What has happened to Audi design?

(Single)Framing the rise and decline of design kings, Audi. Design critic Wayne Batty is unconvinced by the Bauhaus aspirations of the German marque’s ’Sphere series

In the context of global pandemics and unprovoked invasions, crimes of style are of little importance. That doesn’t mean they’re not happening. Elantra, Cybertruck, [BMW] XM, please stand up. The latest release to get my keyboard furiously clacking, though for vastly different reasons, is what Audi calls: urbansphere. Basically, it’s a battery-powered, level 4 autonomous, private jet fuselage-shaped four-seater designed to navigate a Chinese megacity. It’s the third concept in the company’s ’sphere series and is by far the largest. In fact, at 5.5 metres long, almost 1.8m high and more than 2 m wide, it’s the largest Audi ever conceived. The company’s marketers call these proportions ‘stately’ – they’re not wrong. If it doesn’t appear all that large to you, please note, these are 24-inch rims.

Electric vehicles without range woes demand massive real estate. That most car makers appear oblivious to the sheer hulking bulk of their ‘planet-saving’ electric vehicle offerings is pure irony gold. But that’s not my chief gripe with the urbanspere. Principally, I’m piqued at the release material’s use of phrases such as ‘traditional Audi shapes and elements’ and ‘the Bauhaus tradition of the brand’s design’. Put simply, there is nothing traditional or Bauhaus about urbansphere.

As for ‘Bauhaus tradition’: if ornament is crime, then there is a lengthy strip of brightwork that deserves to do time

Let’s begin with the reinterpretation of the singleframe ‘grille’, an Auto Union-referencing item that surfaced in 2004 and, courtesy of Audi’s (and others’) current penchant for exaggerated styling, has grown in both size and edge count ever since. The question is: does urbansphere even need the singleframe? Without an engine to cool, radiator grilles serve no function. Teslas don’t have them. Legacy makers seem incapable of ditching them, rather tending to retain them as decorative graphics. In the urbansphere, thanks to the loss of vertical metal elements, the not very ‘traditional’ singleframe element now bleeds across the full width of the nose – so large it could swallow an A1 whole. You see Audi? It’s easy to play the exaggeration game with a little too much enthusiasm.

As for ‘Bauhaus tradition’: If ornament is crime, then there’s a lengthy strip of brightwork that deserves to do time. It runs from a point somewhere between the base of the two front-most roof pillars, in an arc that splits the side glazing and sweeps around into the rear roof extension lip – a purposeless feature that also restricts outward vision. Sorry Audi, pointless decoration is not a Bauhaus tenet.

Just how did we get here, and why do I care so much?

As a kid growing up in the 1980s, performance stats were all the rage, but I was far more enamoured with how cars looked. Exotics aside, one brand was working hardest to garner more of my admiration – Audi.

It began with the 1982 Audi 100, a car whose NSU Ro 80-hat-tpping body was as sleek as its marketing was slick. If ever a single car was responsible for taking drag coefficients mainstream, it was the 100. Overnight, Cd values started vying for their own Top Trumps category. All the while, Audi was shaking its ‘fancy Volkswagen’ tag by pushing a message of technology.

They didn’t invent it, but when Audi launched the quattro coupe in Geneva, they certainly took ownership of four-wheel drive. Watching a 136bhp Audi 100CS quattro drive up a 38-degree ski jump sure hit home.

The brand would also become inextricably linked with five-cylinder engines, fully galvanised bodies and TDI turbo diesels. And it was Audi who pioneered the use of all-aluminium bodies for production series cars, dazzling 1993 Frankfurt show goers with the ASF concept’s highly polished panels.

With unquestionable technological prowess in the bag, Audi turned the spotlight to design, blazing a trail that few could match.

