Chris Bangle on the 50th anniversary of BMW’s Four-Cylinder Tower

As the Bavarian brand celebrates a milestone, the former BMW design director talks details with CDN’s North America correspondent Laura Burstein in this exclusive interview

We at CDN celebrate cars on a daily basis but, of course, we also often look to architecture for inspiration. As with the vehicles we drive, the structures in which we live and work are significant beyond aesthetics; they can be symbols of our values, our culture and our aspirations for the future.

In the late 1960s, BMW was enjoying renewed growth after narrowly escaping bankruptcy and acquisition from Daimler-Benz less than a decade earlier. The company had turned its attention from making expensive, big-engined sports and luxury cars like the 507 to a line of more attainable saloons and coupes. Starting with the Neue Klasse and followed shortly thereafter by the more affordable 02 Series built on a shortened New Class chassis, BMW was gaining ground with not only European customers, but those in America, too.

Over the next years, the company produced several models, including the 2000 CS and 2002, with design led by Wilhelm Hofmeister – as in BMW’s signature rear window kink. A growing workforce meant more office space, and in 1966 BMW began the search for designs for a new administrative building in its already-dense neighbourhood of Schwabing in northwestern Munich.

At the same time, Munich was planning to host the 1972 Olympics, a symbolic welcoming, of sorts, of Munich and greater Germany back into the global community after the atrocities of World War II. “That whole time period was very important for the nation as a whole and they looked toward Munich,” Chris Bangle, the brand’s chief of design from 1999 to 2009, told us. “In those days, BMW had already been making a name for itself with product. American money was starting to flow, and in terms of corporate branding, BMW really began to put its foot down on the accelerator pedal. And with the Olympics coming to Munich, they had to figure out how to make the building really quickly.”

