GM design bosses outline importance of sketching

Senior design leaders at General Motors give their take on the role of sketching in modern studios

It’s no secret that putting pen to paper is the foundation of car design. Communicating ideas, experimenting with shapes and refining details can all be done quickly, easily (relatively speaking) and in one’s own distinct style. And as CDN readers will know, the artwork that is created by a designer does not go to waste once the car hits the road. It is often central to marketing efforts and telling the story of why that car exists and how it came about.

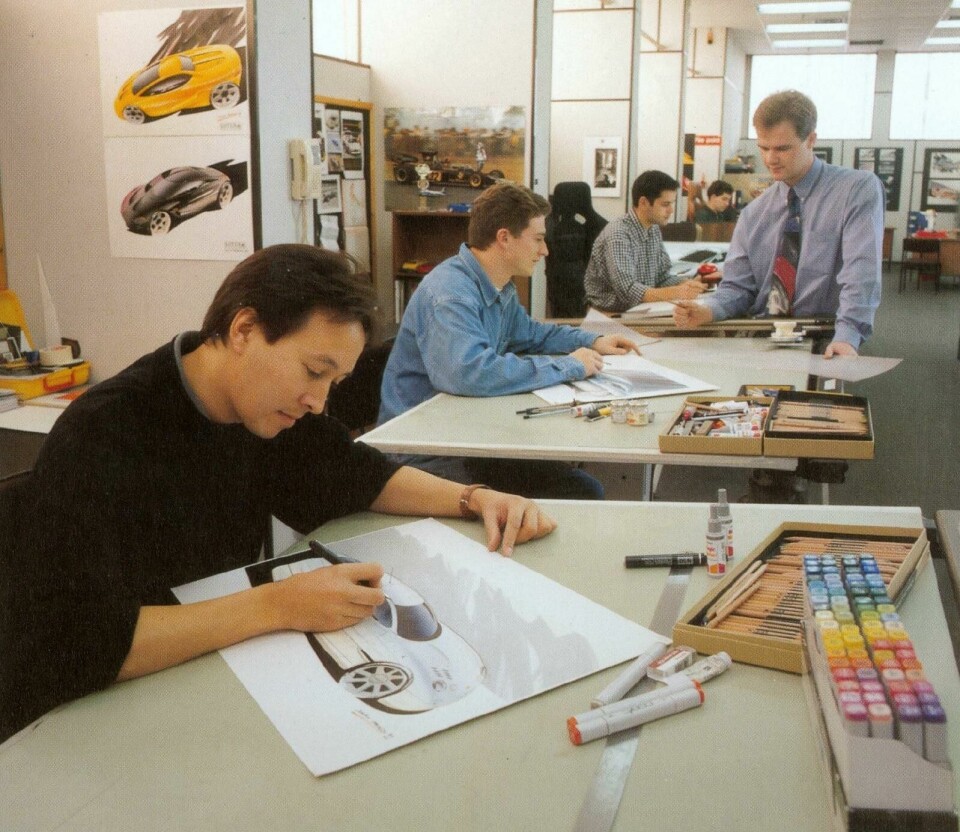

On a visit to General Motors’ European design outpost, we grabbed some time with top design bosses to get their perspective on the skill, what it means in an age of digital tools and whether it is still seen as the barometer for whether someone can walk the walk in car design.

“I think about this all the time,” muses Sharon Gauci, Buick’s global design director. “The new tools are brilliant, but they have a particular moment in the process. I’ve been encouraging my team to get back to basics, not only to get more ideas out but also to better understand the design in the first place.”

To hammer home the point, Gauci says she often looks for the most basic sketch at the start of a project, not necessarily the “shinest finished sketch.” It helps the team to crystalise exactly what the direction will be before heading to more time-consuming and investment-heavy processes.

“We’re doing some early work right now where the designers have had a few weeks of iterations and felt they were ready to go to scale. But I said, no, you need to go back and we need to spend another week understanding the design more through sketches, and not trying to find the design in the clay.”

Julian Thomson, brought in to lead the GM Advanced Design Europe studio, suggests that a simple sketch – ideally repeated on the spot – can illustrate the true skill of a designer; other tools could potentially mask their shortcomings. Indeed, it’s difficult to fake a sketch and although not a formal element of the hiring process, Thomson does see plenty of value in seeing what a designer can do on the spot.

“If I look at a portfolio and see somebody can draw a cool sketch of a car on a post-it note, they’ve got my interest,” he says. “If they can do another car on the same bit of paper which is just as good, they probably have the job because it shows that the first car wasn’t a fluke.”

To be clear, not every sketch needs to be award-winning. “Out of 80, if they’ve done two really good cars, it shows that they really know what they’re doing.”

Global VP of design Michael Simcoe, set to retire this summer after a stellar career, highlighted the difference between doodling and sketching with intent. The point being that designers should ideally be able to translate what they are doing into a feasible product. “It’s about sketching with an understanding of what you’re sketching,” says Simcoe. “The worst thing is someone who has styling technique and can do a wonderful sketch, but then you get them in the studio and they can’t interpret it, they can’t explain it, they can’t progress it into a three dimensional form.”

GM design leaders, he says, ensure that new designers have mentorship over their first couple of years after joining. It is an “intense” process he says but one that gives the up-and-comers a chance to “make their idea and see it in reality. If you can’t do that, you can’t have an effect [on the project].”

Ideally, a young designer will be paired with an experienced modeller who can help them see why a sketch – done in a certain way – makes it easier to understand how to work a clay or digital model as the next step.

“You sometimes see a square block of clay and young designers have a wonderful sketch, but they’re twiddling their thumbs because they don’t know how to move the volumes,” Simcoe explains. “It’s always nice to put a young designer with a more experienced sculptor. I learned the business that way.”

As for the specific tool in question, it shouldn’t really matter. In the past, Thomson recalls some designers scrutinising the kind of pencils and paper that others were using. Many may have had similar thoughts in other situations: that runner is only quick because they have special shoes; the golfer can only drive that far because of a fancy club. It can’t be down to pure talent, can it?

“A lot of designers used to think there are tricks to the trade,” he explains. “I remember hosting a live sketching session and people would say, ‘ooh, that’s a Prismacolor 79, navy blue. I need that.’ Or, ‘well we would sketch like that, but we can’t because we don’t have that paper.’ It’s an illusion that the tools are what’s needed.”

To that point, the definition of a sketch seems to have evolved slightly to include not just pen on paper but stylus on tablet. On visits to studios across the globe, the latter seems to be increasingly common. To the purists, it feels at odds with the traditional analogue process; to others, a natural convergence of hand skills and the latest equipment. Generally speaking, a tablet sketch might not be the best starting point – at least in the eyes of leadership.

“They’re not the traditional pen and paper,” Gauci says, “and in general I’d rather have multiple design proposals that are quick and scrappy than one rendered design that has taken an entire week. We can render when we’ve found the design.”

“Paper sketches are more of a commitment because going back and correcting is more difficult,” says Simcoe. “I’ve never sketched using a tablet.” Thomson shares a similar view and sums things up nicely. “When you take away all of those other tools, the designer is stripped bare and you can see that they know what ‘good’ looks like.”