Comment: Too much minimalism?

Everyone is a minimalist these days, but beyond being a handy catch-all for pared back aesthetics, what does the term mean for car design? Are designers sacrificing ornament at the altar of functionality?

Minimalism is everywhere. But how can you tell? After all, this is a design language that, rather like Miles Davis’ calculated omissions, makes virtue of what you don’t see: pared-back interiors, lines so clean they are barely distinguishable, and touchscreens. Lots of touchscreens. The term has become a handy catchall for designers to frame design as a reductive process and is deployed in all manner of communications – from press releases to promo videos. Ubiquity diminishes meaning, so how should we interpret a term that is so frequently used, and passed over without a moment’s thought.

The seeds for minimalism were sown in another ‘ism – modernism. Stripping back the ornament, which obfuscated a greater truth, was seen as the path to a utopia. In the post-war era, modernism found its consumerist form in product design via the Ulm School – a reincarnation of the Bauhaus – and was expressed by Dieter Rams and his work for Braun. Form must follow function. Minimalism, which had far less to say than its angrier elder brother, became the acceptable face of modernism, which had drifted and become a byword for the failed dreams of the future.

Minimalism irked the post-modernists who saw it as a neutered version of modernism – a revenant shorn of political meaning and, even less forgivable, lacking in colour and decoration. You only have to look at the irrepressible vogue for the muted hues and precise symmetries of Scandi-style interiors to see who won that particular battle. For now, anyway.

In automotive design, minimalism has occasionally been misinterpreted as the act of simply removing various elements to reveal the structure of the car. Function over form. The result is labelling everything from a Caterham 7 to a Mini Moke as minimalism. The Moke is many things, but minimal it is not. A truer expression, in terms of exterior architecture, would be the Lucid Air by California newbies Lucid Motors, which, in its quietly curved silhouette offers little to intuit in terms of function. Car design as iconography. The obvious pitfall is a vehicle that lacks a distinguishing character – the sort of personality quirk that delights or infuriates, depending on your disposition.

