The celebrity railroad designers by Peter Stevens

Peter Stevens examines how design defined the railroad expansion of the 1930s. What can car designers learn?

The 1930s was a great time for the expansion of railway systems across the world. Air passenger transport was just starting to become a possible alternative but it was expensive and the range was still limited by ‘fuel capacity versus weight’ equations, which meant that it was not possible to offer the quality of service that trains could offer.

Speeds for passenger trains were rapidly climbing, a fast service demonstrated modernity and pointed to an ever-faster future. Most rail systems were state owned at this time, but the big exception was America where competition between privately owned rail companies was intense.

Particularly in Europe, there was a competitive element between the state-owned systems of different countries, to have the fastest trains was becoming a question of national pride. Speeds of over 160km/h (100mph) were quite possible and ‘streamline’ styling was a good way of demonstrating both modernity and high-speed efficiency.

Aerodynamic efficiency was not actually that important for a train weighing hundreds of tonnes; the basic form of a train is quite effective as an aerodynamic shape so it was not until much higher speeds were attained that the shape of the front became important. But ‘looking modern’ was very important.

The competition between the major rail companies in the US caused an explosion of creativity in the style of not just railway locomotives but entire trains; design consultants were engaged to reinforce the futuristic messages of the companies.

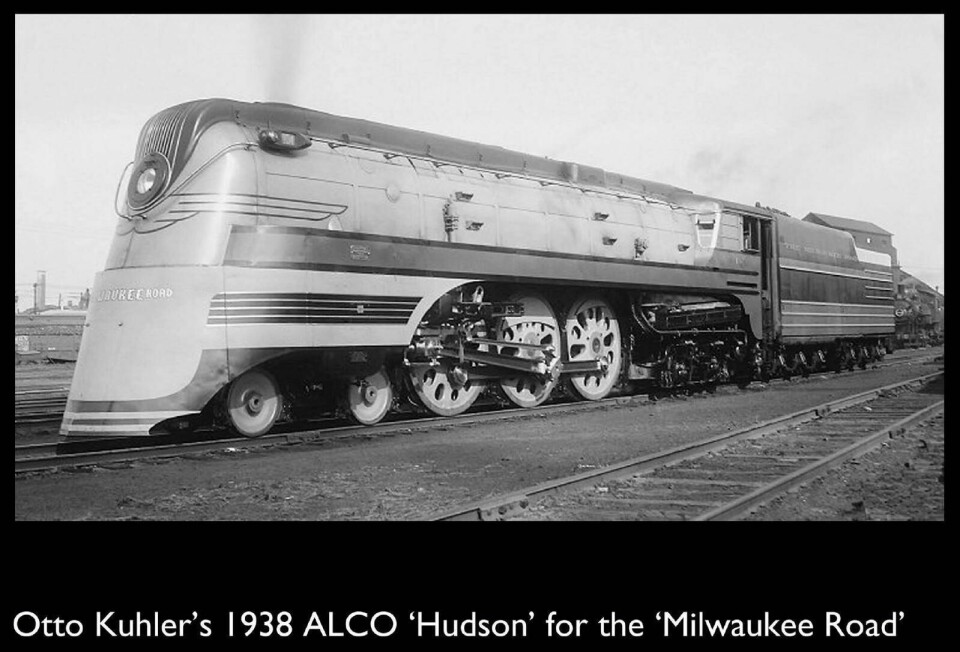

Four designers in particular became very well known at the time; there was nothing more impressive for a design group than to be involved in such a high profile project as a transcontinental train. Raymond Loewy and Henry Dreyfus are the two best known names; each headed a talented design team working under their direction. Less well known now are Otto Kuhler and Paul Phillippe Cret; Kuhler in particular was a highly talented designer whose work on streamlined trains was influential around the World. His design work for the ‘Milwaukee Road’, the Chicago – Saint Paul – Pacific route included the 1939 ‘Hiawatha’ train that included a spectacular glazed observation car.

Out of the 120,000 or so steam locomotives built and run in the United States, only about 220 were streamlined, or, as the Chicago & North Western called it, ‘steamlined’. Railroads went to the trouble to streamline steam locomotives for three reasons. First, some railroads, such as the Burlington, wanted steam locomotives as a back up in case the diesels that were powering most of their streamliners broke down. This was early in the development of diesel locomotives and reliability was still a problem.

Second, many railroads, such as the Milwaukee Road, didn’t believe diesels were powerful enough to reliably pull a full-sized train, and travel demand on their routes required much bigger trains than the little three- and four-car streamliners pioneered by Union Pacific and Burlington. In fact in 1937 the ‘Santa Fe’ proved diesels could pull a full-sized train, but some railroads stuck with tried-and-true steam technology for as much as a decade after that.

Third, some railroads decided it would be far less expensive to put a modern body onto an old steam locomotive, making it look fast and new, rather than buy new, expensive, and uncertain diesels. Even the Union Pacific operated supposedly modern streamlined trains with twenty year old shrouded steam locomotives.

Born in 1894, Otto Kuhler came to America in 1923 from Germany where he had designed car bodies for Snutsel Père & Fils in Brussels and most notably a very sporting body for an 82/200hp Benz. In 1928, after a period as an illustrator, Kuhler opened a design studio in Manhattan, New York, but it was not until 1931 he received his first railroad design assignment.

This was for the J.G.Brill Company, at the same time Kuhler was retained by the American Locomotive Company (ALCO) to work both with their advertising department and as a design consultant. His earliest streamlined locomotive designs were criticized as looking like inverted bathtubs but his well-designed liveries went some way to enhancing the look. Kuhler was even responsible for the design of the train’s interior including the napkins in the dining cars and all the curtains and fabrics.

He accepted that streamlining was more for advertising than improved speed and efficiency, but as he noted in a speech given in 1935, “Despite major technological improvements (such as superheating and roller bearings), ‘the man on the street’ couldn’t distinguish a 1915 locomotive from a 1935 locomotive. Putting a shroud on one made it special, as most railroads would discover when they put shrouds on 1915 locomotives”.

The difference with Kuhler’s locomotives was that they were designed from the start as streamlined machines. In his retirement Otto Kuhler returned to his first passion, drawing and illustration, he was a more modest and less flamboyant designer than his contemporaries but was undoubtedly one of the most influential in the field of railroad design.

Henry Dreyfuss could well be called ‘The father of Industrial design’, he was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1904, and first studied as an apprentice to designer Norman Bel Geddes. He opened his own design office in 1929.

Whilst Dreyfuss could be considered one of the celebrity industrial designers of the 1930s and 1940s, he was responsible for improving the look, feel, and usability of dozens of consumer products. Design critics have suggested that as opposed to Raymond Loewy and other contemporaries, Dreyfuss was not a stylist; he was a designer who applied common sense and a scientific approach to design problems. He also developed the concept of ergonomics coupled with anthropometrics and human factors (recently rediscovered as ‘HMI’), his book ‘The measure of man’ is still available and can be considered as a basic design tool for designers.

Dreyfuss and his studio were in great demand with the growing stylistic competition between the railway companies and some of the greatest looking locomotives came from his team; as did so many well known products, from John Deere tractors to Bell telephones, steam irons, vacuum cleaners and one of his final products launched shortly before his death in 1972, the Polaroid ‘Land Camera’.

There were a number of other designers engaged in the ‘Battle of Modernity’ in the 1930s and 40’s; most famously Raymond Loewy, but they also included the first woman railroad locomotive designer – more next week!