuned, very well proportioned and styled just slightly ahead of the times.

The Lincoln-Zephyr was Edsel Ford’s masterstroke of design (aided by his design chief bob Gregorie). Unlike his father, Henry, Edsel was an aesthete, dedicated to enjoying and curating the finer things in life ( Old Henry had bought Lincoln to keep Edsel busy and out of the way- he never expected the marque to be a success). The Lincoln-Zephyr embodied Edsel’s sense of good taste, and even in hard times, it sold well until the second World War interrupted production. After the war, the car was just called Lincoln and soon gave way to the Continental, which remained the marques’ flagship, remaining in production for some 51 years, though not continuously.

Rolls-Royce Phantom I 1925/1934

This Rolls-Royce Phantom I was constructed in 1925 and fitted with a Hooper Cabriolet body for its first owner, Mrs. Hugh Dillman of Detroit. There is no evidence it ever left England, and after changing hands for a couple of times, it was sent in 1934 to Jonckheere of Belgium to be “remodeled” with a new, more fashionable body and interior.

The result was a wonderful mélange of Art deco styling elements, including round doors, sunburst side windows, tailfin, and a sloped version of Rolls-Royce’s signature grille. A superbly eccentric Art Deco sculpture, all the more powerful because it began life as a custom, but traditional, Rolls-Royce.

The Phantom I passed through several hands in Europe, the US and Japan and endured lots of neglect before finally coming into the collection of the Petersen Museum in Los Angeles, where it can be still be seen in the collection.

Cord 810/812 1935-1937

Introduced at the New York Auto Show in late 1935, the Cord 810 was a smash hit. Crowds at the Waldorf Astoria hotel, where the show was held in those days, pressed in so tightly that some attendees resorted to standing on the bumpers of competitors’ cars displayed nearby to get a better look.

There on the Cord stand, near its Auburn and Duesenberg cousins, was a sleek sedan with a radical new face, one that would define its era and become an American automotive classic and icon of American automotive design – and one that would be enshrined in the Museum of Modern Art in New York some 16 years later.

Central to Cord’s visual identity was its prominent hood, which soon acquired the nickname “Coffin Nose” (it was, in fact a clamshell hood, the first on a production car). A grille of horizontal louvers ran around the sides of the engine compartment and across the nose.

Supercharged models had chrome exhausts penetrating the louvers which added real glamour to the car, but diminished its streamlined look.

Flanking the nose was a pair of sleek fenders with retractable headlights. The headlights, which were raised by hand with a crank just to the left of the steering wheel, were adapted from the landing lights of the Stinson airplane (a company also owned by Cord). They were the first retractable headlights ever on a production car.

Excitement about the car led to enormous number of orders which were promised by Christmas of 1935, but, unfortunately, few were delivered. Those that were delivered had technical problems and disappointment hung over the company throughout 1936, with mechanical problems and delays plaguing the Cord’s production. These problems were never overcome and the Cord was quietly retired in 1937.

Chrysler Thunderbolt

Perhaps the ultimate in Streamline Moderne, the Thunderbolt in many ways put an exclamation point on the era, as World War II was already raging in Europe and was just months away from starting in the Pacific. The design shows the best and the worst of the Streamline Moderne.

On the one hand, the streamlining aesthetic subordinated everything to the smooth masses and lines, characteristic of optimal aerodynamic (and hydrodynamic) forms. On the other hand, too much of a good thing is, well, not so good. If every bit of character in the form is smoothed out, what is left? An automotive form that seems closer to the shape of a bar of soap. The Thunderbolts (six were built in several variations) were an appropriate end to Art Deco and the Streamline Moderne. Postwar cars, were looking towards a new aesthetic, one characterised by the detail below. The rest, as they say, is history.