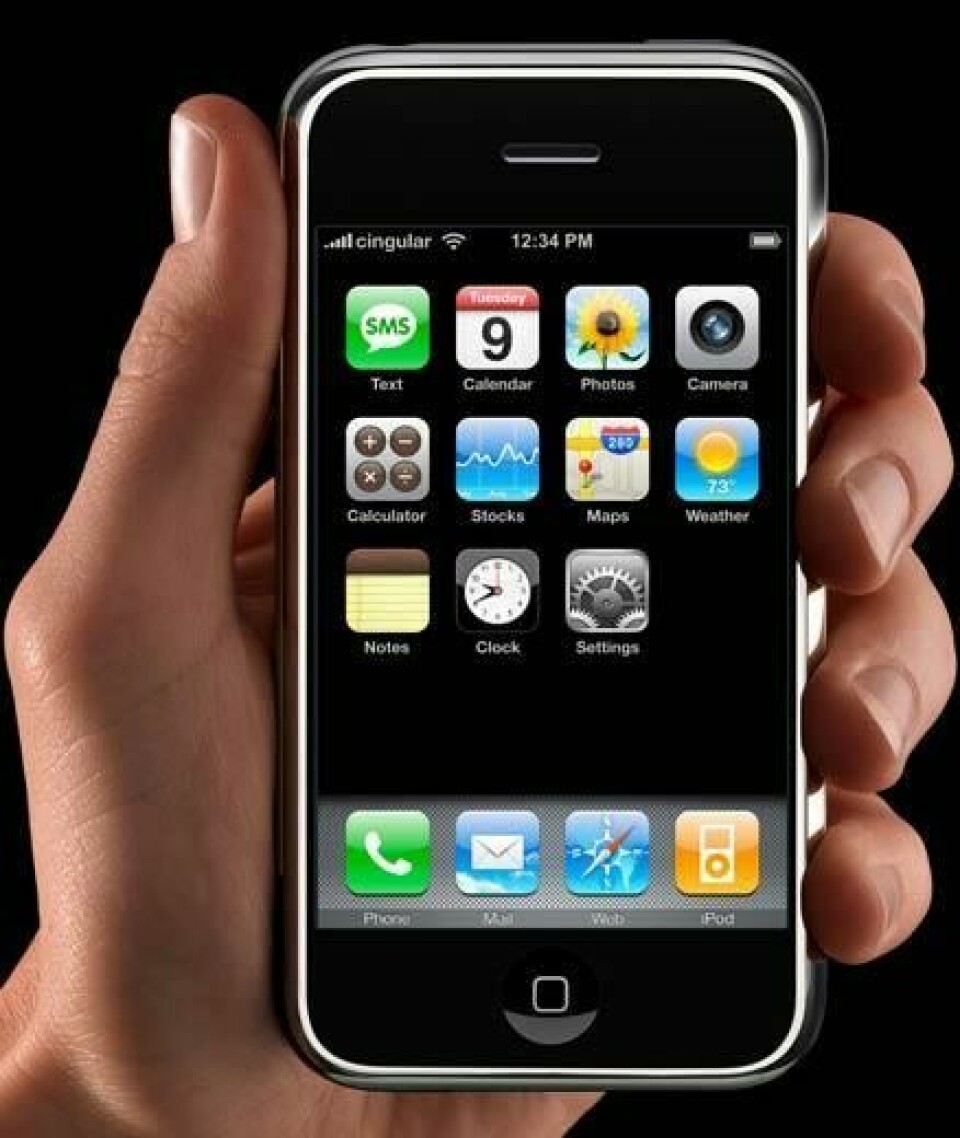

When it comes to minimalism, car interiors often owe more to Apple’s design talisman Jony Ive – the designer behind the iphone – than Ikea. Through his work with Apple, Ive waged a phenomenally successful campaign against buttons. I confess, I liked buttons. Before I surrendered to Steve Jobs’ worldview I had a Blackberry, which enacted my demands with a reassuring click. It was the lethargy with which the device met my requests for web surfing that curtailed our relationship. Otherwise, I’d probably still have it. Nevertheless, it is these small moments that establish an emotional bond between us and our objects. Architects obsess over door handles – materials, form, action – because they are one of few tactile elements of a building. A touchscreen offers none of this.

Car designers have an advantage in that there are multiple opportunities to forge an understanding between the driver and the object: the dampers on the indicator stalk, the shape of the gearstick or even the steering wheel. However, they must guard against getting caught up in minimalist zeitgeist, or at least the interpretation of it that places digital over analogue. The instinct for the functionality to remain hidden until needed, much like Rams’ fictional English butler, is understood, but conceal too much behind an impassive black mirror and those special moments that cement our relationships with cars can fall by the wayside. When viewed though the prism functionality reveals a paradox: the beauty of a dial for the windscreen demister is that it is always in the same place, not tucked away on a sub-menu somewhere.

Minimalism was a consistent theme throughout CDN’s recent virtual event, Car Design Dialogues. Design teams from Cadillac and FCA behind the brand new Lyriq and the newly resurrected Grand Wagoneer concept wrestled with the integration of technology into their respective vehicles. To their credit, neither team disguised all functionality behind a screen, deciding instead to pour their attention into a few well-executed details. “There is an artistry in the combination of clean lines and ornament,” said FCA’s head of interior design Chris Benjamin. “We know that as technology becomes a bigger part of interior design, that is how people are used to interfacing. We wanted to make sure it didn’t lose its soul. You can easily make something feel very cold if you just have a bunch of screens and nothing else.”

In practice, that meant a carefully crafted almost jewel-like rotary dial, and a sensitive transition between the primary materials – aluminium and wood. Cadillac, too, indulged in some rich detailing and textures – setting the interior pallet against a deep juniper blue. Like the team at FCA, the materials in the Lyriq judiciously applied while the interface between screen and human comes via crystalline rotary dial. Were these details strictly necessary from a functional perspective? Maybe not, but the design teams believed enough in tactility to include them. The counter argument runs that delight is today less about materials and detailing and centred around an incredible user experience – responsive screens that offer myriad uses, flawless connectivity, and allow us to personalise our environment, rather than subscribe to a designer’s prescriptive vision. Too often, however, countless layers of menus torpedo the minimalist dreams.

Perhaps the parameters have shifted. Our relationship with cars is changing – much like smartphones, we treat them as something to upgrade every three years or so. Couple this with a generation versed only in screens that will soon enter the market. Do they share the same passion for tactility and materials? Much less in investing in a long-term relationship with a car? Hard to say. But to continually fall back on minimalism, at least in its current expression, would be a mistake.