Design Essay: Punctuating the Logic of Equilibrium

What is it that makes some products highly successful even though they are different to anything the public has seen before? And is different always better? Let us look at two examples, BMW and Motorola, to understand the answers

What is it that makes some products highly successful even though they are different to anything the public has seen before? And is different always better? Let us look at two examples, BMW and Motorola, to understand the answers.

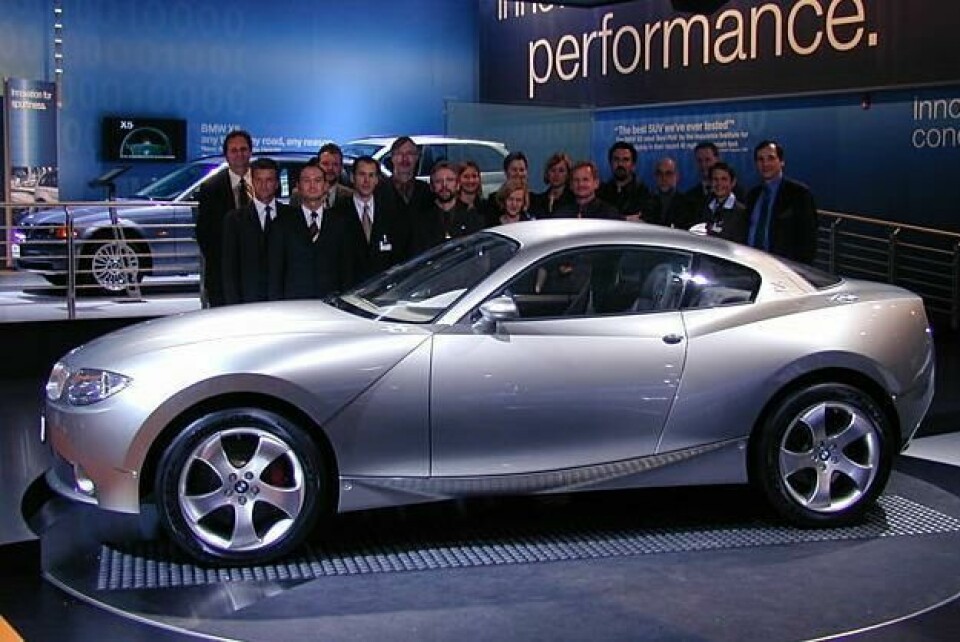

BMW has done a lot of things different with the aesthetics of its current generation of cars, starting with the 7-Series launched in 2002. Design chief Chris Bangle has used the phrase ‘punctuated equilibrium’ to describe the jump forward BMW has tried to achieve with its current design language.

The phrase originates in a theory of biological evolution in which long periods of slow or no change are interrupted by large leaps as new species appear or existing ones alter significantly in response to environmental changes.

Today BMW is certainly an exemplar of this idea. The current models created a sharp break from the aesthetics of the previous generation by introducing swaths of angularity (‘flame surfacing’) and emphatic details like the elaborately shaped headlight lenses.

The initial heated controversy over the styling has abated in the last few years, perhaps because the expressiveness has been toned down in successive models and some of the BMW cues have been picked up by others. The hotly-debated ‘bustle’ tail has shown up in more subtle variations on the Acura RL, Hyundai Azera, and even the new Mercedes S-Class. But people have also simply become more used to the forms.

Kurt Anderson calls this process ‘sensibility osmosis’. In his novel Turn of the Century, the main character, George Mactier, suddenly has a realization about some buildings he’d always considered ugly:

“Then he realizes: the skyscrapers that looked atrocious in 1980 and 1990 now, in 2000, look quaint, elegant, swingy. He isn’t aware of having revised his opinion; his opinion has been changed for him, updated automatically, gradually, by sensibility osmosis, leeching from glossy magazines and newspaper style sections into George’s brain…. As of this morning, these buildings, which George has spent a few seconds every week of his adulthood loathing actively, are looking kind of cool.”

Looking beyond cars, the Motorola Razr is an example of a highly acclaimed product that has led to a new formal language and use of materials in mobile phone design.

What is remarkable about the Razr is that very few people dislike it, yet it looks unlike any phone that has come before. A testament to its popularity – and how difficult it can be to predict market acceptance – is this statement from the former CFO of Motorola, Geoffrey Frost, who shepherded the project through the company and sadly died soon after the phone’s launch:

“Our traditional research told us there was a total available world market of about two million units for a $499 phone. We sold over two million units in the UK alone.”

The Razr is remarkable for how well it balances the conflicting forces of rational familiarity and imaginative newness. The design is very logical in that it is a clear derivation of what has come before, and is obviously beneficial: it is extremely thin, which makes it easy to carry around and attractive to look at. From a brand perspective it is a logical connection back to Motorola’s groundbreaking StarTAC phone of a decade earlier.

While the logic underpinning the design is familiar, the design solution is unexpected: it is much wider than normal phones, and has a shrink-wrapped form that is neither smooth nor ‘ergonomic’ as people are used to. Instead of the usual plastic it is encased in metal, which gives it both a distinctive look (especially the keypad) and an unusually cool, durable feel.

The Razr is a contradiction: a logical progression on one hand, yet an unexpected break on the other. It succeeds because its logic is informed by multiple perspective (customers and their needs, brand legacy, technology and manufacturing capabilities), and is unexpectedly different in a way that does not violate the logic.

In fact, it is the unexpected approach which allows a dramatic jump in the phone’s ability to address the needs of the logic - it was so much thinner than anything else on the market at the time than could have been achieved through ‘normal’ evolution. So the slowly changing equilibrium is punctuated.

The logic driving BMW’s aesthetic shift was two-fold: the Chinese market was becoming increasingly important and BMW’s styling was considered too bland in the luxury tier, and the dramatic changes in underlying electronic and performance technologies were not being reflected on the exterior.

Making these logical yet unexpected breakthroughs is not easy. Logic can set up its own momentum that to company and customers alike can seem timeless and progressing in small steps, in other words, the equilibrium. That is, until someone breaks it with an unexpected product.

It’s this momentum of perception which surfaces prominently in focus groups and other ‘traditional’ research methods Frost talked about, and is often taken at face value. It can be difficult to resist, and often limits the ability to come out with much-needed breakthrough designs that open new markets, especially to a brand that is well-defined in the public’s mind. Jaguar, for example, has been unable so far to make the break from the momentum created by Sir William Lyons all those decades ago.

To both their credits, BMW and Motorola were pro-active at being the instigators of the unexpected. Both were fortunate that top-level executives supported the need for finding the unexpected, but each was also clear on the logic behind the decisions. Newness without logic is just novelty, and that is not sufficient, just as random mutations that provide no competitive advantage are discarded in nature. To ensure long-term survival of a brand/species, unexpected developments must be relevant to the logic of their environment. Only through this will they create ongoing competitive edge.