ArtCenter’s Transportation Design Department breathes new life into old wind tunnel

ArtCenter’s storied programme moves into the Mullin Transportation Design Center at the College’s South Campus

For nearly fifty years, Artcenter’s Transportation Design Department was housed in a steel and glass structure perched on a promontory overlooking Pasadena and Los Angeles. But now the programme has moved from its lofty heights to a location near downtown Pasadena, closer to the urban heart of the area.

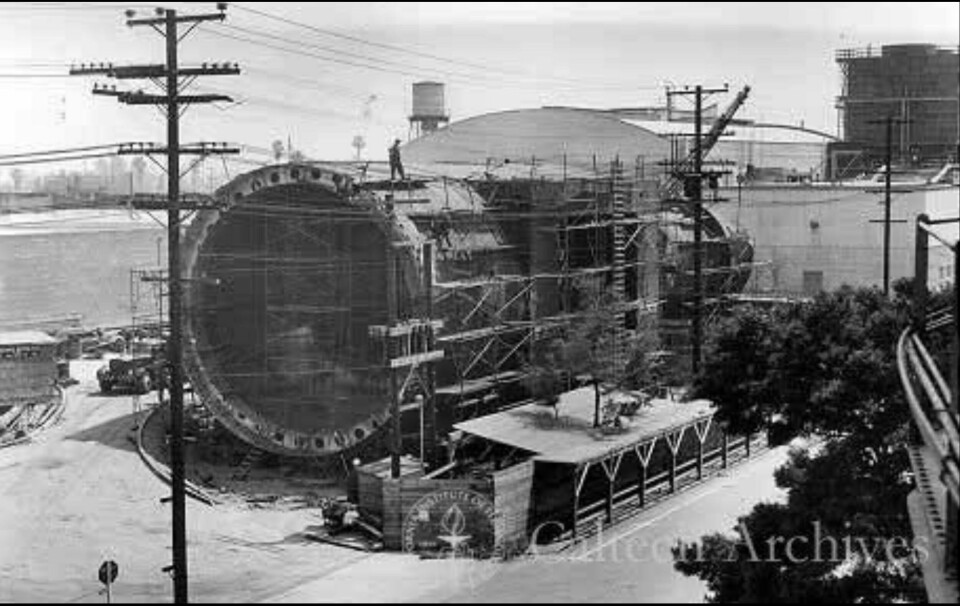

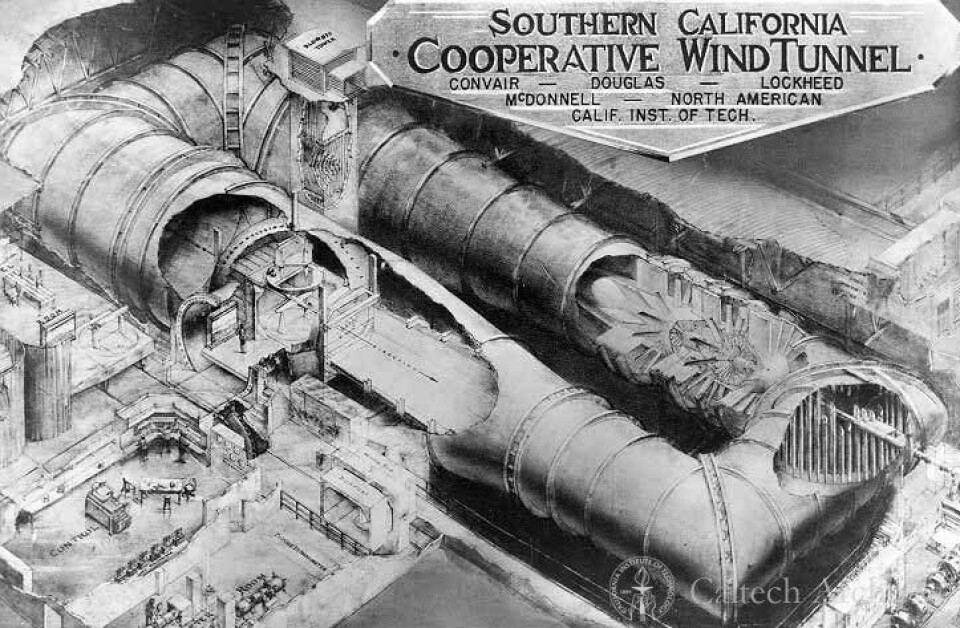

The Mullin Transportation Design Center, as the new facility is called, is inside the shell of the former California Cooperative Wind Tunnel, built during World War II by a consortium of aircraft companies and the nearby California Institute of Technology. The facility was the first supersonic wind tunnel and was the testing place for a generation of both subsonic and supersonic aircraft including the SR-71 “Blackbird” spy plane.

The wind tunnel has long since been replaced and located on the Cal Tech campus. The building’s shell was bought by philanthropist Peter Mullin two decades ago and used by ArtCenter for classrooms and a very large art gallery, after a dramatic renovation by Los Angeles architects Daly/Genik.

