Hitting the e-SUV spot

OEMs are rushing to bring out more electric SUVs in a bid to meet emissions targets and protect margins. But they will require innovations in design and engineering to stay desirable and competitive in an increasingly crowded field

The relentless trend towards SUVs is apparent across virtually all vehicle markets. SUVs, including crossovers and compacts, are now the most popular vehicle segment in Europe, reaching 40% of sales. In North America, the SUV segments are more than 45% of sales, and together with pickup trucks account for around 70% of the light vehicle market; at current rates, they could approach 80% by the middle of the decade.

Carmakers continue to launch new SUV and compact SUV models even as they pare back sedan offerings. In North America, Volkswagen has not only recently added the Atlas and Atlas Cross Sport to its line up but is now launching the new Taos compact SUV. In a telling symbolism, it began production of the model this past October in Puebla, Mexico, where it took over assembly space that until last year produced the iconic (but less profitable) Beetle.

The popularity of SUVs over smaller vehicles, which has accelerated even during the Covid-19 crisis despite their higher price tags, is in stark contrast to the aims of emissions regulators and environmentalists. SUVs are invariably bigger, heavier and less aerodynamic than traditional sedans, with considerably worse fuel consumption and higher CO2 emissions.

This shift in model mix is the main reason why, despite technical advances, average EU vehicle emissions for new cars actually rose slightly in 2019 ahead of tighter flee emissions coming into effect from this year, and why SUV-heavy OEMs such as Jaguar Land Rover are facing high fines. And it certainly demonstrates the challenges that OEMs in North America face in improving fuel efficiency and reducing emissions.

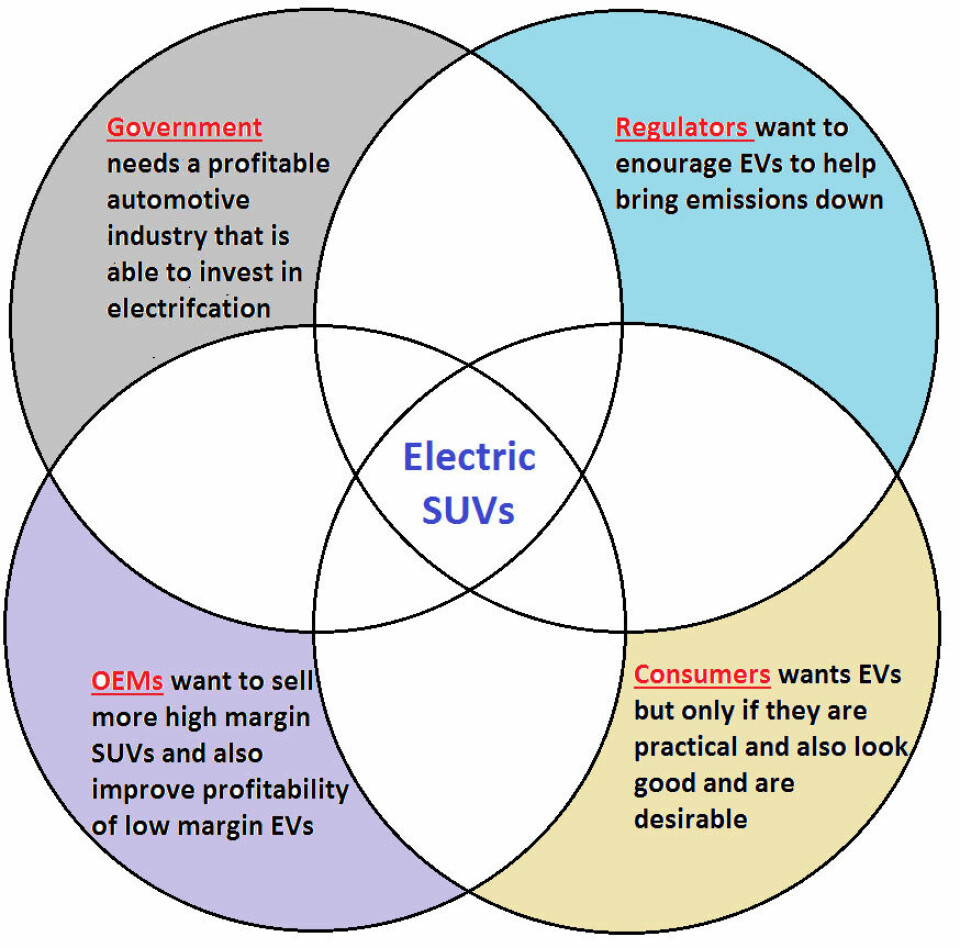

Enter the potential savour: the electric SUV. Vehicles that have the potential to meet consumer preferences and reduce emissions.

