The return of primitive shapes in exterior design

Primitive shapes – squares, circles, triangles – are making a comeback in exterior design, argues Aysar Ghassan who tracks their origins in modernism and contemporary applications

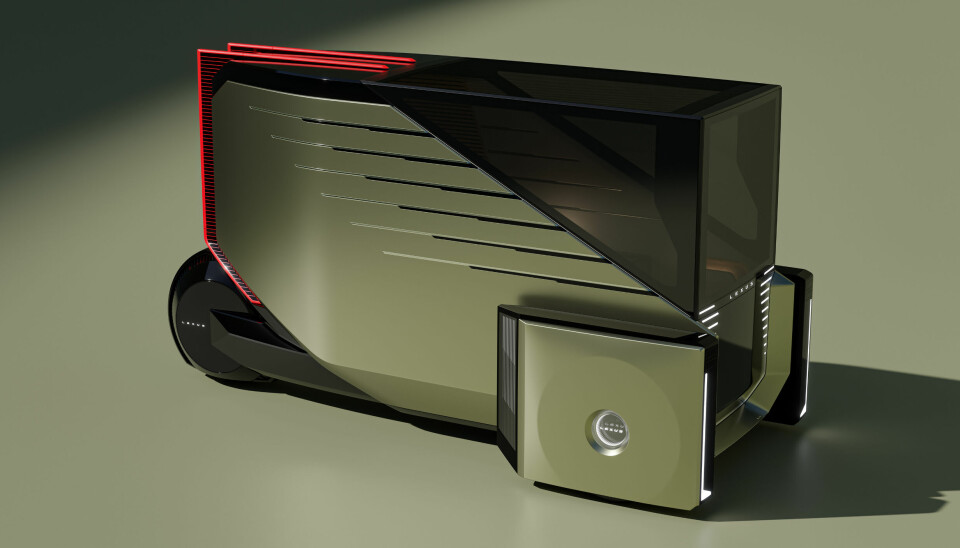

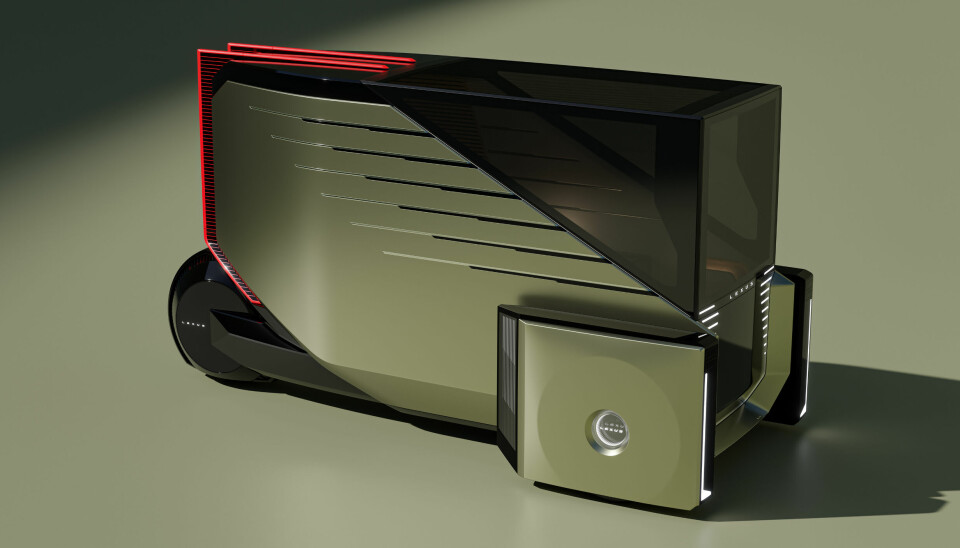

Simple shapes like squares, triangles and circles, hold a special place in industrial design. They’re bold, have served as a vehicle for advancing society, and can apparently transport us to a spiritual dimension. For over 100 years, designers have been turning to them when trying to upend the status quo, and in-so-doing have given us iconic pieces. Right now, the world of automotive exterior design is brimming with primitive forms. Take Slate Auto's functional box or Lexus' LS Micro concept. Why might this be? What are designers reacting to, and where might the mushrooming of elemental shapes take us?

