Q&A with Antony Villain, Alpine

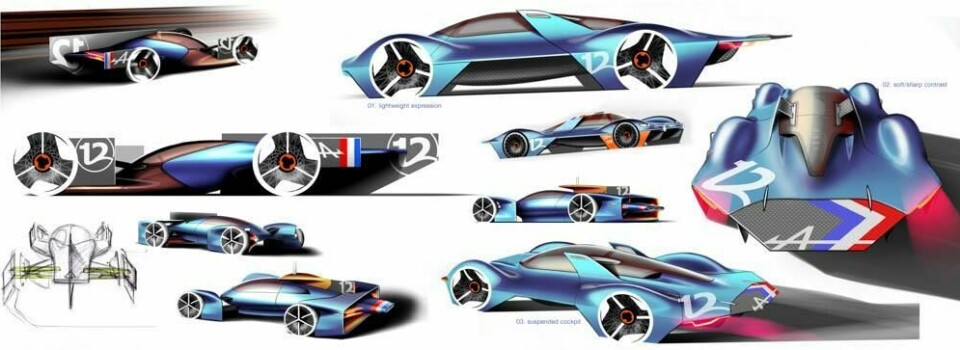

Alpine’s first production car for more than 20 years is set to launch at the 2017 Geneva motor show. CDN talks to its design director, Antony Villain

The resurrection of Renault’s racing brand Alpine has been something of a slow process. Although the first standalone production car since 1995 doesn’t go on sale until later in 2017, it has had a dedicated director of design – 42-year old Frenchman Antony Villain – since December 2012.

Villain is a Renault man through and through, joining the French marque back in 1998. Early examples of his work include race cars (2000 Formula Renault and 2003 Formula Renault V6), concepts (2003 Bebop and 2005 Zoe City Car) and production cars (2008 Laguna Coupe). By 2005 he was design director of innovation and in 2009 rose to director of the small car programme, overseeing the full design development of the highly successful 2012 Clio mk4 and 2013 Captur models.

In April 2011 he took on the broader role of design director of ‘studio exterior one’ before moving to his current position as Alpine’s director of design at the end of 2012. In charge of the sport brand’s recent concepts after the initial 2012 A110-50 showcar (which Laurens van den Acker oversaw before Villain took up his current role) and its crucial forthcoming production car, he chats with Car Design News about his career, aero and architectural inspiration and Alpine’s tricky rebirth.

What were your early influences that led to your career path?

Aged 10 or 12 I went with my father to racing events like the Grand Prix de l’age d’Or and remember seeing the 1923 C6 Voisin Laboratoire. It was a shock. Designed by an engineer who was used to designing planes [Gabriel Voisin] it used a lot of aluminium, had a narrow track at the rear and was very modern. My dad was an enthusiast. He owned a 60s Panhard CD Rallye, it was very aero and tiny.

When did you start drawing and making your own cars?

I drew everything, planes, cars and boats but wanted to turn my sketches into 3D. So when I was 14 I made a car sculpture with my dad’s help. It was a 1:5 scale model based on a Ferrari Testarossa package chipped away from a plaster block. It was a mess, plaster went everywhere so my mum was not happy [laughs]. I made a second 1:10 model when I was 15 or 16 which was more freestyle and all by myself. I still have them at my parents’ house. I went to the Paris motorshow with photographs of my sketches in an envelope and gave them to a really important guy in my career, Michel Jardin. He was in charge of advanced design and concept cars at Renault. He asked me to visit him in Boulogne-Billancourt. It was the first time I saw real designers’ sketches. I met him every year for four or five years. At that time there were not so many jobs, but he said, ‘keep on working at school and sketch as a hobby’. When I needed an internship at my engineering school I chose something more design-oriented. My second internship was with Mr Jardin, where I didn’t learn engineering, just sketching.

Were your engineering tutors okay with that?

When you do your internship you have to learn process and management too so I was honing my skills and in parallel learning about the organisation. I did mechanical engineering and then entered the army for my National Service. I did a shorter 10-month stint and then Mr Jardin hired me. It was unexpected as car design was more of a hobby, my skills were in engineering. But it was my dream. I learned with the Renault design team, first with magic markers and clay, and then with computers.

What were the first significant projects you worked on?

The 2000 Formula 1 Renault and 2003 V6 and World Series racing cars, as they were kind of engineering and aerodynamics. I learned about innovation and perspective from working on concept cars, including the 2003 BeBop small SUV and the exterior of the 2005 three-seat Zoe City Car concept. I was also a project leader on the 2008 production Megane mk3 and Laguna Coupe production car launched in the same year. When Mr Jardin retired I took his place.

Did he recommend you, or did you take his job?

I don’t know, a bit of both [laughs] it was good timing. I worked on the Twizy and other concepts. I did a full-size mock-up of the Twizy in white foam and it’s exactly the car that was finally created. It was really basic stuff, two frames of wood, the foam in the centre and four wheels.

How did your involvement at Alpine start?

I was working on the small car programme – the Clio and Captur – when Laurens van den Acker arrived [as design VP of Renault Group design]. We had a bunch of mock-ups ready and he fell in love with one of the Clio designs. We have a good relationship, the same mindset. I think that’s why afterwards when we started Alpine he asked me to take care of the project.

