Car Design Review 7: Hartmut Warkuss – Lifetime Achievement Award

Hartmut Warkuss is awarded the Car Design Review Lifetime Achievement Award. In an exclusive interview, he talks about his career and offers some advice for the next generation of designers

Hartmut Warkuss might not be as high-profile as some of the more ‘showbiz’ late 20th Century car designers. But in an automotive career that started in the 1960s at Mercedes and Ford he went on to oversee the designs of seminal cars for Audi, VW and Bugatti from the start of the 1970s right through to the early 00s. During that time he also mentored numerous young designers that have gone on to have their own stellar careers as heads of design across various major global brands – including J Mays, Martin Smith and Thomas Ingenlath – and briefly became the VW Group’s first ever head of design in 2002. His combination of great designs, strong judgement and inspirational management is the reason he has been honoured with this year’s Car Design News Lifetime Achievement Award.

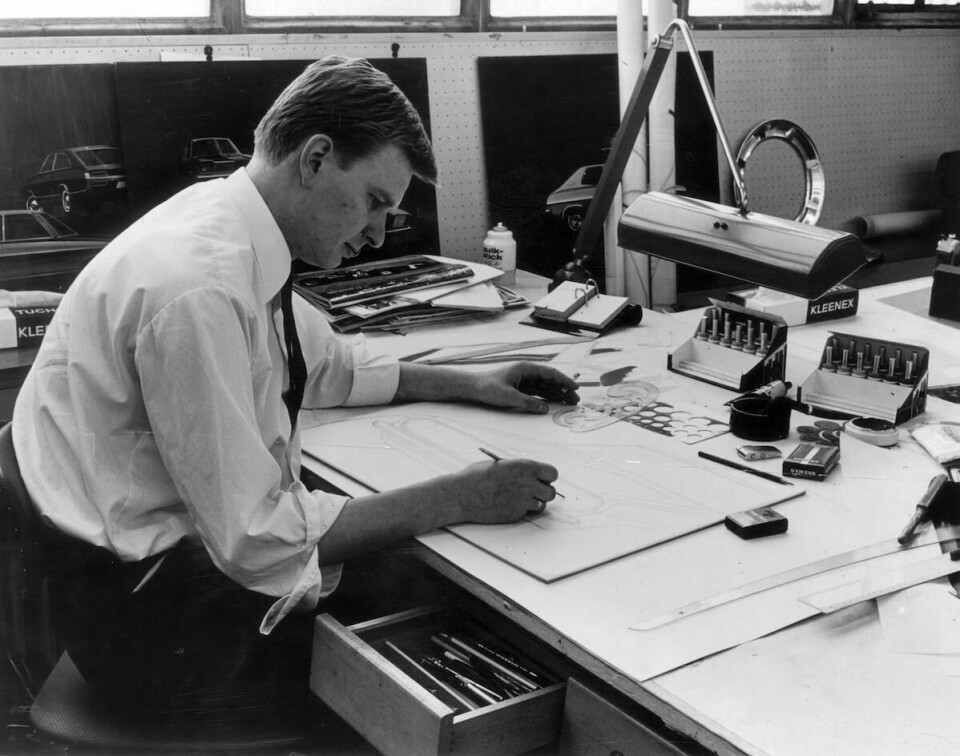

Warkuss was born on 8th June 1940 in Breslau, a city then on the far eastern edge of Germany which was besieged by the Soviet army at the end of WWII and renamed Wrocław afterwards to become part of neighbouring Poland. Warkuss seemed reticent about revealing any information about his early life here but VW records indicate that he started an apprenticeship aged about 15 as an engraver in Solingen, near Dusseldorf in the far west of Germany, from 1955 to 1958. He completed five semesters at the technical school for metal design and technology and after graduating there started his career as an automotive designer. Allegedly, he saw a newspaper advertisement for an industrial designer job at Mercedes-Benz in Sindelfingen, applied for it and gained an interview based on a portfolio of unspecified sketches. He is wonderfully self-deprecating about his reasons for winning the job there, stating only that “the hurdles were nowhere near as high as they are today,” and putting down his ability to reach the first rung of his future career ladder to a “winning personality” and a “drive to develop and implement ideas”.