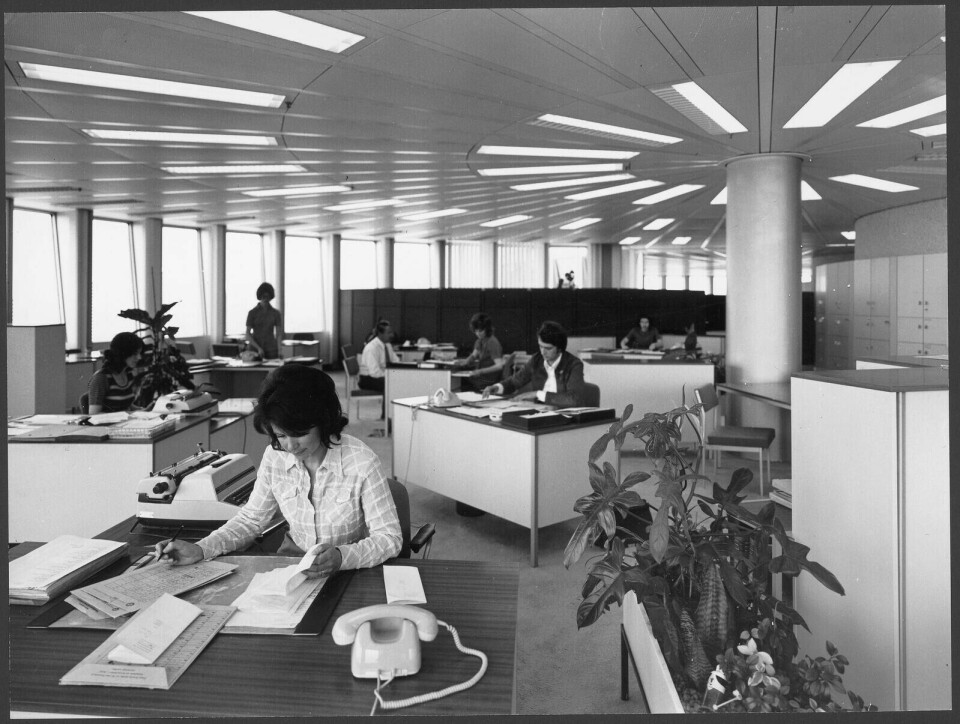

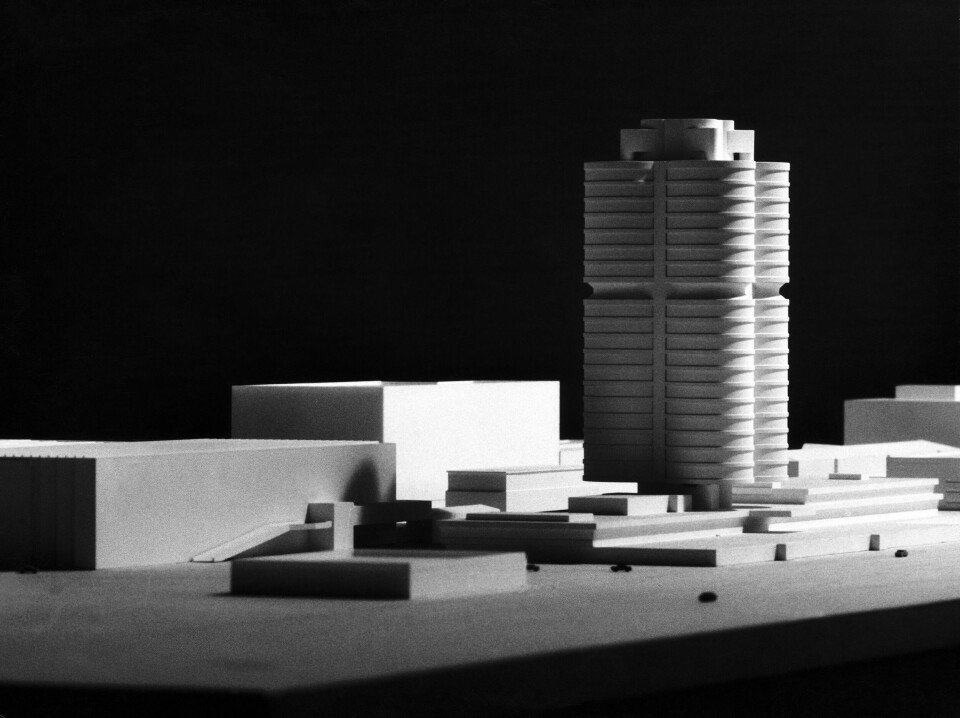

BMW executives put out bids for the new building and narrowed it down to two choices: A conventional “seven-storey high-rise block” and a proposal by Viennese architect Karl Schwanzer, an imposing, near-100-metre tower with four cylindrical elements that would appear to float, suspended from above. Not only was Schwanzer’s design head-turning, but, he asserted in his pitch meeting, the cloverleaf-shaped floorplan created open, circular office space that encouraged collaboration and reduced distraction, with the elevator banks (and therefore foot traffic) confined to the centre core.

Schwanzer’s cause was helped by BMW sales director Paul G. Hahnemann, nicknamed “Nischen-Paule” or “Niche Paul,” for insisting that the company’s portfolio contain a vehicle that filled every niche. Hahnemann recognised that brand identity could reach far beyond the products a company made, and helped to convince others at BMW that theFour-Cylinderwould become an iconic symbol of BMW’s – and Bavaria’s – success.

The 21-storey building consists of 18 office floors and four technical floors. Each cylinder contains a concrete shear core for stability as well as vertical ties and compression columns that run along the exterior façades. The indented level visible near the top third of the structure consists of trusses that transfer loads between the columns and the cables.

You can’t deny that the four-cylinder looks like an engine, with these spinning, turbine-like gears

BMW reference materials explain that the four cylindrical elements were initially constructed at ground level, before being raised hydraulically and completed in several segments. Each cylinder was suspended from four giant “crane arms” positioned in the shape of a cross at the building’s central core. Many of the elements were pre-fabricated, saving time and money.

“You see that spacer [the indented level]? Basically they built the top stack first and hauled the whole thing up, then added one floor at a time underneath the other as it went up,” Bangle says. “It saved them a shitload on scaffolding and things like that. It was pretty clever.” Not only was the tower a technical achievement, the entire project was completed in only 26 months.

The architects at the outset didn’t necessarily intend for the tower to look like the cylinders of an engine, but the parallel was an obvious one to draw for an automobile manufacturer, and it wasn’t long before it was colloquially dubbed the Vierzylinder. “You can’t deny that the four-cylinder looks like an engine, with these spinning, turbine-like gears. It’s very technical,” Bangle explains. “I think that’s completely fitting for an engineering company. It’s not a Bavarian car design company, it’s a Bavarian Motorwerke.”

Alongside the Four-Cylinder, Schwanzer also built a futuristic-looking parking structure, and the bowl-shaped BMW Museum, which still welcomes guests today. “When it opened the museum was a shell with a spiral ramp in it. Nobody had ever seen anything like that since the Guggenheim,” Bangle muses.