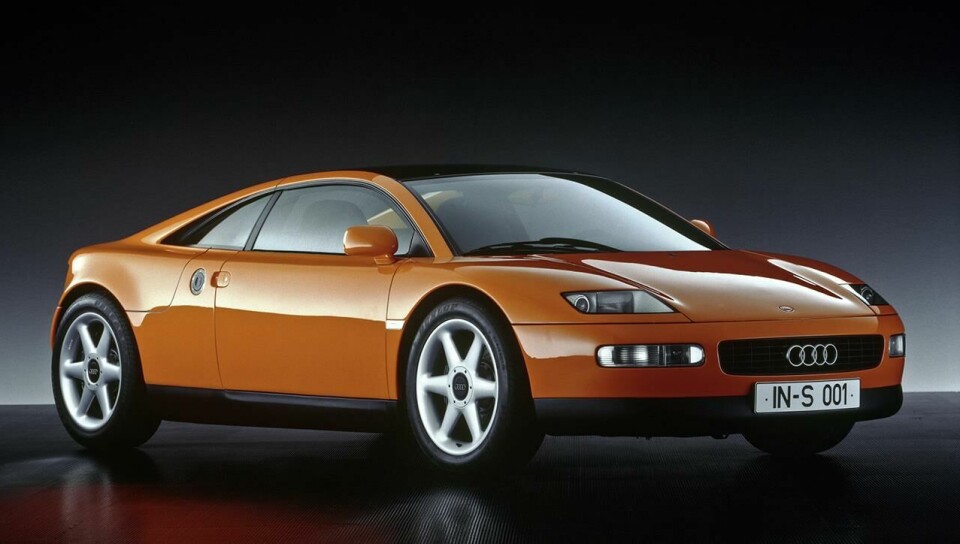

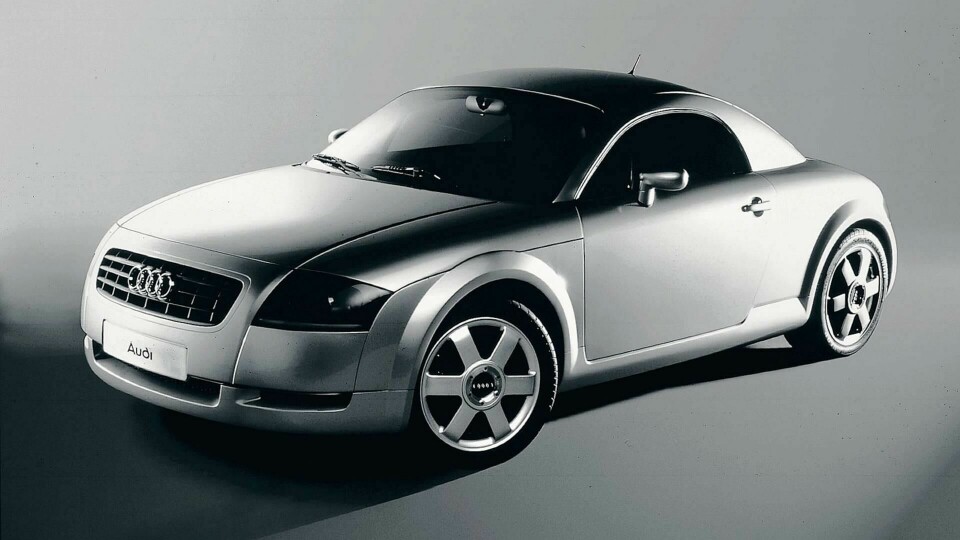

Unforgettable early-1990s concept cars – quattro Spyder and Avus quattro – burned permanent sectors on my brain’s hard drive. But it was the 1995 TT concept that really lit Audi’s design fuse. With undecorated surfacing and pragmatic Germanic solidity in perfect balance with disciplined proportions and visual line purity, it was the ultimate automotive avatar for Bauhaus.

Then, in 2000, the Rosemeyer concept arrived as a rolling vented vault, a romantic Auto Union-fuelled dalliance whose only purpose was to herald the introduction of the singleframe grille across the production car range. A bold move that perfectly expressed hard-earned confidence and underscored the notion that Audi had well and truly taken the design high ground. The cars from Ingolstadt were the envy of every design studio from Detroit to Tokyo.

I remember standing alongside an all-new A6 at the 2018 Geneva Motor Show totting up the horizontal lines littering the side panels before gasping at the sight of the reverse crease on top of an already well-defined blistered wheel arch

It is around this time that Walter de Silva arrived – via a three year stint at SEAT – from a masterful tenure at Alfa Romeo. As the one holding the reins, he is to blame for complicating the traditional Audi language. Blame? Many will point to the ‘beautiful’ 2007 A5 coupe and say he is to be applauded instead. I say look at the 2003 Nuvolari concept and ask yourself what went wrong.

Let me be clear, de Silva is an outstanding designer who is to be revered, one who deserves his place among the car design greats, but what he brought to Audi was emotion. His wavy tornado line brought disruption to the stoic order of Bauhaus tradition. The age-old doors of restraint were busted wide open. Unnecessary lines, decorative elements, sharper and angrier shapes and exaggerated styling features began to appear, very slowly at first, but with ever greater intensity as the model years rolled by.

I remember standing alongside an all-new A6 at the 2018 Geneva Motor Show totting up the horizontal lines littering the side panels before gasping at the sight of the reverse crease on top of an already well-defined blistered wheel arch.

Back to the urbansphere and its colossal transparent singleframe. Edge count now measures a minimum of eight and its entire purpose is to define an area of swarming LED lights referred to as the Audi Light Canvas. The opportunities this system affords in terms of myriad dynamic lighting effects is all quite impressive, and on a scale that can be seen from space – probably. But mostly, it’s unnecessary, dubiously decorative and has, definitively, nothing to with traditional Bauhaus principles.