Renault Symbioz Revives a Modernist Dream

Autonomous EV the Renault Symbioz recalls an old architectural concept of integrated dwelling environments of home and transport

At the Frankfurt Motor Show, Renault had an impressive stand that included not only a concept car, but also an accompanying concept house. It was an impressive and ambitious display of near-future technology, and with its furnished lounge, a great place to hang out, too.

As our colleague Farah Alkhalisi discussed with Renault’s Stéphane Janin about the Symbioz car and house, we couldn’t help but recognise that Renault has tapped into a dream of the Modernist movement; uniting living and transport environments into one seamless whole.

It’s worth looking back at the development of these hybrid/integrated environments from both the architectural and the automotive perspectives to get a sense of perspective, as we consider the Symbioz – both house and car.

1909 ‘Robie House’ by Frank Lloyd Wright pioneered the integrated garage

Modernism – Escaping the stable

It was Frank Lloyd Wright, the elder statesman of the Modern movement, who first realized that the automobile, even in its spidery pre-1910 form, would transform life and architecture in the decades to come. Wright was passionate about automobiles and would own over eighty during his long life. He even occasionally designed cars and customized his favourites.

Wright’s early work was revolutionary in many ways, but his relationship with the car reflected the transitional nature of the times. Many cars – then toys of the wealthy – were kept in converted stables, carriage houses, or similar outbuildings. But, by 1909, Wright had a client, Frederick Robie, who shared his passionate love of automobiles, and who agreed with his vision of the forthcoming automotive age.

Robie House’s ‘motor court’ included a maintenance pit (now filled) and washing area

The Robie house in Chicago was designed to include a garage that was built into the main part of the house, not separated as an outbuilding – the first step towards uniting car and house. Later, in his revolutionary Usonian homes of the 1930s, Wright began a project which aimed to bring a modern sensibility to the average American home, and the garage was reduced to just a roof.

Wright called these minimalist car shelters “carports,” the first use of the now ubiquitous term. Wright explained in a letter to a client, “A car is not a horse and it doesn’t need a barn. Cars are built well-enough now so that they do not require elaborate shelter.”

1939 ‘Rosenbaum House’ by FLW; an early “Usonian” house with just a slab canopy, or ‘carport’, for the car to shelter under

The Swiss-French architect Charles-Édouard Jennaret, better known by his nom de plume, Le Corbusier, also saw the automobile as a revolutionary force, along with the airplane and ocean liner. These mechanical objects, of immense complexity (and, in the case of the ocean liner, size) were emblematic of the demands and opportunities of the new modern-age industrial products. They were built to exacting standards, even mass-produced when it came to the car. The house, Le Corbusier argued, should embody the same processes, using industrial means and methods to produce a revolutionary new home – which, of course, he would design (as well as a car to go with it).

Diagram of the Villa Savoye by Le Corbusier, with automobile circulation above left in yellow

This new home would, of course, have a new relationship with the car, and in his design for the Villa Savoye, he brought the car under the canopy of the house. The Villa, one of the most studied and over-analysed buildings of all time, is organized like a modern update of a Renaissance palazzo, with the main living floor, the piano nobile, raised up to the first floor (second floor in U.S. terms), with servant functions – including parking – relegated to the ground floor.

A silky seductress visits Villa Savoye. Garage is behind the curved doors

Still, one drives under and around the house to find the parking and then can step into the entry with its ramp and sculptural staircase. It is a combination of garage and porté cochere, but both are brought into the house envelope and help create an entry sequence appropriate to the machine age.

Case Study House #21, Pierre Koenig. Breakfast with your Ford just outside, like the family dog begging to come in… (photo by Julius Schulman)

The post-war Case Study Houses in California in the 1950s and ‘60s sought to distil the lessons learned from Wright, Le Corbusier and others into a new generation of homes. The program experimented with all manner of modern construction and interior arrangements, while the use of Wright’s carport idea was widespread. Several houses, such as the Bailey house (Case Study House 21) brought the car right to the front door and within view of the occupants of the home.

The Lincoln “Living Garage” project – a car is invited into the home

Living Garage or Tokonoma?

In 1958, Lincoln, along with House and Garden magazine, sponsored a project to integrate the car into a residential space, noting that the car had matured to the point where it could be considered part of the home décor.

The Living Garage, as it was called, contained a combined garage space, sunroom and playroom.

The Entertainment or play area, along with planted areas and plenty of windows, made for a casual dining and entertainment space, with the car as the conversation piece – and in the case of the Lincoln, a private lounge, as its back seat was as large as many sofas of the day.

Lincoln “Living Garage” was part sunroom, part playroom, part greenhouse

House and Garden touted the Living Garage as the next big home design trend. Alas, it never really caught on, although a homebuilder in San Diego did build some homes with “gar-ports” – garden room carports – that imitated the Living Garage idea. These were outdoor spaces, appropriate for San Diego’s mild climate. The Lincoln project was built in Connecticut, and required a winter-proof space, thus bringing the car into the house.

Holger Schubert’s Living Room/Garage in Los Angeles. The hydraulic ramp shown under the Ferrari allows the car to coast out of the house before the engine is fired up, thus eliminating fumes in the house

More recently, in Los Angeles, industrial designer Holger Schubert designed his living room to house his prize Ferrari 512 BBi. The room was a fusion of garage and living area with spectacular views of LA and the Pacific Ocean beyond. Schubert won several awards for the space before the neighbours reported him to the local authorities, who rescinded his building permit and forced changes to the home to eliminate the car from a dwelling space.

