Metasketching: an interview with Mike Jelinek

Mike Jelinek is an artist, designer, and researcher practicing in Czechia near Prague. He has a strong automotive design background having worked with Škoda, Volkswagen, PSA, and General Motors Europe. Jelinek spoke to Car Design News about advancing the next generation of design tools via his work at Wacom

Mike Jelinek is an artist, designer, and researcher who has also worked extensively with computer software for the design professions, having worked with Autodesk, and currently with Wacom, advancing the next generation of design tools.

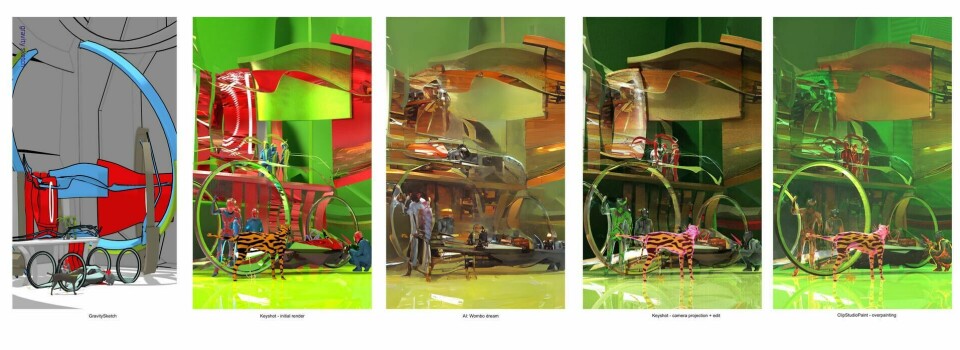

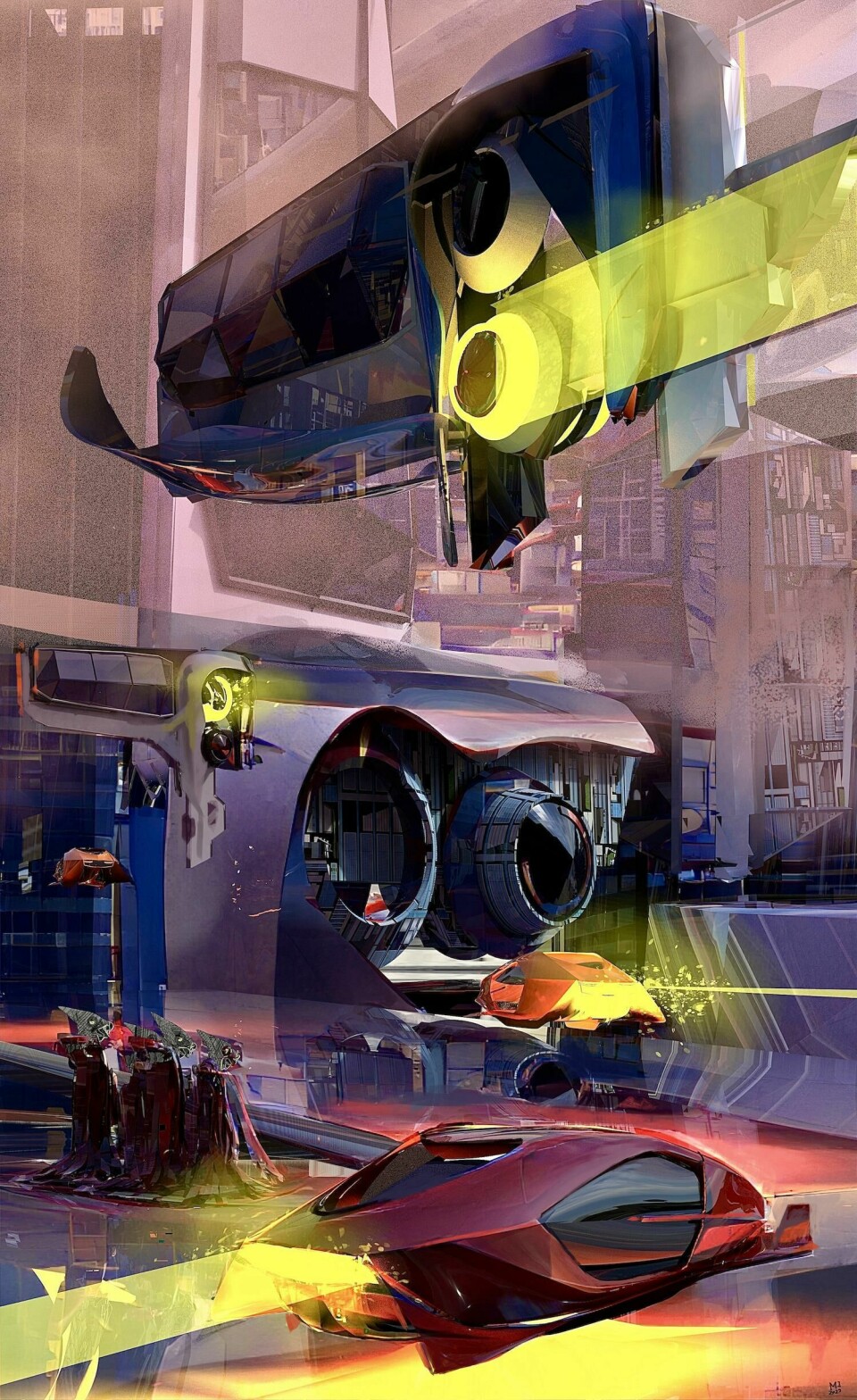

Although much of his work at Wacom is top-secret, Jelinek agreed to sit down with us and discuss his research into sketching, ideation and human perception. Much of this research is revealed in his “Metasketching” project, which looks beyond traditional sketching to new concepts of ideation. An exhibition of his “Metasketching” project is currently on display at University of Western Bohemia through June and will then travel. The galleries pictured here show some of his work and the process.

