‘In the race to be “cool”, quality and coherence are being left behind’

CES 2024 demonstrated that established OEMs like Volkswagen, BMW and Mercedes are still asking the wrong questions when it comes to user experience, writes Drew Smith

For a few years now, CES has been considered the most significant motor show on the international circuit. As car makers loudly proclaimed a software-defined future, one in which their cars would become seamlessly connected to our digital lives, the immense halls of the Las Vegas Convention Centre was where they came to prove their mettle alongside the giants of home entertainment and digital devices.

And so it was that legacy automakers Mercedes-Benz, BMW, Hyundai, Kia and Volkswagen – among startups and suppliers – returned to Vegas in January ’24.

After 2023, the year in which generative AI changed everything, hopes were high. The intelligent integration of tools like ChatGPT into the products and services of the automotive realm will create untold opportunities to reimagine how we interface with cars and how they, in turn, interface with us. But on the strength of this year’s show, we’ll be waiting a little longer for cars to finally find their place within our digital ecosystems.

First out of the blocks (and the first to fail) was Volkswagen. In partnership with Cerence, they showed off a new version of IDA, their in-car digital assistant. Infused with ChatGPT – which was supposed to bring the linguistic reasoning so lacking from automotive voice control systems – IDA failed to recognise and respond to even basic commands.

More complex ones like “Hey IDA, I’ve lost my phone charger”, which depends on reasoning to deliver a list of consumer retail outlets where a replacement might be bought, instead resulted in a list of commercial electronics distributors. Did IDA read through the list? No, of course not. The driver was still required to take their eyes off the road to make a selection.

The guardrails to the large language model that Cerence had engineered were no match for the question “Which is the best car company in the world?”. Volkswagen was not among IDA’s picks. And a cute request to read the driver’s bored child a story about dinosaurs would be undone to the point of tears by the lack of cellular coverage on, say, over a third of the journey between Los Angeles and Las Vegas.

Collaborating with Will.I.Am to create an in-car DJ should be some way down the list of priorities

Under close scrutiny, BMW’s integration of Amazon’s custom generative AI model faired little better. Intended to simplify the drivers’ understanding of an increasingly complex operating environment – a noble cause – when the assistant actually understood the question, responses were irritatingly verbose and, again, entirely limited by the car’s access to a cellular network. It bears repeating that in many parts of the world, this will constitute a major point of failure and frustration.

To be clear, it’s early days for generative AI in general, to say nothing of our understanding of how it might change the way we interact with cars. But these demonstrations showed some fundamental misapprehensions about the role that these systems might play, and they stemmed from automakers asking the wrong questions.

Instead of asking what might happen when the car is constantly connected, what happens when it’s not? In a world in which a concert or, increasingly, a cyclone can take down cellular networks, how these systems fail is just as important to consider as how they succeed.

In the race to be “cool”, competence, quality, and coherence are being left behind

Instead of asking how generative AI might act as an interpreter for a complex human-machine interface, why not ask how it might radically simplify and redefine that interface and the physical architecture that contains it?

At CES we once again saw auto makers running before they can walk with the integration of these new technologies. When over-the-air updates can brick your car and software bugs can cause sudden unintended deceleration, as they did with Mercedes-Benz last year, collaborating with Will.I.Am to create an in-car DJ should be some way down the list of priorities.

And here we get to the nub of the problem: in the mad rush to try and match Tesla’s market cap, legacy car makers are throwing every new technology at their cars without really understanding how to effectively integrate them, nor – most importantly – use them to build brand equity. In the race to be “cool”, competence, quality, and coherence are being left behind.

The tech giants – Amazon, Google, Apple and Microsoft – have of course been only too happy to lend support to this endeavour. But their evident lack of understanding of what makes a car really work, let alone what makes an automotive brand unique, has flattened the role of technology to that of misjudged tinsel on the tree. Its truly transformative potential is left, as yet, unrealised.

For that, you needed to look elsewhere at the show, where a combination of audio cues and light painted on the ground restored mobility to people suffering from Parkinson’s, for example.

The Xiaomi SU7, derided by many in the Western automotive world for being stylistically derivative, attempts to answer that question, and another important one besides

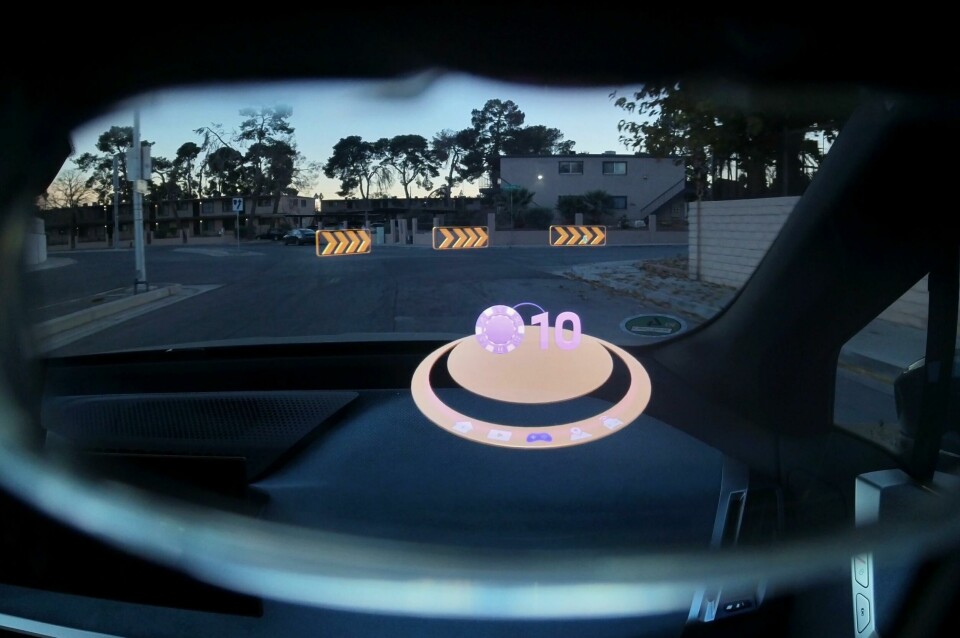

Calm technology, in the vein of technologist Amber Case, abounded, demonstrating that it is indeed possible to benefit from connected devices without being constantly reminded of their presence with glowing screens.

And companies like Rabbit and WHISPR played in ways far more imaginative and humane than the OEMs and Tier 1s with how we might interface with a world in which the app – the defining interaction archetype of the past 16 years – might soon disappear. Their products might not be the right answer, but the questions they ask are far more interesting.

But let’s return to the most interesting question of all, which is how might this fail?. Because it’s not just poorly-implemented technologies that are failing us, but the legacy OEMs who are implementing them. By confusing their essential responsibility to provide consumers with safe, reliable, sustainable and affordable transportation with a desire to be “cool”, they too are facing a failure of their own.

So how might we succeed, then? The Xiaomi SU7, derided by many in the Western automotive world for being stylistically derivative, attempts to answer that question, and another important one besides.

Rather than asking “what happens when we integrate new technology in to the car?”, the SU7 asks “what happens when we integrate the car in to a broader ecosystem, in which it is but one element?”. It’s from this position of intellectual and creative humility that radical new opportunities for automotive design emerge. It’s a position many car makers would do well to adopt.

Drew Smith is an independent design strategist at StudioPhro*, and publishes a newsletter and podcast called Looking Out