Circularity in car design requires a culture shift

Sustainable car design is finally starting to gain speed but it needs to accelerate faster and more credibly than ever. Jonathan Bell gauges the state of the industry

Towards the end of the last decade, one could get a very concrete example of the auto industry’s wayward relationship with waste. Across North America, Volkswagen was storing over 300,000 vehicles, all recalled and bought back following the ‘dieselgate’ scandal that began in late 2015. While many of these cars were subsequently rectified and re-sold, the sight of airfields stacked with rank upon rank of cars debilitated only by a few sneaky lines of computer code brought home the ‘fire and forget’ nature of mass consumption.

For the vast majority of the 20th century, production and consumption had little relationship to a product’s end of life journey. Although whole industries were devoted to servicing, repairing and ultimately breaking down and scrapping cars, it was not a closed system. Virgin raw materials flowed in, shiny new cars flowed out, beaten up wrecks staggered into scrapyards, their components and raw materials often too costly to extract and refine, with strict prohibitions against re-using old parts in new cars.

Even standard production processes had become notoriously wasteful, with pressed body panels typically creating offcuts that couldn’t be used for manufacturing. According to Renault, the European car market alone sees 11 million vehicles scrapped each year. The carmaker also estimates that around 85% of these cars are made of recyclable materials yet points out that ‘new vehicles are made up of only 20-30% of recycled material.’

Circular manufacturing is not just one giant virtuous loop, but a series of interconnecting loops, many of which are co-dependent on one another. For every miracle material that promises savings in one area, there are potential inefficiencies created elsewhere. Consider carbon fibre reinforced plastic (CFRP): it might have huge benefits for weight saving and hence energy efficiency, but according to the University of Warwick up to 40% of CFRP ends up in landfill. Using less virgin material, new, lower-carbon materials, more recycled materials and more materials that are capable of being recyclable are central spokes of the drive to circularity.

Design is one of the most important tools that manufacturers have to help signpost innovation and directions, as well as out-of-sight parts, processes and aspirations. When JLR began its shift towards an all-aluminium architecture, it made sure that the material was prominently displayed in media releases and marketing campaigns. The science was sound: according to aluminium supplier Novelis Europe, using recycled aluminium uses around 95% less energy than ‘prime’ aluminium. In 2015, the first year of Jaguar XE production, the company used 50,000 tonnes of recycled aluminium.

Battery electric vehicles have refocused attention on weight and efficiency on mass market cars. Starting with BMW’s pioneering – and expensive – use of carbon fibre in its original i3 and i8, more and more manufacturers are looking to lightweight materials, not just for structural and hidden components, but in visible A-surfaces as well. Precise figures are almost impossible to quantify, but EVs have a substantial reduction in parts compared to an internal combustion-engined car. However, fill the EV with premium technology and functions and the advantage is lost.

As part of a drive to lower-carbon supply chains, many new materials incorporate natural fibres as their structural component. Bioplastics date back to the very first plastic-bodied car, Ford’s Soybean Car of 1941, an experimental one-off allegedly made with plastic derived from soybeans and other agricultural products, albeit mixed with a formaldehyde resin. Henry Ford’s vision was clouded by a combination of over-enthusiastic PR, dangerous industrial chemicals and deliberate obfuscation as to the precise chemical make-up of the revolutionary plastic and the idea ultimately came to nothing.

In modern industry, bioplastics are increasingly widely used. BMW has hemp-based trim panels and is exploring ‘wood foam’ acoustic panels. Lexus uses the bamboo and corn-based Bio-PE for internal surfaces, as does Mercedes, while Fiat has used soya-derived polyurethanes for over a decade.

The search for prominent carbon-neutrality has also encouraged rather more marginal material developments, for example, the use of ocean plastic, which is perhaps the highest profile but lowest impact way of signalling a commitment to circularity. Ford’s new Bronco incorporates a five-gramme under-bonnet clip made from discarded deep sea fishing nets; 0.000002% of the SUV’s kerb weight. Still, it made for a few headlines and the issue of waste was nudged a few degrees more into our collective field of view.

Taken in isolation, material innovations seem like a very good thing, for they reduce the reliance on hydrocarbons and thus lower the overall carbon footprint of car manufacturing. In 2020, a McKinsey survey predicted that reduced tailpipe emissions would increase the proportion that manufacturing accounted for in a car’s overall life-cycle emissions, rising from around 18% to more than 60% in 2040.

However, given that they’re not particularly biodegradable or even recyclable, bioplastics might end up being little more than a short-term solution. This is another place where design can play a role. Unless consumers can recalibrate their expectations of how quality and newness feel, the demand for virgin materials will always outstrip the ability of materials to be used again and again and again.

