Geneva 2019: Citroën Ami One explores industrial processes, urban mobility

Jean-Arthur Madelaine-Advenier, Citroën’s head of interior design, talks details

“It’s not just a car, it’s thinking about urban mobility,” says Jean-Arthur Madelaine-Advenier, head of interior design, Citroën. “It’s something that people with no car culture, no driving licence could be attracted to. We looked much more at product design, connected objects, not just car design.”

A lightweight 425kg microcar which could be driven by teenagers and people without a full licence in countries including France, the Ami One has also been designed from the outset with sharing in mind, accessed on-demand via dedicated counters or pick-up points around a city – and with an accompanying range of services and fashion accessories.

“We built the story, and then that’s how we designed the interior,” Madelaine-Advenier explains. “We thought about urban young people, we thought about different scenarios of life, what they might want, and we thought about people we know: someone with kids, someone going shopping, going to the airport; what you have in your hand, where you would put a dog, and how you would leave the car, how you would change direction when you get in…”

?UMBRACO_MACRO macroAlias="RTEImage" image="547106" caption="" lightbox="1" position="left" size="large-image" ?

The end result, inside and out, is something very simple: in terms of interface, a single pod houses all the controls for the driving functions, and the user’s smartphone (docked onto a wireless induction-charging pad) is used for everything else, including locking and unlocking via a scanner above the blue rubberised door-pulls.

The projected head-up display mirrors the user’s app, supplemented by voice commands and a steering wheel-mounted scroll-menu. A bag (or a small dog) stows into the cubby in front of the fixed-position passenger seat, and a cylinder to the right of the ‘drive pod’ contains gearshift selector, a Bluetooth speaker, start button and hazard-warning button.

?UMBRACO_MACRO macroAlias="RTEImage" image="546995" caption="" lightbox="1" position="left" size="large-image" ?

“The smartphone was really supposed to be the centre of the experience,” says Madelaine-Advenier. One of the main things is that instead of having a combi cluster, it is inside your phone.” This aids the simplicity – “we wanted to have something that was extremely intuitive, so first thing, when you get into a car, in a few seconds you need to understand what is there, the main functions, how you get it and how easy it is to drive” – and also helps guard against technological obsolescence, he adds.

Eye-like graphics for the personal digital assistant add a human touch, as does the handwriting-style font used for the GUI: “We really try to make a language between colour and trim, UX/UI and interior design, which is all the same language, and every time we do new things with colour and trim, we try to bring that into the graphic design of the screen.”

?UMBRACO_MACRO macroAlias="RTEImage" image="547107" caption="" lightbox="1" position="left" size="large-image" ?

In such a small vehicle (2.5m x 1.5m) the sense of space is maximised by the light interior, white with bold splashes of bright blue. The white is enabled by dirt-resistant surface treatments as used in aeroplanes; and the seat and flooring materials are created by Dutch materials design start-up Studio Plott, using-3D printed plastics sprayed with powder for a soft-touch effect.

Such techniques are ideal for personalisation and for making materials for individual or case-specific applications. “It can look like velvet or suede,” says Madelaine-Advenier. “It’s a way to produce this seat: you don’t need to produce a big number to make it profitable, and if you want to change the graphic tomorrow, you can change it.” The graphics of the cut-out seat-backs were inspired by the covers on traditional Parisian café chairs, he adds.

?UMBRACO_MACRO macroAlias="RTEImage" image="547099" caption="" lightbox="1" position="left" size="large-image" ?

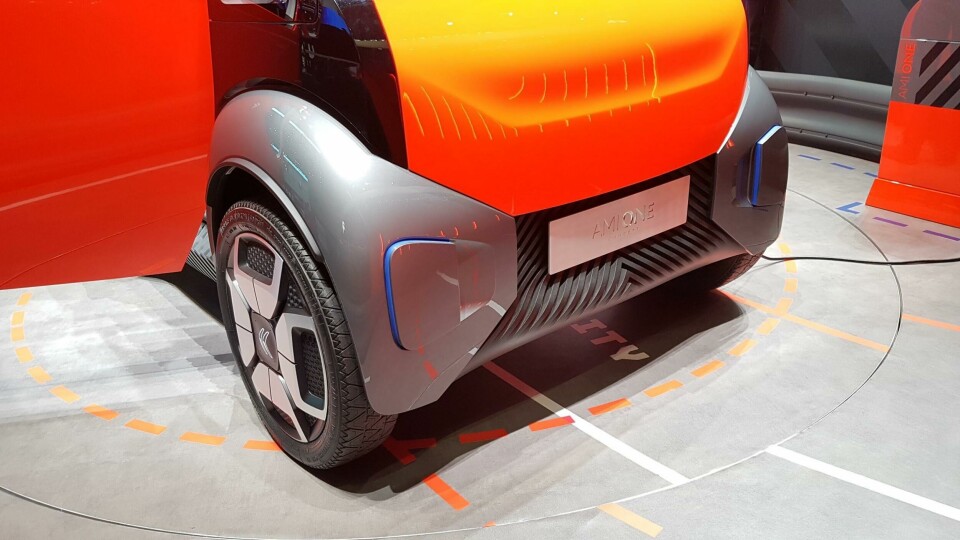

The most pertinent points about the Ami One’s design are arguably those not instantly visible, however: it has not just been designed to show a proposal for urban mobility, but to explore ways of reducing production costs. The asymmetrically-opening sliding doors enable exactly the same door to be used on either side; the Airbump-clad front and rear ends have identical components, albeit fitted opposite ways-up; bumpers, wings and rocker panels are identical; the DRLs and rear lights are reversible for each side; and the four-part door mirrors and door handles simply reverse as well.

?UMBRACO_MACRO macroAlias="RTEImage" image="547100" caption="" lightbox="1" position="left" size="large-image" ?

A canvas roof (slid open using another blue strap) and polycarbonate translucent panels save weight, and much of the visual impact is created by the two-tier lighting and application of colour, rather than surfacing or sculpting, with added grooved graphic details on the bumpers and rocker panels referencing the Citroen chevrons.

?UMBRACO_MACRO macroAlias="RTEImage" image="546993" caption="" lightbox="1" position="left" size="large-image" ?

“The idea was to get as minimal a number of pieces as possible,” says Madelaine-Advenier. “Usually in the car industry, we do everything symmetrical, and we thought instead of doing that, we’re just going to make the same piece. If you keep the same hinges, one door is going to open one way and the other one the other way around. If you want to reduce the cost to build a car, an electric car, you want to reduce the cost of everything on top of the battery: we can’t squeeze the price of the battery, so have to find a clever way to reduce the cost [elsewhere], use less space in the factory to make fewer pieces, to optimise the industrial process.”

?UMBRACO_MACRO macroAlias="RTEImage" image="547108" caption="" lightbox="1" position="left" size="large-image" ?

In turn, this has in itself defined the final appearance and character of the vehicle. “If you think from the production and the way you’re going to build it, it creates its own aesthetic – the shape is inspired by these constraints,” Madelaine-Advenier concludes. “That fits also our research at the beginning: we wanted to avoid something that looks too much like it was designed as a car.”