Alpine is a tough brand to resurrect, it means something to a few people but nothing to many others?

Every two years in design we’d propose a new Alpine project to management. The brand exists today because of the design department and [then Renault COO] Carlos Tavares. Before it was not possible because Renault was pretty weak, but once the Clio and Captur succeeded we thought it was time to resurrect Alpine. It was a design initiative.

When was the last Alpine production model made?

It was the A610, a dedicated rear-engine sports car sold until the mid-90s.

Given its chequered history and such a big gap in time, the weight of expectation must have hung heavy on your shoulders?

Yes, and as you mentioned, there were two things: In France everybody knows about Alpine so they were waiting, waiting, waiting, but for most of the rest of the world, it’s unknown. There are some enthusiasts in Japan, Australia and South America but very few. Only 30,000 cars were made in 40 years. In late 2012 Renault signed a joint venture with Caterham to develop a new sports car but for some political reasons we split with them [in 2014].

The classic A110 seems a big inspiration for your recent concepts?

Yes, because this is the iconic car that won the World Rally Championship in 1973. It beat its more powerful competitors because the car was lightweight, with a small engine and rear-wheel drive. That was DNA of the brand. That’s why we decided to stick with the A110. Whereas, the A610 Le Mans edition was heavy and powerful. It was losing its mind, its DNA, that’s probably why Alpine died back then. The name Alpine, comes from driving over the Alps, and really enjoying driving in small turns, so it was about these ideas: Good agility and power-to-weight ratio.

In budget terms, were there design solutions you could afford on the forthcoming Alpine production car that you couldn’t on a Renault?

Yes, it’s a premium marque so we have to get to the right quality level.

Achieving that production quality must be quite tough though as there’s nothing in the Renault Group with that level is there?

The big chance we had is with the Dieppe plant – the historic factory for Alpine and where the A110 was built – and where all the RenaultSport derivatives like the Clio and competition cars are made. So there is a know-how for making low-volume sports cars and we are going back there. It’s a flexible plant where we can set up such quality. Especially on the interior, we have really tried to emphasise the technical parts. Instead of covering things we decided to show the structure. We use a double-clutch so we don’t have any mechanism underneath, and we try to put the leather exactly where there is contact. So it’s lightweight, you highlight the design and go to the essence. We think there is an elegance to this approach.

The business plan to sell the Alpine as a circa £50,000 car to compete against Porsche seems very ambitious?

In fact, there are not so many competitors. Porsche is much more about power and luxury on a higher level. Then you have track-oriented cars from Lotus and the Alfa 4C, but in-between there is nothing. If you can create a car which is light, agile and pleasurable to drive with good materials which is usable everyday, not only on track, I think there’s a role for Alpine to fulfil its heritage and its ‘French-ness’.

Which designers were involved in the early Alpine models?

I think the process started with designs by Giovanni Michelotti and then a young guy in Dieppe in the late 50s and early 60s called Philippe Charles. He created Alpine’s A logo with the arrow and it’s really nice, so we kept it. We talked a lot. It was pretty interesting to see how they worked back then, not to imitate it today, but to get close to their mindset. Of course it’s a different time but we tried to go very fast, that’s why we spend a lot of time with the racing team as everything they do is oriented towards action. Sometimes in big companies this speed is something you can lose. A small team focused on action is the way I prefer – from a physical mock-up then quickly to prototype, and then to develop the car directly. We are based in Renault’s Technocentre but we have a dedicated workshop and our own door!

Seeing so many Alpines together at Goodwood 2016 I couldn’t get over how tiny they all were. Is it hard to keep the essence of the brand in the bigger vehicles demanded by today’s safety legislation?

There is a certain elegance in the 1977 A110 and one from the late 60s that binds them. Alpine was never into arrogance, they were pretty pure and elegant. It had a really unusual proportion, looking almost the same from the front as from the back. The rear is really low and the wheels pop out from the bodywork. We wanted to keep these attributes as they’re unique. In particular, I really like the original shape A110 Berlinette – its front end with the four headlamps is characteristic of Alpine – plus the pure arrow shape of the front, the proportion of the wheels to the body and this low diving line that makes the car seem very streamlined.

What are some of your personal inspirations?

Many of us at Renault are inspired by aeroplanes and we have since co-published a few books of plane designs called Speedbirds. Planes are nice examples of good engineering: things are functional and have great design without having to have styling cues. 1950s architecture too, like Richard Neutra, are among my personal inspirations. His approach was very pragmatic and essential; Le Corbusier too. In car design, I like a lot of designs but not any one designer. I’ve sketched all the old Alpine cars to understand them better.

Which car do you wish you had designed?

I really love the Jaguar CX-75 concept, the one in the James Bond film Spectre. When I was a kid I was really keen on the XJ220, it’s kind of a concept car for the road. The C-X75 is similar, even though [in the end] there was no production version. The car I prefer above all is the [Pininfarina-bodied] 1954 Maserati A6 GCS Berlinetta. It has the best proportion ever and it was a pleasure to see one at Villa d’Este in 2016.