For this is the true meaning of circularity, one that conventional plastics, alloys, and fibres are extremely ill-suited to. Challenger brands have one advantage, in that they can design or plan in circularity from the outset, rather than attempt to turn the tanker-like momentum of existing supply chains. On the other hand, innovation requires deep pockets and vast R&D departments.

Circular design is currently at the point where conceptual design intersects with production realities. Bold concept statements like BMW’s i Vision Circular Concept, Dacia’s Manifesto or Citroën’s Oli can all shrug off convention, safe in the knowledge that they don’t have to answer to focus groups or anxious dealers. For all their conceptual pizzazz, the i Vision, Manifesto and Oli embody elements of design and manufacturing that will simply have to change if circularity is going to make any kind of impact on the motor industry. The i Vision is the most explicit, created with the aim of exceeding ‘customers’ self-evident expectations when it comes to lifestyle and luxury,’ according to BMW’s head of design, Domagoj Dukec.

Smaller and less explicitly ‘car-like’ than one would expect from BMW’s brand values, the i Vision is pitched in the far future of 2040, giving the design team some theoretical wiggle room. The company suggests four principles for designing within ‘closed material cycles’, Re:think, Re:duce, Re:use and Re:cycle. Some elements are explicitly aligned with this approach, like the ceiling lights formed from repurposed iDrive controllers from the BMW iX. Overall, the i Vision serves to highlight the two-pronged challenge facing carmakers: how to shift perceptions as well as the supply chain.