Below is a lightly edited version of our conversation over Zoom:

Car Design News: In your doctoral studies you have done extensive research into sketching ideation, and cognition. Is there one thing that you would like designers to know from your studies, what would that be?

Mike Jelinek: The process of creation and ideation is deeply connected to our bodies. We literally think with our bodies. When we sketch, we use our hands and arms to create something, but we can do much more we can describe scale and size and more by a wider range of gestures. That’s why VR technologies make so much sense in the design process today.

As part of my PhD research, I have conducted workshops at universities across Europe. At a recent workshop in France, I conducted a design workshop, and for the first four hours we did not pick up a pencil and paper. Instead, we used words and gestures to describe our vision of the product in the design brief, what it looked like, what it was on the interior, what was its skin, what are its openings, how one interacts with the product.

Words and gestures dominated the session, with students using fingers and hands all the way up to moving chairs around the room to simulate movement. The students saw that design can be a whole-body activity, something beyond a sketch on paper.

We have all seen designers who became so accomplished with a tool that they became trapped, and that tool influenced their design and presentation ultimately to their detriment.

CDN: Please explain to our readers what you mean by “Metasketching”.

MJ: I have learned that ‘sketching’ is way more important to humanity than we previously believed. A professor of cognitive psychology opened my eyes when she called sketching literally “thinking on paper. The externalisation of the thinking process.’ Think of simple addition of five or ten numbers. It is much easier to add them on paper that in our minds. Externalising the process helps augment our mental processing capacity. Sketching works in a similar way not only illustrating an idea, but helping us think through the problem. Sketching goes beyond art, beyond designing, beyond illustration. That’s while I use the word “Metasketching” meta from the Greek meaning ‘beyond’. Think of ‘Metaphysics’ – beyond physics.

CDN: What are the essential ideas of ‘Metasketching’?

MJ: Firstly, stay away from delivery. As designers we are trained to focus on delivery, of producing a design and delivering a beautiful presentation drawing. But the more you focus on delivery, the less creative you are. We should ideate and explore as long as possible, using divergent thinking to seek new ideas. Execution and delivery are convergent thinking, focusing on achieving the goal. Secondly, embrace ambiguity. Ambiguity is our friend, especially at the very core of the ideation stage. Thirdly, interact with our design- rotate it, take it apart analyse it piece, look at options.

This leads me to the MetaSketching Manifesto:

- Obey the Ambiguity

- Explore and Interact

- Let Slip the Artifact

CDN: In addition to the traditional techniques, new digital tools are entering the designer’s studio all the time. Mastering these tools is quite a challenge in itself. Is there any chance that these new digital tools could limit the exploration and ultimately execution of a design?

MJ: Both scenarios are possible. The new generation of digital/VR/AI tools can enormously expand the whole creative process. But it could limit it as well. I have a saying, “The Tool Rules”. We have all seen designers who became so accomplished with a tool that they became trapped, and that tool influenced their design and presentation ultimately to their detriment.

This could happen with any tool, digital or analog. And the way you approach a work of art does differ depending on the tool. An artist would approach a painting quite differently if handed a house painting brush as opposed to a fine Indian sable brush.

It might be a little far-fetched to foresee a day when a design goes directly from a designer’s computer to the production floor but it isn’t beyond the realm of possibility

Certainly, digital tools have one huge advantage over traditional ones: The ‘undo” command. This gives us enormous flexibility and allows for mistakes- mistakes from which we learn and grow as designers. Ultimately, it is about opening ourselves to the potential and the appropriate placement of tools in the process, whether digital or analog.

CDN: Might the design studio of the future, embracing the sketching process as one of a whole-body movement, transform itself into something more akin to a ballet or martial arts studio enabling whole body movements as part of the design process?

MJ: It is possible, at least in part. Certainly, new tools like Gravity Sketch cry out for a dedicated space, and future tools may demand even more.

That said, speaking in to one’s self and doing wild movements might be a bit unnerving to your fellow designers and could be a big distraction in a studio environment. Some balance of the individual design space and more whole-body design spaces will need to be developed. I believe we are not too far from this scenario. Also, the design of the studios should reflect the design process and tools used. Some may use VR tools extensively, while others may follow a more traditional approach.

CDN: Speaking specifically about automotive design, what possibilities might be opened up by the implementation of this new generation of tools?

I think the greatest opportunity lies with opening up the creation process. For decades we have had a standardised and rather linear creation and production process. But often design advances and discoveries are made deep into the design process, and it can be expensive to backtrack and repeat or recreate a design that seemed fully envisioned. With digital tools the process is more circular and can still advance forward.

We can envision in VR like Gravity Sketch, and then develop this and feed the design into a rapid prototype machine, evaluate and then revise or fabricate finished designs via advanced 3D printing and milling techniques. It might be a little far-fetched to foresee a day when a design goes directly from a designer’s computer to the production floor but it isn’t beyond the realm of possibility.

CDN: How will the introduction of Artificial Intelligence affect the ideation and design stages of automotive design? Will it be positive or negative (or both)?

MJ: A.I. certainly holds the possibility of opening up an enlarged ideation stage – I’m thinking of the ‘mood board’ or ‘vision board’ stage. There are possibilities at later design stages as well. Many designers think this could be the end of their careers. But actually, it opens new positions in design fields of all types. With A.I. doing some (or much) of the work, designers move into the “Art Director” position, curating the work of the artificial intelligence and directing the work, developing promising concepts, managing prototyping, and many other tasks that require human knowledge. There will be more design jobs in the future because of A.I., not less.

To learn more about Mike Jelinek, please see his website at: www.horseville.net