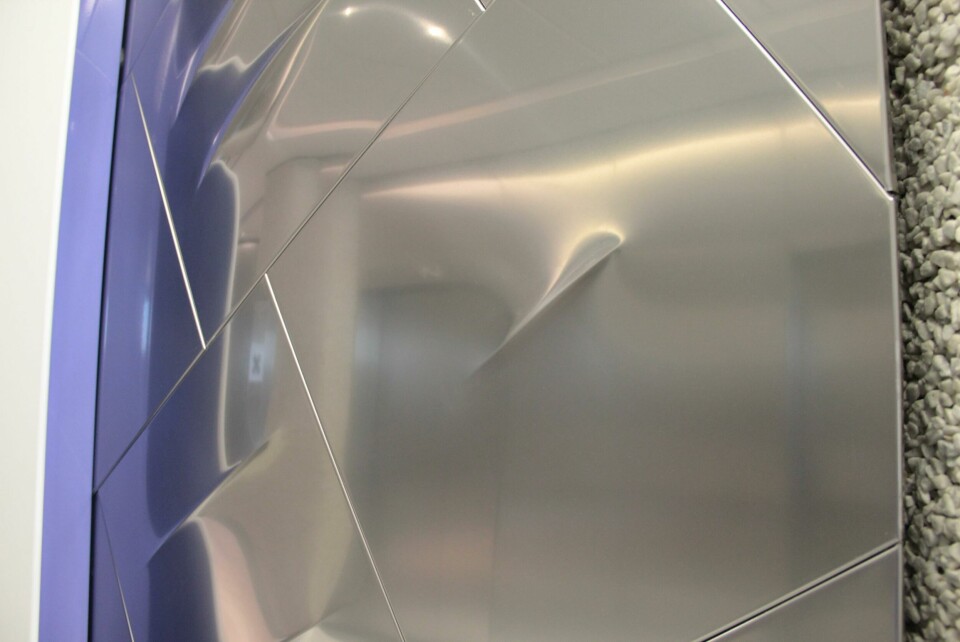

Although Bangle hasn’t been with the company for more than a decade, his time and position as the chief designer for the group that encompassed BMW, Mini and Rolls Royce puts him in a unique position to comment. During his tenure, in the early 2000s, the Four-Cylinder went through significant renovations. As part of the changes, two elevators were removed to make way for a larger fire elevator, a reconfiguration that left a blank wall space on every floor. Bangle was asked to come up with some artwork to fill the void. Helmut Panke, then BMW’s Chairman of the Board of Management, had some strong opinions of what those “wall decorations” should look like.

“Panke said, ‘I want anyone to know where they are in the building because it makes each floor unique in some way, I want it to reflect the latest in technology we have to offer, and I want it to reflect our workforce and the way we make our cars,’” Bangle remembers. His resulting creation was a combination of custom-made metal pieces, car parts, and coloration that varied between floors. “I came up with a set of GBK – ginableschkleid – this was how we formed the hoods on the M Z4. It uses a robot to actually shape the metal, not stamp. I had the robot shape individual pieces of stainless steel, so there’s hundreds of them going up into a shape diagram that’s different on every floor.”

Bangle also took Panke’s advice about “reflecting” literally. “I took the aluminium hoods from our cars, had them polished up to a mirror, and put them inside of a frame, so you see a mirror of yourself,” Bangle explains. “From the side, you can see a color spectrum that runs from red to green one way and green to red the other way, but different reds and greens. So depending on what the hood is and what color you see, you know what floor you’re on. Each one is different but made with the same pieces. And you reflect the workforce and the worker in it. I was actually quite proud of it.”

Also during Bangle’s time, the campus saw the addition of the BMW Welt, a flagship showroom for the group’s cars, motorcycles and branded merchandise, designed by Wolf D. Prix at Coop Himmelb(l)au, also based in Vienna, as with Schwanzer’s erstwhile architecture firm. Complete with a two-Michelin-star restaurant at the top, the Welt, during pre-pandemic times, saw three million visitors every year. “Compare the Vierzylinder with the BMW Welt, which is supposed to be more avant-garde for its time. As a side note, [the Welt] was always frustrating to me as a designer because the curves are a horror story. They just are not in order.”

It’s very sophisticated, the relationship between the park, the building and everything else. It makes you proud to work at BMW

But BMW isn’t done expanding. The next project slated for the complex at the Petuelring is a transformation of the Werk 1 assembly plant, which will be converted to build BMW’s next-generation “Neue Klasse” vehicles on a new, electrified architecture. Spokespeople for the project say the renovated factory will not only be more sustainable, but will lend a more open, transparent feeling to the space for its 7,000 employees.

Meanwhile, the Vierzylinder continues to stand today as not only a testament to BMW’s corporate branding prowess, but as a reminder of Munich’s rise to one of the world’s great cities. “In a symbolic sense, it was like the rebirth of Germany and the return to the German precision product as being world-class,” Bangle explains. And then if you look at the Olympic structure across the way, it matches really well. It’s very sophisticated, the relationship between the park, the building and everything else. It makes you proud to work at BMW.”