Mercedes-Benz at that time was getting its design mojo back and had among its ranks the already well-regarded Paul Bracq and Bruno Sacco – the latter would go on to lead the design operation there. He saw them both as role models but in 1966 after only two years he moved to Ford of Europe in Cologne to work on both exterior and interior design and worked on a successor to the Ford 15 M (a German version of the Taunus). He quickly moved again in 1968 to Audi in Ingolstadt, where early success came in the form of the sporty 1970 Audi 100 Coupé S. He rose through Audi’s ranks to become lead exterior and interior designer by 1976 and was deeply involved in the 1978 Audi 80 mk2. After that he was instrumental in the now iconic rally-bred 1980 Audi Quattro and also the aero-inspired third-generation 1982 Audi 100 executive four-door saloon, which won the 1983 European Car of the Year. In that same year he became head of Audi design and went on to develop the smaller third-gen 1986 Audi 80 four-door compact saloon (penned by a young J Mays), the 1991 Audi Cabriolet and 1994 Audi A8 (mk1). All helped elevate the four-ring brand’s status in Europe and paved the way for its eventual premium carmaker status worldwide.

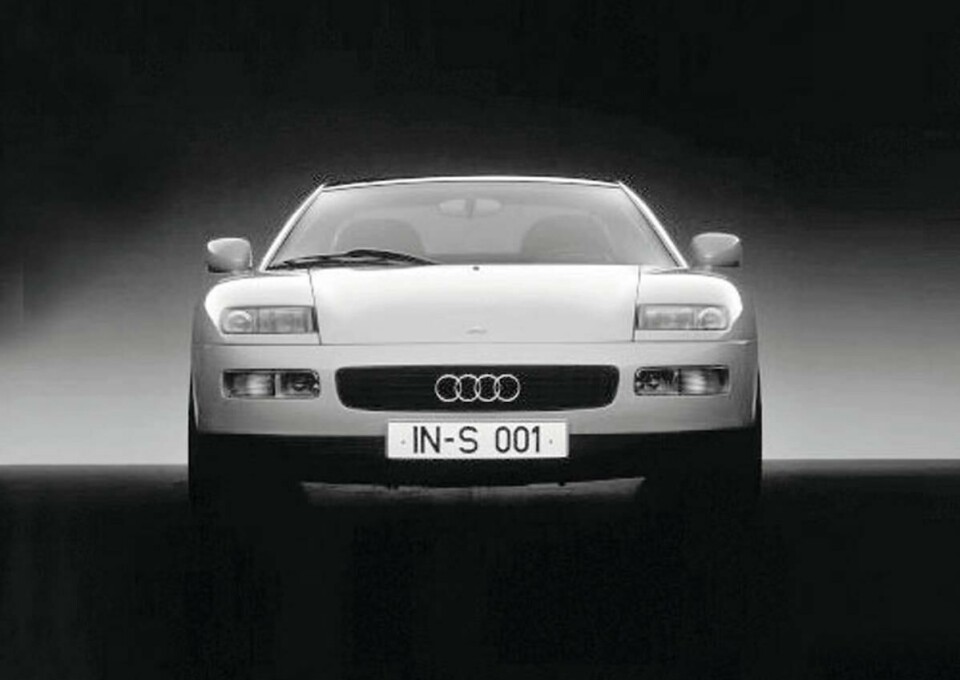

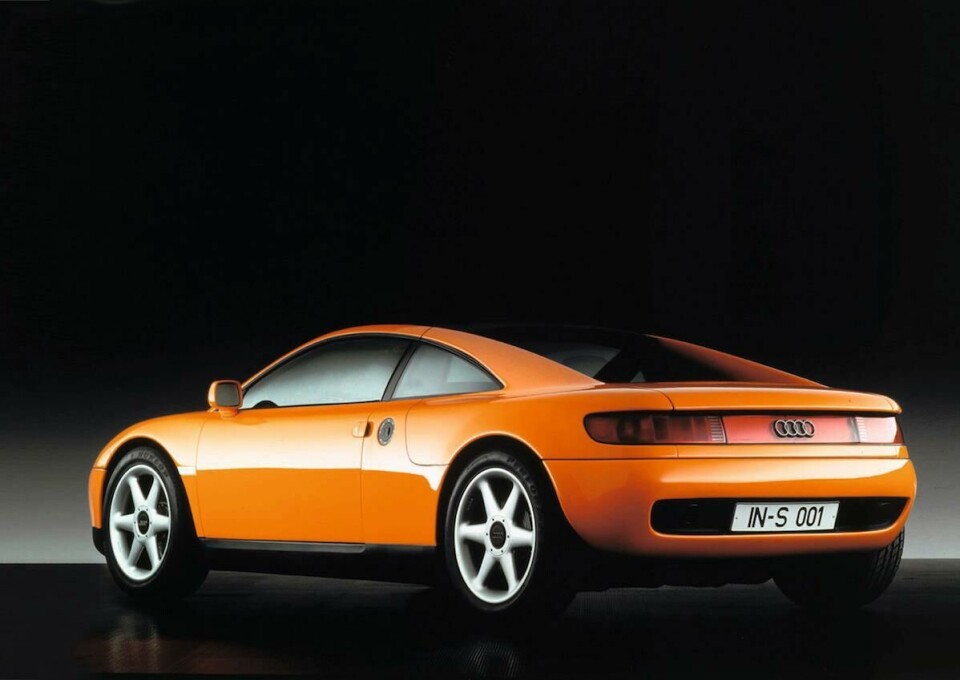

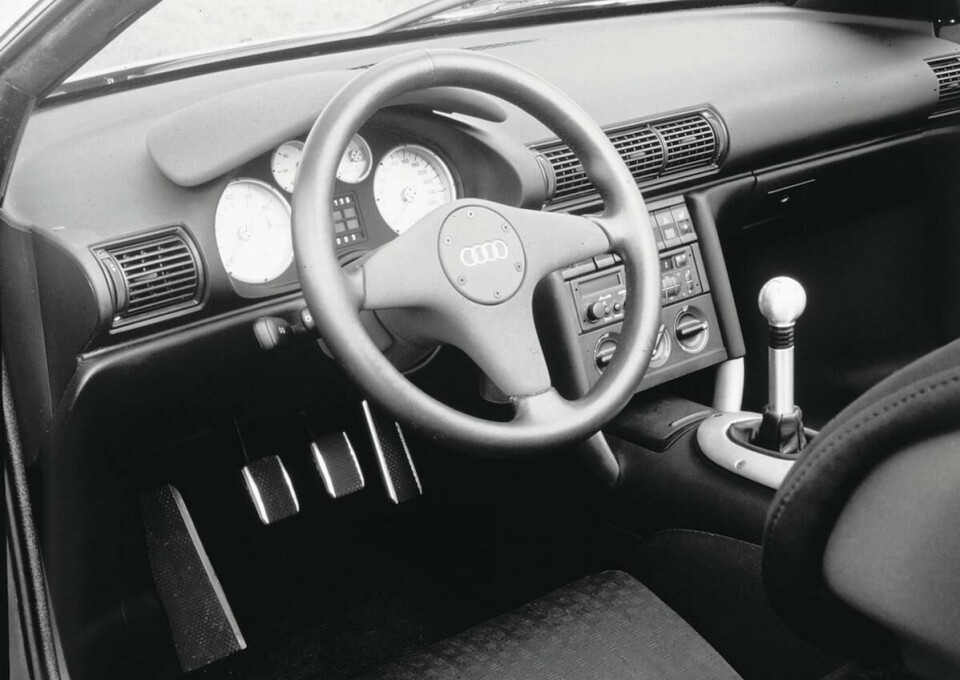

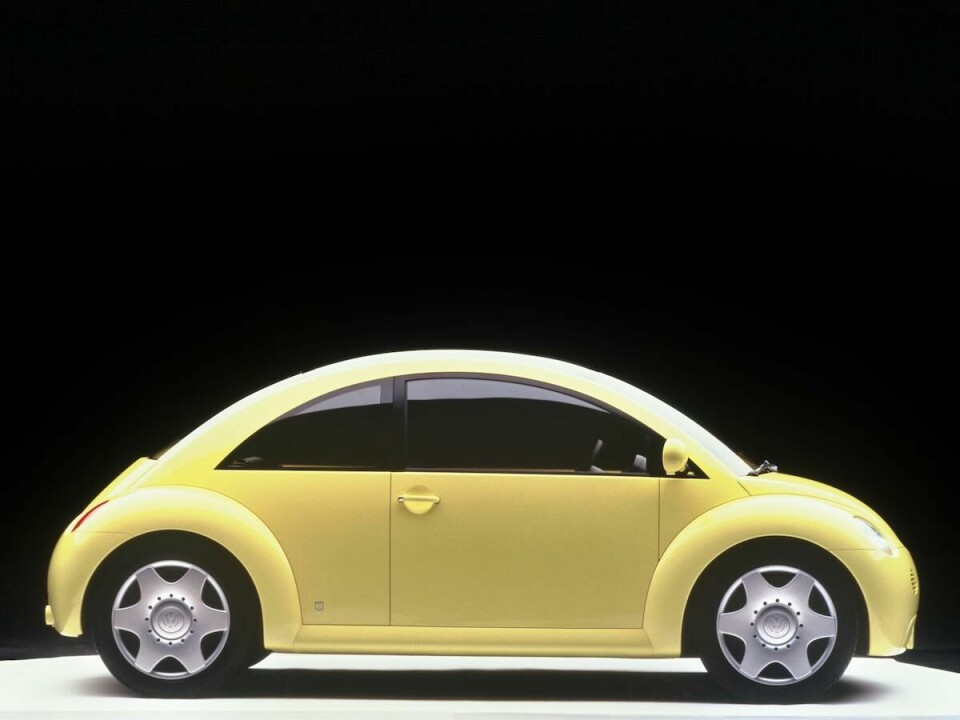

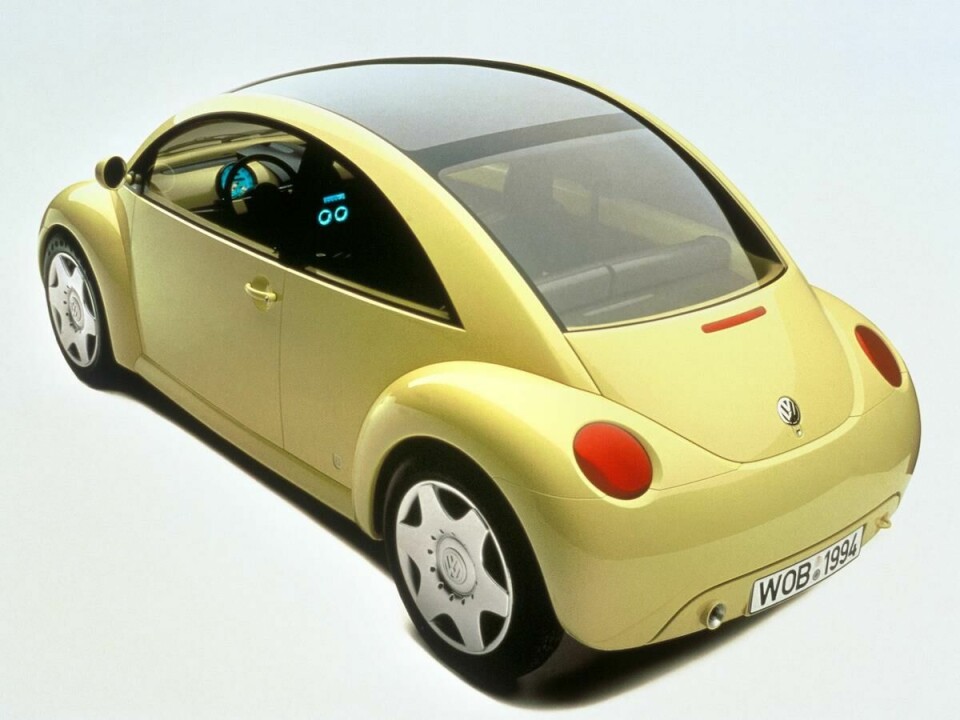

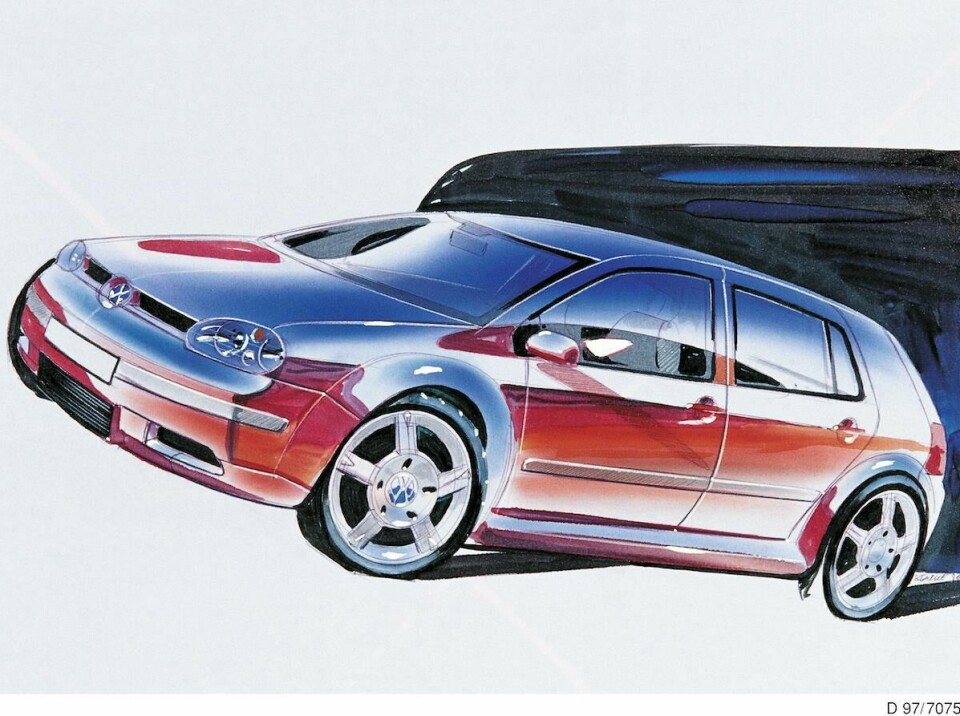

After more than a decade transforming the Audi marque – including key concepts like the 1991 Avus and Quattro Spyder – he became head of design of the Volkswagen Center of Excellence in Wolfsburg in 1994. There he oversaw the development of the new Beetle concept and production car, the 1996 Golf mk4, 1997 Passat mk5, 2002 Phaeton and 2002 Magellan concept which prefaced the brand’s first-generation Touareg SUV. Within that role he also worked on resurrecting the legendary Bugatti brand, culminating in the 1999 Bugatti EB 18/4 Veyron study unveiled at the Tokyo Motor Show and which led to the 2005 Veyron production car. In 2002 he took on the newly-created and much wider role of head of VW Group design before retiring in 2003. Now 80, Warkusskindly allowed Car Design News to photograph him in Wolfsburg earlier in 2020 and ask him a few dozen questions about his long career of automotive hits (and what he learned from the few misses) plus discover why a little relaxing flying goes a long way.

