Why have cars become so aggressive?

It’s long been known that attributing human characteristics to cars can make them more appealing. But are cars becoming too aggressive?

It’s long been known that anthropomorphism – the attribution of human characteristics to non-living objects; in this case cars – has the ability to greatly enhance emotional appeal.

Successfully combined, the front end, grille, fascia and headlights have the capacity to form a distinctive face, a term now so ubiquitous in car design that most studios refer to the ‘face’ of the car when talking about front-end character and distinctive down-the-road-graphic identity.

As with human faces, car faces can be very effective in communicating personality, emotion and character. And with many owners regarding car ownership as a means of self-expression, the ‘face’ of the car is fundamental in vehicle choice.

We’ve seen ‘happy’ cars, such as the Austin Healey Sprite, ‘sad’ cars like the Ford Anglia, and ‘surprised’ cars including the Morgan Aero 8. In modern times however, it seems that one particular type is becoming increasingly prevalent; the ‘angry’ car.

The face of the angry car typically features angular, recessed headlamps – evocative of narrowed eyes and a furrowed brow, a gaping grille with vertical slats – which forms a snarling mouth complete with bared teeth, and aggressive sculpting of the bonnet – recalling popping veins in the forehead. This is often topped off with a sharply protruding front splitter, akin to a jutting jawline.

By contrast, the happy car presents a very different visage, large circular headlamps, intakes with upturned lower corners and soft, rounded forms creating an impression of happiness, even innocence and joy.

Today there are examples of aggressive design across every genre of vehicle, take the Toyota Aygo, where the first generation had the appearance of a cutesy anime character, the cars’ DRG now exhibits a super-aggressive ‘X’ graphic. The once joyfully innocent MX-5 has evolved into something resembling a predatory lizard, and Ferraris’ F12 has the malevolent grin of a killer clown. Even the face of the traditionally neutral, inoffensive Golf now has sinister overtones – particularly apparent in R form. Furthermore, some manufacturers are even basing their entire form language around angry design. Kia has its ‘tiger nose’, while the previously conservative Lexus has an entire range of vehicles seemingly styled by machete. Audi’s once benign expression has become a grumpy frown of late, exemplified by the latest Q8 concept. Even Volvo now has ‘Thor’s Hammer’ headlights.

Perhaps car designers are merely responding to public demand, after all, there has been research conducted signalling a preference for the angry cars amongst the public (http://www.telegraph.co.uk/motoring/3158161/Cars-with-angry-faces-are-more- appealing.html). Why is this? What makes the angry car so appealing? and what effect does this have on our driving environment?

One explanation might be that larger, more ‘high status’ vehicles have traditionally had a more ‘serious’ and ‘brooding’ expression; BMWs’ ‘shark nose’ for instance. In a market obsessed with ‘premium’, perhaps aggressive design is seen as a way to add much valued cachet to a vehicle or brand. However, the premium vehicles of yesterday were generally much more subtle than todays’ caricatures. Timeless restraint used to be more highly prized in luxury cars; Bruno Saccos’ masterpieces for Mercedes in the 1980’s is possibly the best example. Exotic cars were more often about elegance and beauty, rather than aggression, the Jaguar E-Type and Lamborghini Miura were most certainly not examples of angry design, their expressions were serene and graceful, rather than vicious.

Perhaps then, angry design is more of a reaction to the overcrowded and congested roads of today, together with a culture of impatience. Nobody enjoys traffic congestion, and consciously or subconsciously, many drivers may want to bellow obscenities at those impeding their progress. Perhaps for some, the angry-faced vehicle is symbolic of their pent-up frustration, and represents a way to project this to other road users. After all, even the most icy-cool and rational of drivers may start to feel slightly uneasy with the gaping maw of a BMW X5M advancing in their rear view mirror. The knock-on effect is that this anger breeds more anger and anxiety, when faced with a commute full of snarling predators, a Volkswagen Beetle no longer seems appropriate. In an increasingly hostile roadscape, many more drivers wish to feel protected by their cars, and perhaps psychologically, an angry car seems more up to the job. Maybe some of todays’ fierce vehicles can be likened to medieval gargoyles, intentionally ugly and intimidating devices, intended to ward off the evil intentions of others.

All of which is deeply unfortunate, since an increase in aggression and anxiety on the roads is hardly conducive to safety, let alone the stress levels and general well-being of motorists. Driving should be one of the simple daily pleasures many of us experience, rather than an anxious battleground. It could be said that the happy-faced cars of old were symbolic of a time when roads were less congested and driving felt like an adventure, rather than a chore.