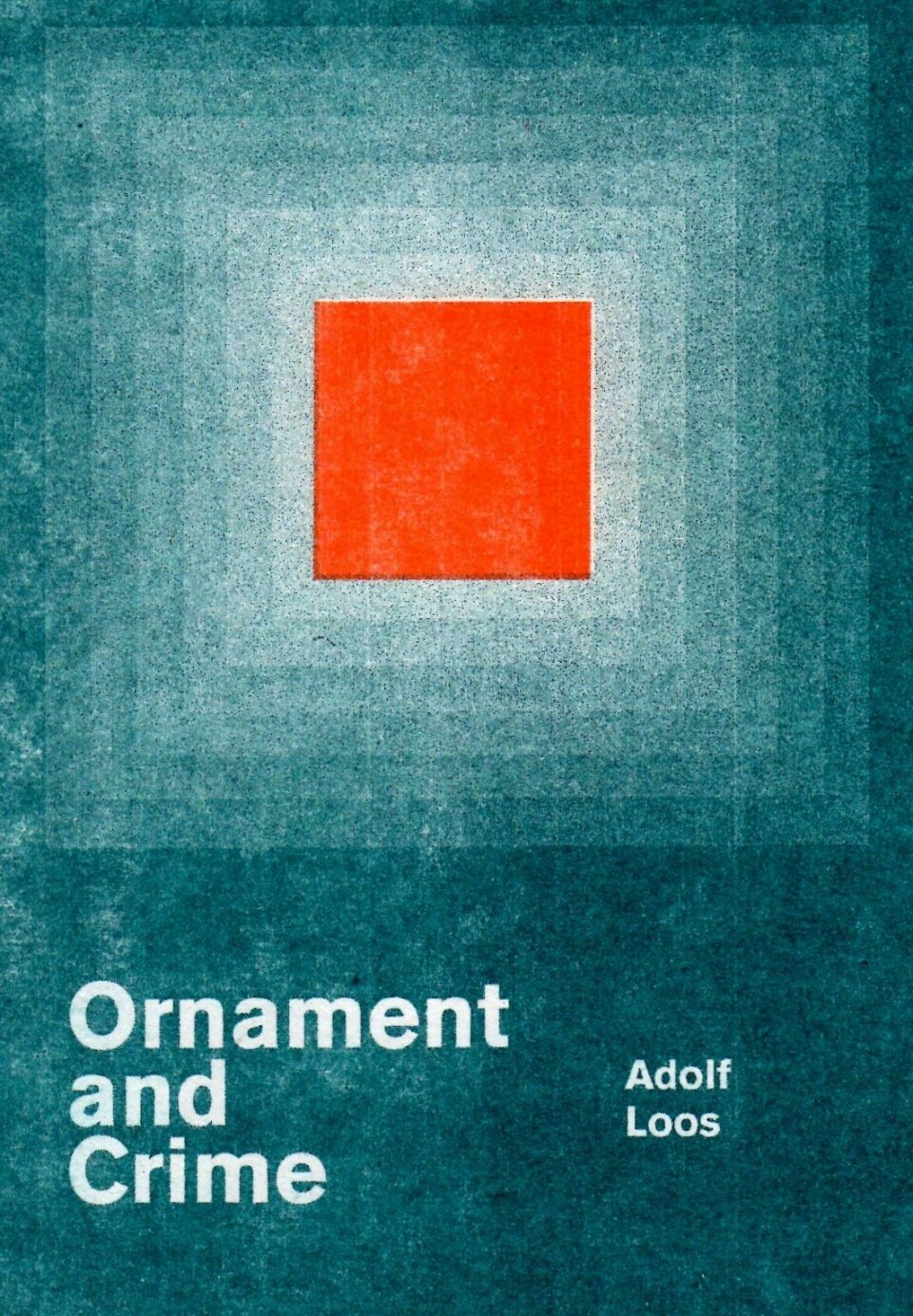

At the beginning of the 20th Century, buildings and other designed objects in Western countries were festooned with decorative motifs. A disparate collection of architects and designers became disgruntled with this situation, the most vocal being a young Austrian-Czechoslovak named Adolf Loos.