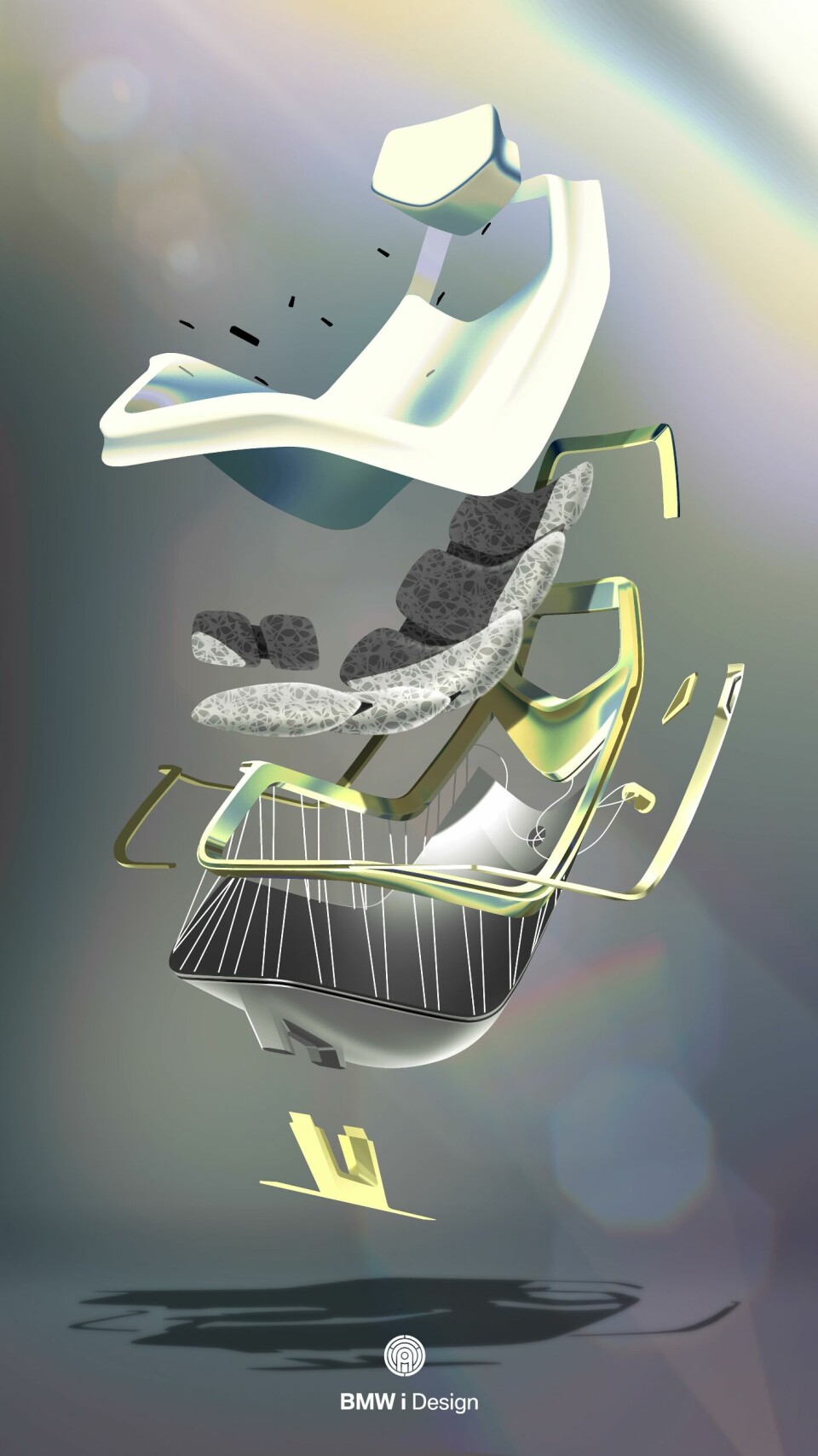

In contrast, the Citroën Oli offers a far more down-to-earth proposition, in keeping with the Stellantis-owned brand’s gradual re-positioning as a more utilitarian, practical brand. The Oli is about lightness and simplicity, with key elements of the bodywork designed to fit on both sides of the vehicle and formerly complex components taken back to the bare minimum, like the seats formed from just eight parts, rather than the 30-plus required by a conventional production car. Like its smaller sibling, the Ami, there’s nothing particularly far-fetched about the Oli, giving it a credible claim to being a true descendant of the 1948 2CV.

Dacia’s Manifesto shares a similar no-nonsense, angular aesthetic. More conceptual in approach, the Manifesto is more about ethos than achievability, although elements like the airless tyres and the company’s own ‘Starkle’ recycled plastic composite, indicate the slow but necessary shift towards physical hardiness and material imperfection that will be an inevitable by-product of circular design.

The mass premium market has a harder task. The forthcoming Fisker Ocean and Polestar 3 occupy the same growing segment: the upmarket electric family SUV. Both companies make big sustainability claims, emphasising the use of recycled materials in interior surfaces and fabrics. Any cycle of re-use is laudable, but it stops short of being genuinely circular, unless plans and systems are in place to transform redundant Oceans back into waste material.

Polestar is one of the few manufacturers to approach circular thinking with any rigour. The company’s high-profile plan is to ‘create a climate-neutral car by 2030,’ a project dubbed Polestar 0. There is some admirable forthrightness behind Polestar’s approach – the company acknowledges that it can’t draw any real conclusions until its cars have been on sale for a while, and that carbon offsetting is a last resort. The project is very much a journey, one Polestar hopes to chronicle with ‘full transparency,’ including published carbon footprint statistics for all its vehicles.

Since 2005, Renault has integrated the idea of the circular economy in its value chain, making it the first carmaker to do so. Renault Group has created a new company, The Future Is NEUTRAL, combining subsidiaries already directly involved with circularity. These include INDRA, a recycling plant capable of recovering 95% of a vehicle’s mass in materials, including parts for re-use, the scrap metal dealers Boone Comenor Metalimpex, and Gaia, a company that sets up material loops.

The company runs a ‘Refactory’ in Flins, about 25 miles north-west of Paris. The Refactory is described as ‘Europe’s first circular economy factory dedicated to mobility,’ potentially capable of re-conditioning 45,000 second-hand cars a year by next year, as well as repairing thousands of heavily damaged cars and converting commercial vehicles to electric power.

Toyota is taking another approach with its Kinto Factory, a facility dedicated to repairing and upgrading existing models, giving customers the opportunity to add driving assistants and smartphone integration to models that didn’t originally ship with them. Volkswagen is focusing on closing the various ‘production loops’ along the manufacturing process, working with suppliers to ensure that waste materials are diverted back into the supply chain, whether it’s aluminium off-cuts or battery components.

The latter can have up to 90% of their lithium, nickel, manganese, cobalt, aluminium, copper, and plastic contained within a closed recycling loop, with intact batteries reconditioned into mobile and fixed storage banks. And JLR is doing a similar thing with its Off Grid Battery Energy Storage System (ESS), developed with generator company Pramac and which uses I-Pace batteries.

By creating an economically-sustainable business model that gives cars, components, and raw materials a longer life without compromising the returns from servicing and finance, carmakers are gradually building circularity into their processes. Naturally, the dynamics of the supply chain is shifting to accommodate this focus. Whether it’s replacements for leather with vegan, synthetic or bio-derived alternatives, or surfaces and structures with textures and finishes that are more explicit about their recycled origins, there are big shifts taking place. Crucially, customers need to be on board with this radically different approach to design, surfacing, and tactile qualities.

Citroën’s marketing material for the Oli neatly summarises the challenge: “It is more environmentally and economically positive to refurbish [Oli] than replace it over several lifecycles. When no longer economical to refurbish, Citroën would turn each Oli into a recycled parts donor for others requiring parts or send other parts for general recycling.” For now, 100% circularity is still a culture shift away.