Holger Schubert’s Living Room/Garage – elegant, but doomed when he had to tear down the drive/bridge to access the house, now itself gone

For all their interesting innovations, these spaces that brought the car inside were more akin to the Japanese Tokonoma, the alcove or niche in a traditional Japanese home that displays a treasured scroll or family heirloom. The car in these “living garages” is the treasured object of desire, and the room is arranged to allow occupants to contemplate and admire the mechanical artistry, rather than augment or enhance the liveability of the overall space.

Japanese ‘Tokonoma’, an alcove for family treasures in a traditional home

A New Kind of Domestic Space?

While the car was slowly being integrated into the living space of the home, a kind of inverse process was also happening: the interior of the car was being domesticated, with home-like lounge spaces appearing in concept cars (and to a limited extent, production vehicles).

Stout Scarab- A luxury business lounge/sleeper car for the 1930s business tycoon. Often cited as the first minivan, but its aspirations were higher than a simple family hauler

In 1935, William Stout, designer of the Ford Trimotor aeroplane, decided to create an executive car, the Scarab, which would allow a business person to travel and work with ease in a rolling lounge space. Two of the seats could be repositioned or even removed from the car to allow multiple interior arrangements, including a lounge, business office and sleeping compartment.

The interior of the Ford Aurora concept station wagon

At the 1964 World’s Fair, a little-remembered concept car (overshadowed by the introduction of the Mustang) was the Ford Aurora, a station wagon with a lounge interior, designed for long journeys on the expanding interstate highway system. The front passenger bucket swivelled to face an L-shaped couch-like rear seat. An on-board TV, stereo and cooler/oven unit outfitted this rolling lounge.

Best of all, a rear-facing children’s compartment with retractable glass partition allowed the little darlings their own private space, and the parents their sanity.

NIO EVE concept updates the Stout Scarab for the 21st century. Family lounge and an office too

More recently, the Mercedes Luxury Vision 015, and NIO’s EVE concept car expand and update the lounge theme for the coming autonomous age. The Mercedes is a four-passenger lounge, with front seats that can swivel to face the rear passengers. The NIO is also a four-passenger lounge, but with two additional seats up front for occasional driving. The NIO interior can convert to an office, or, with its reclining chair, can be a sleeping compartment, much like the Stout Scarab.

Both cars reflect the current and near-future developments in electric power, autonomy, and artificial intelligence. They are a bit like a rolling “smart home” or office, updating some of the earlier concepts like Aurora or Scarab to anticipate tomorrow’s living and travel environments.

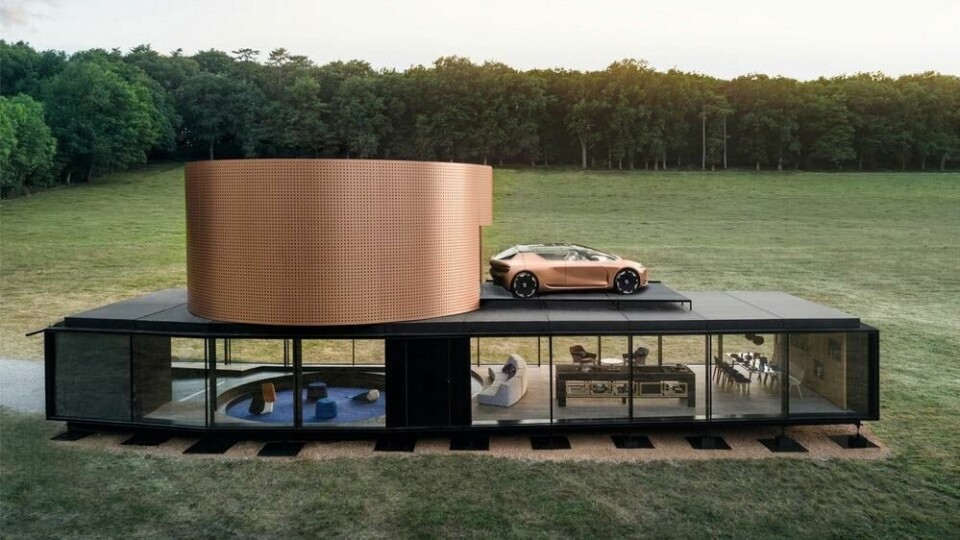

Symbioz concept car and house, one an extension of the other

Bringing it all together

This brings us back around to the Renault Symbioz. It has the lounge characteristics of the cars mentioned above, but strongly interacts with its home “base”. The ‘smart home’ extends itself with the Symbioz car, out into the landscape.

While at home, the car acts as an extra room and a mobile penthouse, extending on a platform over the room.

The Symbioz is electrically powered, thus allowing to it to occupy a position in the home that an internal combustion car never could. Interestingly, Holger Schubert, of Ferrari-in-the-living-room fame, foresaw this day. He also owned an electric car and predicted a day when the car could be driven inside and docked, unloaded and connected to internal home systems. The Symbioz carries that concept to the next level with advanced connectivity, electric power and AI systems.

The Symbioz car admires the view in penthouse mode

A few years ago, architect Rafael Moneo, noted:

Architecture must also assume its role in assimilating and integrating the automobile, finding a place for it in its agenda. I don’t think anyone would be surprised if I were to say that architecture has so far made very little effort to try to coexist with the automobile…

The Renault Symbioz gives us a tantalizing glimpse of the future not only of architecture/transport coexistence, but integration. It is one in which your smart environment is with you wherever you go - rising with you in the morning, travelling with you as you go about your day, and then welcoming you home to rest and recharge in the evening.

Just be sure to wipe your wheels before you come in…