Loos dismissed patterns on artefacts as being wasteful; they served no function and were causing society to regress. His 1908 essay, ‘Crime and Ornament’, argues that for society to progress, designers and architects have instead to turn to timelessly simple, functional forms: “We have outgrown ornament, we have struggled through to a state without ornament. Behold, the time is at hand, fulfilment awaits us.”

Despite holding despicable views on a range of cultures and communities, Loos’ design philosophy influenced a generation, spearheading the growth of ‘radical modernism’, a movement in design and architecture in which elemental shapes came to the fore. Totemic names of the era include the German architect Walter Gropius, founder of the Bauhaus School of Art and Design, and the Swiss-French impresario Le Corbusier. Taking Loos’ sermon on a bit of a tangent, Bauhaus tutor Wassily Kandinsky claimed that the simplest shapes, triangles, squares and circles, represent visceral human emotions. Kandinsky conceived his influential colour theory around these shapes, certain they provide a gateway to the spiritual world.

It’s all too easy to criticise the machinations of radical modernists, but there remains something about primal shapes that continues to fascinate. For example, it is likely that their presence and layout have helped to drive the ongoing admiration many have for the mid-century appliances created for Braun by Dieter Rams. Exterior styling did not escape the gaze of radical modernists.

In 1936, Le Corbusier sketched the ‘Voiture Minimum’, a vehicle conceived to supersede the decidedly more intricate Ford Model T as the car of choice for everyday folk. With its planar aesthetic and focus on basic forms, the runabout was meant to nestle seamlessly into the hyper-futuristic urban design system that Le Corbusier and his peers believed would enable a more progressive way of living.

Following the romanticism of the immediate post-war period, movements such as pop art aimed to deconstruct and reinterpret the cultural landscape, while the subsequent psychedelia of the 1960s gave designers further leeway to experiment. Primitive shapes began to resurface and were put to work in the name of testing aesthetic and functional boundaries. The 1968 Quasar Unipower City Car, a glass box on wheels, transformed occupants into rolling installations while the equally idiosyncratic and questionably named 1972 ‘Kar-A-Sutra’ was an early attempt at envisaging ridesharing. With its monovolume profile and multi-use philosophy, its designer, the maverick Italian architect Mario Bellini, claims to have invented the MPV.

It was left to a celebrated crop of Carrozzeria (Bertone, Pininfarina and Italdesign (Giugiaro was, incidentally, a huge fan of Le Corbusier’s Voiture Minimum and had a full-scale wooden model made in 1987)), to definitively realise the potential of primitive forms. Together, they initiated a revolution in car styling which saw elemental shapes come to the fore in the 1970s, influencing the trajectory of design for a generation. Kicking off the decade, Paolo Martin’s 1970 Ferrari 512 S Modulo wholly reimagines supercar manufacturing, usability, proportions and graphics. Though the side-view is probably its most famous aspect, the rear end of this Pininfarina creation remains a spectacular assemblage of elemental shapes.

Stark four-sided forms take centre stage on Giugiaro's 1972 Boomerang. Its wheels alone are a lesson in how to arrange rectangles. Gandini’s 1978 Lancia Sibilo, a favourite of mine, was designed to resemble cast steel. The Bertone concept features chiselled front and rear lights, chunky wheel arches combining rectangular and triangular surfaces, and a circular aperture in the side glazing which is straight out of Le Corbusier’s playbook. A year later, Gandini struck again, this time with the Volvo Tundra, which would, in the following decade, morph into the multi-million selling Citroen BX. With the success of the BX, simple forms, albeit in a slightly tempered configuration, had gone mainstream.