By our estimate, there are more than 40 electric SUVs currently or shortly appearing on the market in the US and EU, with many more derivatives to follow. China will likely see this many model offerings in its domestic market alone.

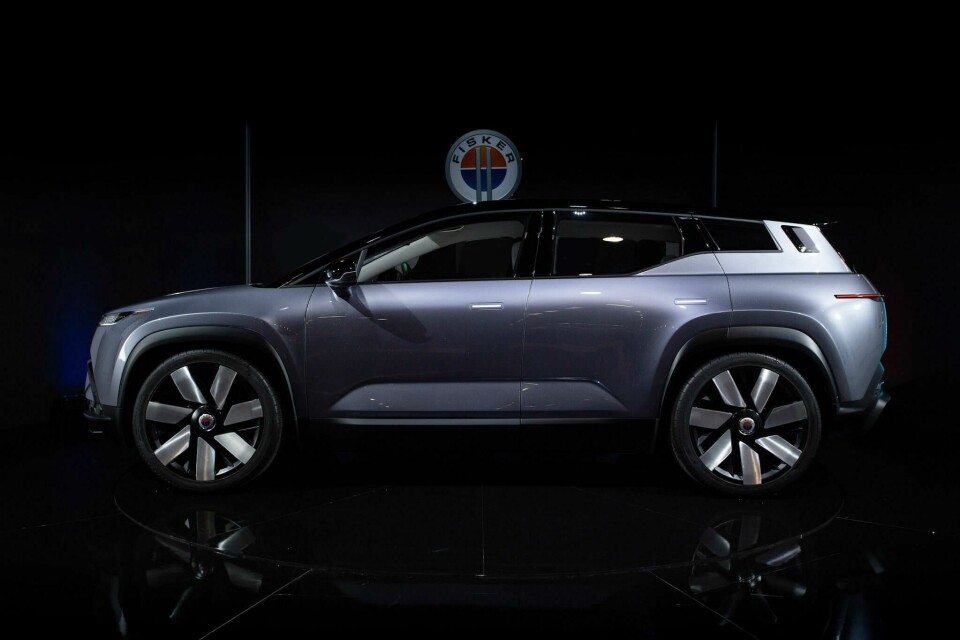

OEMs are starting to target more middle and crossover segments of the electric SUV market, such as the Peugeot e-2008, Nissan Ariya, Cupra El-Born, Volvo XC40 Recharge, Volkswagen ID.4 and Skoda Enyaq iV. However, where OEMs have really been pushing is in the luxury segment, including the Audi e-tron, the Tesla Model X, Jaguar I-Pace, Mustang Mach-E, Mercedes EQC and Porsche Taycan, and forthcoming models like the electric Porsche Macan, BMW iNext and Cadillac Lyriq. It is also higher cost models in which startups and new players are looking to make their mark, such as the Polestar 2, Nio ES range, Xpeng G3 and forthcoming Rivian R1s and Fisker Ocean.

In North America, carmakers are also pinning their hopes on electric pick-ups. Over the next two years, Ford will launch an electric F-150, Tesla the Cybertruck, Rivian the R1T along with offerings from startups including Nikola, Lordstown and Bollinger. Even the vehicle that once seemed to epitomise a disregard for environmental concern, the Hummer, is returning as an electric vehicle. GM has just unveiled the new version – expected to launch in September 2021 with a six-figure price tag – which the carmaker now considers to be a halo for its entire electric vehicle range over the coming years.

What electric dreams are made of

The profit motive here is obvious. SUVs and pick-ups have long made good business sense for carmakers. While the models cost slightly more to manufacture, they have a higher perceived value and image. Consumers are willing to pay more for the prestige, commanding driving position, extra cabin space, versatility as well as a perception of better crash protection.

In the US, there is the added dimension of long-standing tariffs on pick-ups made outside North America (the ‘chicken tax’), which has contributed to turning the market for otherwise utilitarian vehicles towards the luxury end of the market.

The profitability of SUVs has made them even more important to OEMs in the face of declining margins and higher cost pressures in recent years. And with global vehicle sales set to decline by 20% year-on-year in 2020 according to our global demand forecast 2020-2030, every profitable sale matters more than ever.

That is perhaps especially so as sales swing towards electrified vehicles in more markets. In Europe, for example, electric and plug-in hybrid vehicle sales have risen by more than 40% in the first nine months of this year compared to the same period in 2019, even as overall sales volumes declined by around 30%. These vehicles are a clear growth segment – but in many cases OEMs would be selling electrified vehicles at a loss without government subsidies or purchase incentives. EVs are currently more expensive to manufacture than ICE vehicles, but OEMs must increase EV sales to meet increasingly tightening emissions regulations particularly in the EU and China. This requires heavy investment in developing electric vehicles and batteries.