CDN: Many car designers say they remember drawing cars and perhaps planes when they were young. Was that true for you also, or did you have different artistic inspirations?

Warkuss: Aeroplanes have always fascinated me. In my youth and childhood, flying was nothing like as much a part of everyday life as it is today. At that time, planes were still somewhat uncharted technical territory. There was a huge variety of designs and shapes. What’s more, aviation suggested adventure and exoticism.

When you applied to work for Mercedes what car design experience could you draw upon? How did you convince them to take you on?

I applied to Friedrich Geiger, then head of design. I submitted a portfolio of course, that was standard practice back then. But in all fairness, I should also say that – unlike today – the shortage of existing training opportunities then meant there weren’t many automotive designers around. The hurdles were nowhere near as high as they are today. But one thing was as true then as it is now: you need a winning personality and a clearly apparent drive to develop and implement ideas.

Did you work alongside Paul Bracq and Bruno Sacco at Mercedes and if so, what kind of characters were they?

For me as a career starter, they were both great role models. I was particularly impressed by the fantastic sketches, renderings and paintings that Paul Bracq made. In my first few months at Mercedes I received a kind of basic training in automotive engineering. Rather than making design sketches, I learned to produce construction drawings of details. By doing this I established a solid foundation of knowledge, which was often helpful further down the line.

What was the design process at Mercedes like back in the mid-60s? What materials did you use to create production car prototypes then?

As is true of many makers, at that time Mercedes still created models in plaster. Although this was an involved process, it permitted a high level of precision.

Why did you leave Mercedes and what was your first role at Ford?

I was young, at the beginning of my career. More than anything I was curious and I wanted to get to know other companies and processes. Like all the American companies at the time, Ford was significantly advanced in its design processes. I was certain I could learn something there.

What were your early years at Audi and the VW Group like?

My job interview at Audi was with the legendary chief engineer Ludwig Kraus and I started there in 1968. The Group’s ethos at that time was nowhere near as distinct as it became 20 years later. Our objective was to advance the Audi brand and to make the leap to the premier league by applying both technology and design. This ambitious goal was unbelievably motivating. Throughout the company there was an inspiring atmosphere of optimism and amazing team spirit. I consider myself very lucky to have been a part of that. For design, what was needed to achieve this goal was not only a change in the design statement, but initially also the structure of a larger and more international team. We needed reinforcement in the form of new talent and it fortunately turned out that the Royal College of Art in London was just then expanding its activities in transportation design. Over the course of several years we recruited excellent up-and-coming designers from there, several of whom today occupy senior positions either with us or competitors. It was always a great joy to me to be able to promote the development of young talents and to see something grow. The atmosphere of optimism at Audi was shaped by Ferdinand Piëch, first as member of the board of management responsible for technical development, and later as chairman of the board of management. He set out demanding requirements for design, but also created excellent work opportunities for us.

What cars are you best remembered for and why?

The third-generation Audi 100 was our big breakthrough. It was the world aerodynamics champion and with it we laid the foundation for a new line at Audi. The first Audi A8 was another milestone and its design was a significant departure from its predecessor the Audi V8. The A8 represented Audi asserting itself in the luxury class and finally gaining a foothold there.

Have there been any car designs you were involved with that you’d rather forget? Cars that didn’t turn out quite how you wanted them to?

After successes with the original Quattro, the Audi 100 (C3) and its little brother the Audi 80 (B3), we perhaps took on a little too much when designing the Coupé. In any case, to my eyes the result was not entirely coherent. Nonetheless, it gave us a solid basis for the Audi Cabriolet, which established a successful model series.

Were there any lesser-known internal projects that you wish had made it to production at any of the brands you’ve worked at?