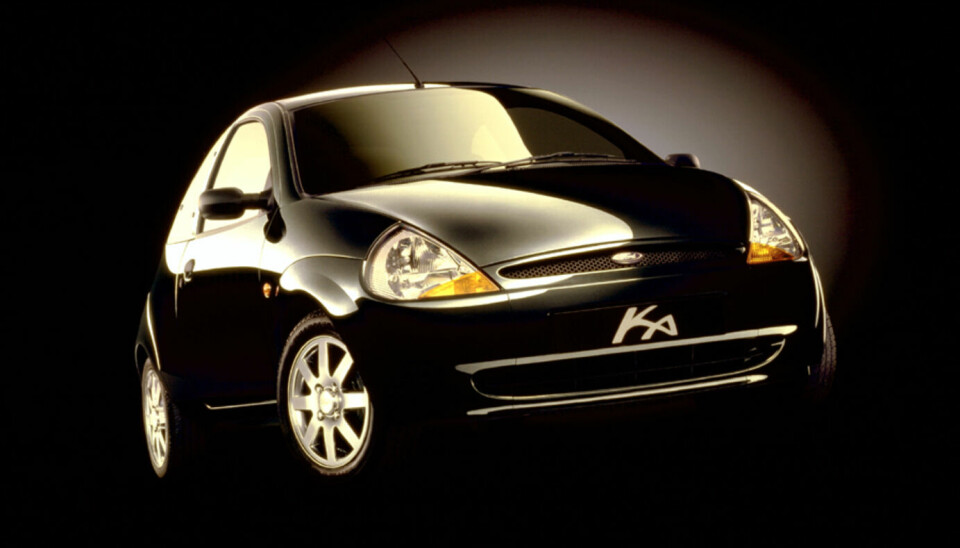

Over a decade later, as the start of the 21st Century loomed, Ford turned to elemental forms when kick-starting an in-house design revolution. Triangles, squares and rectangles contribute greatly to the 1995 GT90’s iconic character. The supercar signalled the dramatic arrival of Ford’s ‘New Edge’ aesthetic language and pre-empted the subsequent launch of classics like the Gen 1 Focus and Ka.

Elementals have once again infiltrated exterior styling. Oblongs help to construct the Hyundai Santa Fe’s wonderfully monolithic DRG, while squares and triangles embolden the wheels on Mobilze’s Duo/Bento. Circles take pride of place on the Peugeot Polygon’s wheels and the Honda Micro EV’s bonnet features a distinctive round nose. Rectangular panels on the diminutive Dacia Hipster’s side help to give it a certain pluckiness and the oblong front and rear masks on Jaguar’s Type 00 contribute to a design Rubicon delineating the concept from its forebears…The list goes on…All of a sudden, Le Corbusier’s automotive escapade feels strangely contemporary.

Several factors seem to be fuelling the rush to return to simple forms. Firstly, there’s the imperative to stand out in an ever more competitive ecosystem, and back-to-basic forms are anything but backwards in coming forwards. Then there’s the retro resurgence, which continues to be an important trend in car design. It’s evident that today’s deconstructed exteriors owe more than a little to the maverick creations of the 70s and 80s. But I think there’s more to it than this. Though today’s cultural climate is vastly different to that which drove Loos and co., there are some parallels with the contexts that fired up those radicals.

Over the last decade or so, parametric patterns have made their presence felt in exterior design, and as with any widespread movement, there was bound to be a backlash. We are certainly seeing that now and replacing decorative arrays with primitives represents a sure-fire way to wipe the slate clean. Then there’s the issue of function. Famously, modernist gurus of the early 20th Century stipulated that ‘form should follow function’.

Back then, primitives fulfilled a physical function — a square backrest on an armchair supported the occupant, large oblong windows on a building maximised access to daylight. Today, stripped back shapes on car exteriors possess a metaphorical function. Their pared back essence conveys a sense of purpose, narrating clarity of vision.

Linked to the idea of vision, is the issue of ‘the future’. Advancements in technology are bringing tomorrow ever nearer, but until recently, many cars weren’t looking especially revolutionary. Elon Musk, Tesla’s CEO, has repeatedly said that the Cybertruck looks like it does because ‘the future should look like the future’. Design chiefs across OEMs appear to have taken note and seem to be turning to primitives as a time-honoured way to generate a future aesthetic.

Lexus’ LS Micro, a luxurious single seater whose exterior hosts a suite of elemental forms, travels backwards in time from a cityscape which has yet to be realised. It wouldn’t look out of place parked outside Zurich’s Pavillion Le Corbusier.

The concerted influx of primitive shapes could unleash new possibilities for exterior proportions, contributing to the formation of a radical aesthetic, helping to definitively draw a line between gas powered cars and their EV successors. But more than this, it could lead to the adoption of new business models and the transformation of user experience. US-based Slate Auto are set to realise some of the potential of the revolution in manufacturing and modularity inherent in Martin’s Ferrari 512 S Modulo. The resurgence of elementals could nudge other OEMs into following suit.