Another consideration is that our wider cultural environment has simply become more aggressive and cut-throat. Many younger drivers (and designers) have grown up in a world where on-screen violence, shoot-em-up video games and gangsta rap are the norm, so it follows that many also desire aggressive looking cars. Anger and aggression have so often been presented as ‘cool’ and aspirational, friendliness and innocence far less so. Car-makers frequently express their desire to appeal to a younger audience and perhaps an added dose of aggression is one way to add ‘youth appeal’. Jaguar certainly seems to think so, eager to shed its’ ‘old man’ image, the company has played on the sinister connotations of its’ products in recent marketing, such as its’ ‘villains’ advertising campaign (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e7gR7EYjcP8). With this in mind, it can’t be a coincidence that the XE and F-Pace models exhibit ever larger and more gaping air intakes, coupled with ‘angry eye’ headlamps, in stark contrast to the softer forms of many older models.

Exceptions to the angry trend have become few and far between. They are mostly found amongst smaller cars, the most obvious being the Fiat 500 whose joyful appearance forms a key part of its identity. Other retro designs such as the Mini Hatch and Volkswagen Beetle take a similar path. Additionally, Renault’s current Twingo echoes the cheerful demeanour of the 1992 original, and Volkswagen’s Up! is a great example of how to execute happy design without descending into cutesiness. The Up!’s large ‘eyes’, prominent circular emblem and upturned lower intake create a cheeky, yet tasteful expression. Though sadly, the latest model’s recent facelift has diluted this.

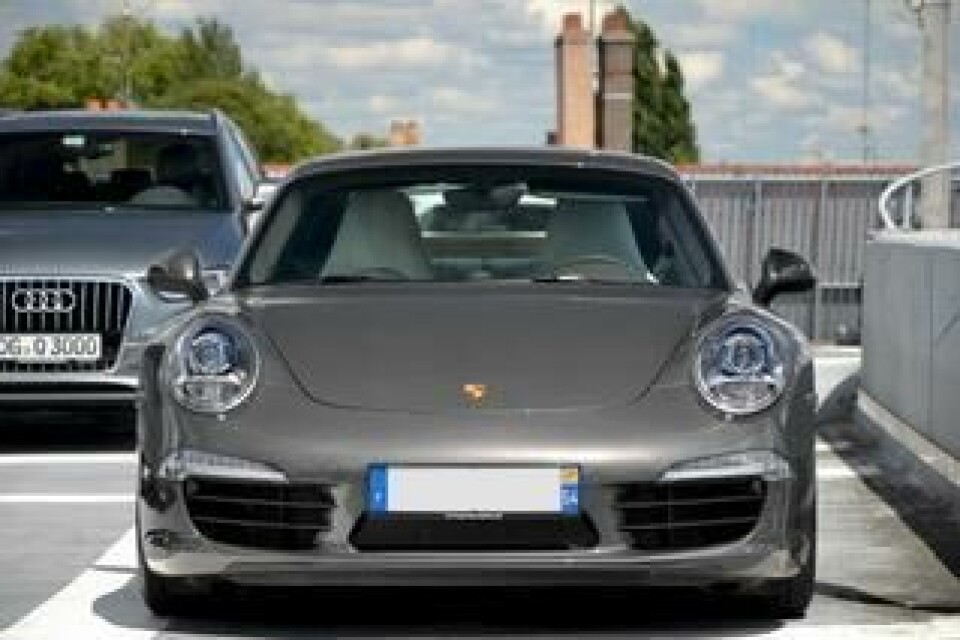

Amongst larger, some might say ‘more aspirational’ cars, the continued success of the Porsche 911 illustrates that not all cars need be sullen and aggressive, even those of a sporting nature. The 911’s happy face has become iconic – the car manages to be at once friendly, endearingly awkward and unconventionally beautiful. It’s power and dynamism is expressed by sensuous curves and a poised stance, rather than by an angry scowl on its face. The 911 theme continues throughout other models including the Boxster, Cayman and Panamera, lending them a similar upbeat aura.

Of course, variety is the spice of life – and car design – and a market dominated by sickly-sweet or sentimental design would be no more desirable than the current obsession with animosity. Nonetheless, while it’s no bad thing for a thrusting sports saloon (sedan) to be subtly menacing in appearance – Lamborghinis wouldn’t be the same without their outlandishly aggressive styling – it does seem as if there are a few too many gargoyles on today’s roads.