I always understood my responsibility as making an active contribution to the design in order to advance the company. By that I mean also developing my own ideas and getting them discussed, alongside the official development programme. One model of this type that unfortunately did not make its way into mass production was the Audi Quattro Spyder. I would have really liked to see that on the roads. There are also one or two models that disappeared into obscurity after the internal presentation. You have to be able to live with that. In any case, the work was rarely in vain because we developed our own skills in designing those products too, and indirectly also created impetus for later series-production projects. That’s why we were working on MPV- and SUV-type projects long before they went into series development. Sometimes, you have to wait until the time is right for a particular model. After all, despite being enthusiastic about new forms, as a designer you always have in mind that the model must also be worthwhile for the company.

However, one of our studies did make it straight into mass production: the Concept 1 study from our Design Centre in California became the New Beetle. It sold over one million vehicles, so our instincts were right there.

Throughout your career how did you perceptions of exterior and interior car design change?

Automotive design used to be very heavily focused on exterior design. In the 1970s, BMW turned its attention inward for the first time, producing a sophisticated interior design too and in doing so, it paved the way for a more conscious appreciation of the interior. At Audi, of course our aspiration was to make waves not only with our exteriors, but also our interiors. We wanted to underpin the ‘big idea’ of innovative interior design with very high-quality design details. We set a new standard in the industry by doing that.

Since the start of your career in the 1960s what changes have you noticed in the role of a car designer within a car company?

We were once seen as exotic outsiders and perhaps not always taken seriously as artists, but that quickly changed as design became more important to a product’s market success. At the same time though, the requirements for becoming a designer were increasing, in terms of the level of training and qualifications needed. Great steps forward were made in work processes, both in the design and model-building stages. It became a matter of course to secure a board of management decision on a new product with up to eight painted and transparent 1:1 models. So design became a key component of decision-making. In addition, designers are there throughout the implementation of the model up to series-production readiness, working in close collaboration with the engineers from the development and production departments. This supports not only the authenticity of the draft, but also the perception of quality.

How did the design cultures differ at the various brands you worked for during your career – Mercedes, Ford, Audi, VW and Bugatti?

My time at Mercedes and Ford was so long ago that my memories are really no longer relevant today. For each brand in the VW Group the design aimed to clearly and convincingly visually embody the identity of the brand. But not every brand has well-established, continuous development that can be built on. After several expansions of the Group, we got together in the early 1990s and used designers’ resources to create brand missions – design concepts that intuitively communicate the genes of a brand. These brand missions are not intended as simple instructions but they should serve to guide the designers and decision-makers in the company. Aside from the variety of concepts and associated interpretations, working methods are comparable across volume brands. At Bentley, Lamborghini and most prominently at Bugatti, smaller model ranges and an extremely demanding and exclusive clientele create something like an artisanal, craft-like culture, including design. I would also like to say about Bugatti that we treated this exceptional brand, which has such a glamorous and sporty history, with a great deal of respect. We went to extraordinary expense as we went about the implementation of the model for the rebirth of the brand. The company also sought advice from Giorgetto Giugiaro for this, who had previously participated in competitions with various models. In the spirit of sporting rivalry, it made us proud that we were able to win with our model against such a fantastic designer here.

Do you think you’ve influenced other car designers and if so, how?

It’s best to ask J Mays, Martin Smith, Peter Schreyer, Stefan Sielaff, Gregory Guillaume, Thomas Ingenlath, Marc Lichte, Jozef Kabaň or Klaus Bischoff about that. I was always drawn to finding and encouraging new and talented individuals. Every designer is different, there is no simple formula. The design team and I provide a framework in which a talented individual can develop their creativity. Sometimes patience is needed – I have to give a designer time to find their own way and support them while they do so. It has actually always been worthwhile. It’s never occurred to me to give designers strict specifications. I wanted to see what they could contribute in terms of their own new ideas. There is certainly a sense of achievement when the outcome is a model that I’m unreservedly impressed by. If I think back to when I was working, now, after 15 years in retirement, it is the progression of former colleagues that makes me particularly proud. To me, having been a part of that means more than any design prize for one of our models.