Today the 950 building, as it is commonly called, has been remodeled with the Mullin Transportation Design Center structure “inserted” inside the wind tunnel building (the two structures don’t actually touch). “It’s a bit of a ship in a bottle”, Darrin Johnstone, the project’s architect, noted.

Marek Djordjevic, chair of the Department of Transportation Design, sat down with us to discuss the curriculum at ArtCenter, and its relationship to the new facilities.

“Here at ArtCenter, my colleagues and I believe in a ‘both/and’ approach, meaning we will teach both traditional skills such as sketching and clay modeling, and new digital processes,” he told CDN.

“One thing that is important about a physical model is that is allows more ‘eye time’ on the design,” he continued. ”A digital model has a limit on the amount of time you can see it- it’s on or it’s off. But a physical model, as it develops, has more eyes on it, more time for review and discovery. Additionally, here we can bring real full-size cars into our open areas, and wheel out clay models, or virtual models in mixed-reality experiments.”

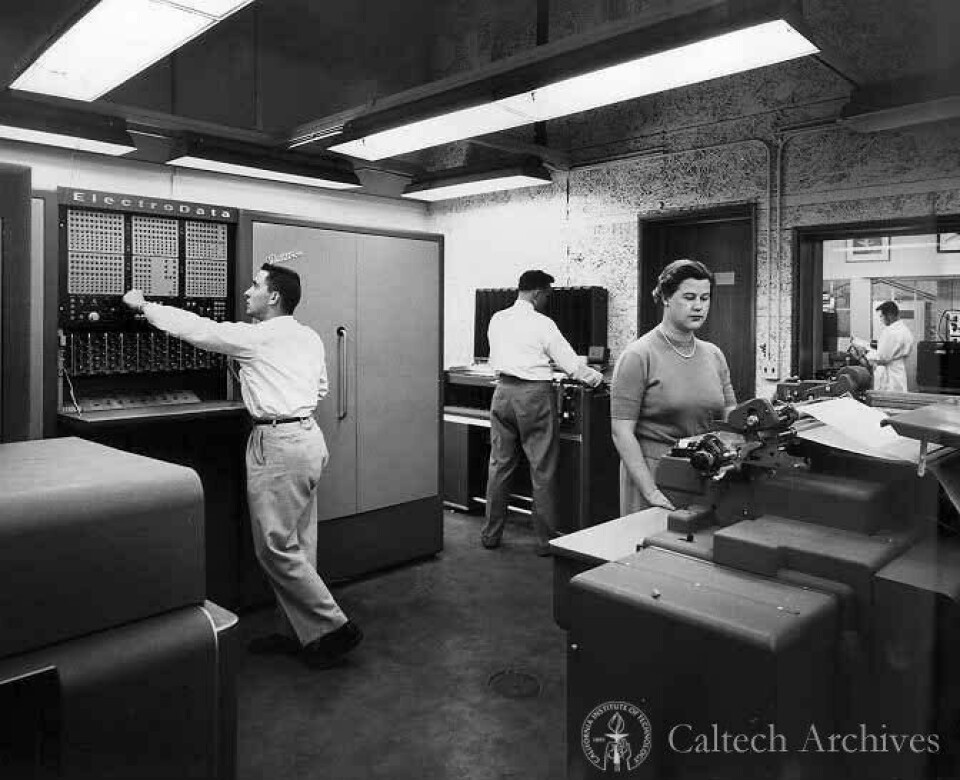

Djordjevic adds that, on the digital side, “tools have developed so much since the first days of Alias Wavefront to the newest powerful tool, Gravity Sketch. Our new facilities have the room for gatherings in both physical and virtual space, for creative teams working on vehicles in virtual and mixed-reality.”