What’s your favourite part of the creative design process?

It’s the first phase: when individual, viable subjects crystallise from a multitude of drafts. When a team of designers presents its first drafts, there’s such an incredible liveliness in it. Each designer identifies with their own draft and wants to impress. I have always been particularly fascinated to read the essence from these sketches, which then takes on form in the third dimension.

You started your career in the pre-digital design age. What are your thoughts on modern digital tools and processes?

It’s nothing new for me. We took our first steps on computers in the 1980s, and the proportion of work performed on the computer increased gradually over the years. Even in my time at Wolfsburg, presentations of drafts created on the computer were given on a six-metre-wide projection screen known as a ‘powerwall’. Some designers preferred to work on the screen than on a sheet of paper. I don’t see the different processes as competing against each other. What counts is the result – and the time (taken or saved). After all, digital tools and processes help us to win time. Even in the past, models were milled based on data. But when it came to the final design, it was the eye and experience of the modellers that counted. This final polish and the opportunity to evaluate the model in real life and under natural conditions seems irreplaceable to me. I’ve heard that, despite all the progress in terms of digitisation, a real model is still preferred for evaluations today.

What do you think of 21st century car design, with its huge in-house teams at almost every brand?

Experience has shown that an in-house design department understands the brand more easily, enabling it to work more efficiently. Communication between the departments is more intensive. And if the brand has a wide-ranging product portfolio, the design department also has to be correspondingly large. I don’t see a problem with that – it’s a question of structure and organisation. For example, I set up small teams that were as independent as possible, on a case-by-case basis and had good experiences with that.

How do you see the future of the car in society? Do you think cars will even be called ‘cars’ in 30 years’ time?

The critical consideration of mobility is really not so new. It’s always been essential for us as designers to be aware of societal change. The importance of some forms of mobility will change. A new understanding of mobility will also shape automotive design. With a team of designers that is getting younger all the time, I’m confident that in the future, solutions will also be found that bring together individual mobility with a high degree of social acceptance. And if I know our designers, there’ll be plenty of emotion in those solutions too.

What advice would you give an aspiring car design student wanting to get into the industry?

Designing an automobile demands the ability to create a design that is self-contained and to see the shape as a whole. The shape should radiate harmony from every angle. However, each individual should critically review whether his – or her – talent is enough and then believe in themselves and work hard. In practice, the capacity for teamwork is essential. Commitment pays off because in transportation design, there will also be plenty of room for development and successes in the future.

Do you think car designers today need different skill sets than when you started out?

Creativity and the will to succeed are still prerequisites and equipped with these, a designer can take on the challenges ahead. I would add the presumption that they need to master current work techniques too. I’ve deliberately included female designers in my previous answer as I’m convinced that including a greater proportion of female creativity in the future will be an advantage.

Which car do you wish you had designed?

Particularly given the historic context of the company’s situation at that time, the design of the VW Golf mk1 was very courageous, but also pioneering. Giorgetto Giugiaro created many design icons, but the first Golf moves me because we engage with the original every six or seven years when designing a worthy successor.

…And which one are you glad you didn’t?

I’d like to provide an indirect answer to this question. For the majority of my professional life, I held a management role where I was responsible for design. In that position, I found out how closely a product and the company’s culture are connected. I believe that I would not have been happy at an American or Asian brand.

What is your favourite non-car design?

Aviation is my great passion. The Schleicher ASW 15, designed by Gerhard Waibel, is my favourite sailplane. The greats include the Lockheed Super Star Constellation, which is rightly considered to be the most beautiful passenger plane of the 1950s.

Away from cars, what do you do to unwind?

Nothing relaxes me as much as flying. Sitting at the controls of a sailplane or single-engine aircraft is an incomparable experience for me.

This article first appeared in Car Design Review 7.