The Hillside Campus, with its dramatic modernist slab, will not be going away

Elsewhere, he adds that the Genesis/Hyundai/Kia Mobility Experience Lab allows for large digital projections, both still and to simulate motion. “And our new expanded CMF library allows for design studies for student projects and with glass wall facing public areas, allows for passersby to be able to get a sense of what CMF is about,” he continues.

“Cross-disciplinary projects can be more easily accommodated in this new facility and we know that they will be part of the programme in the future. Cross-disciplinary studies allow students to see into the creative process from another discipline’s point of view. The Mullin Transportation Design Centre will be a great facility for these cross-disciplinary collaborations.”

The Hillside Campus, with its dramatic modernist slab, will not be going away. An icon of Late Modernism, architect Craig Ellwood’s steel and glass structure will continue to house multiple ArtCenter Departments, as well as the library and cafeteria and auditoria.

And a fair amount of nostalgia too. Franz von Holzhausen, Design Director at Tesla recalls: “It’s an inspiring moment when you arrive and drive under the bridge and swoop around up the drive. You feel like you have arrived at something special. You’re inspired by the building alone, and the possibilities the what might lie inside that black monolith of a slab.

“Los Angeles is a big city, raw, and in the middle of a landscape of smog, earthquakes, and fire,” von Holzhausen continues. “The Hillside Campus is this protected space where you can go and create and lose the worries of the world. It was compact, it was tight – we were all crammed into small studios – and we became like a family.”

Few will deny the iconic power of Ellwood’s Hillside Campus. It is a Late Modern acropolis, one dedicated to the arts, and one that is an artwork in itself. By comparison, the South Campus and the 950 building are more urban, and rough-edged. But this is an industrial area of Pasadena, and these structures were part of the vernacular in that part of the city. Still, like their earlier incarnations, these structures are more function than beauty and Ellwood’s, which, while not perfect, was a good combination of both.

As we sat and discussed these concepts with Darrin Johnstone, the project’s architect, he noted that the discussion around projects like these echoes that of museum design: “It’s a variation of the debate that goes on in museum circles – do you design a temple or a barn?” Meaning, is the structure to house art meant to be a functional structure where the artwork is the total attraction, or is the museum itself designed to be a work of art containing works of art?

In Los Angeles, there are several “temples” of art: the Getty, the Broad, MOCA, and the forthcoming new Los Angeles County Museum of Art building. There is also one prominent “barn”, the highly successful Temporary Contemporary, a renovated police car warehouse building designed by Frank Gehry while construction of nearby MOCA dragged on.

The Temporary Contemporary was so successful, that MOCA kept it permanently on as an adjunct gallery space called the Geffen Contemporary, and some say it’s a better space for art than the galleries at MOCA.

Johnstone also mentioned other influences for the final design include Fiat’s Lingotto ex-factory, and the Max Hoffman showroom in New York, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright.

The Mullin Transportation Design Center is definitely part of the ‘barn’ school, rather than a ‘temple’, but that doesn’t mean it is rustic and unsophisticated. The programme that shaped the design, developed over a decade, and with evolving technologies and pedagogy in mind, shaped the new facility-within-a facility. Advanced technologies combined with traditional techniques assure a more thorough investigative process and realistic presentations. It will prepare the designers of tomorrow for a world that Djordjevic describes as “more urban and more digital.”

It is an excellent fate for a building that housed the advanced (for the time) machinery necessary to test aeronautical experiments for supersonic flight. Now the transformed building will house designers and their experimental proposals for transportation solutions in an increasingly urbanised world. We look forward to those solutions in the coming years.