That is partly why, in a remarkably short period, OEMs have shifted to selling more electric SUVs. In July this year, for example, some 48% of electric vehicle sales in Europe were SUVs.

Electric SUVs go some way towards resolving environmental, energy, image and margin issues. An electric SUV might have a slightly shorter driving range (or require a slightly larger battery) to counteract its relatively inefficient aerodynamics, however in most cases it will still cost users 20% of the cost of filling up an ICE while producing zero tailpipe emissions. And while electric vehicles had until recently struggled with an image of being slow and unsexy, the latest electric SUVs and pickups stand a better chance at meeting both regulator and consumer desires – and at a margin that OEMs can live with.

Figure 1: Electric SUVs at the crossroads

SUVs distinguished by design

Much like those powered by internal combustion engines, the electric SUV provides carmakers opportunities to improve margins compared to other models that share the same underpinnings. For example, most buyers would consider the 2020 Peugeot e-2008 compact SUV and the e-208 sedan as two different models. But as is increasingly the case across OEM group model ranges, they share many of the same components and architecture. They are both built on PSA’s e-CMP platform (also used across other PSA Group EVs including the DS3 Crossback e-Tense and the Opel/Vauxhall Corsa-e). Both vehicles have the same 50kwH battery pack, powertrain and electronics. A closer look will reveal that they even share the same cabin and many interior features.

The e-2008 is essentially the e-208 with a slightly jacked up and higher body. The cost to develop each vehicle would be largely the same spread across the PSA Group, while manufacturing and material costs for the e-2008 would only be marginally higher. But the e-2008, at comparable trim levels, retails for around €3,500-€5,500 ($4,200-$6,550) more than the e-208. And that ability to be able to charge a higher price is critical when average industry margins were (pre Covid-crisis at least), typically only around 6%.

This common architecture comes with compromises, however. Many would argue that the e-2008 is not a ‘true’ SUV, and they would not be off the mark. It’s only 2-wheel drive, while its road-going tyres and suspension are not intended to go off-road. The e-2008 features slightly larger tyres as the sedan version, but they are the same Michelin standard tyres. Just slighter longer and wider than the e-208, it is the e-2008’s packaging and 10cm higher cabin that mainly helps it look like an SUV. But it is an appearance of considerable value to consumers.

By the nature of their size, weight and shape, however, electric SUVs and pickups present challenges in design, engineering and manufacturing. But they are also forcing innovation and opening up new possibilities for OEMs.

For example, SUVs have already challenged designers with their aerodynamics and with adding distinct styling to bulky bodies. For electric vehicles, aerodynamics is important in improving battery range, with the added size of an SUV requiring even more consideration. Furthermore, electric vehicles are often 200kg-300kg heavier than ICE vehicles because of their batteries. Electric SUVs can overcome some of these technical challenges with technology such as regenerative braking, which recoups the power consumed during acceleration when decelerating and reduces the significance of weight. OEMs also often fit low rolling resistance tyres, which can increase range by 10-20%. However, designers and engineers are constantly looking at innovative ways of reducing drag, including hidden door handles and electronic wing mirrors, as well as new ways of managing airflow and heat exchange without the need for a front grille.

The SUV design also has another key advantage which makes it more suited for EVs: the typical 10cm-15cm extra height of an SUV allows the ideal positioning for a large, high capacity battery pack to be placed on the ‘skateboard’ platform without unduly encroaching on the cabin space.

Material use and manufacturing are also in focus as OEMs ramp up more electric SUVs. For years, OEMs have sought to apply lightweight advanced materials such as carbon fibre composites, aluminium and titanium to bring down weight and thus improve fuel efficiency. However, these materials are often more expensive than steel and eat into tight profit margins. Improvements in regenerative braking reduce the significance of weight. Furthermore, EVs do not have to meet emissions targets (as their emissions are counted as zero). To that extent, regenerative braking downplays the significance of lightweight materials for heavy SUVs and could help reduce manufacturing costs further.

Peugeot’s e-2008 is again an interesting case study in crossover SUV design. Despite its extra 10cm height and worse aerodynamics, the vehicle’s range is only reduced 5% compared to the e-208, from 217 miles (347km) for the sedan to 206 miles for the e-2008 according WLTP standards. This not only vindicates PSA’s decision to fit the same 50KwH battery, and standad tyres (in contrast to the low rolling resistance tyres found on EVs such as the VW ID.3 and BMW i3) but it also demonstrates how the ‘aerodynamic premium’ of an SUV is often overstated and becomes even less important when it comes to EVs.

Charging ahead in a crowded field

Many OEMs are virtually tripping over themselves to bring more SUV variants to the market. But success and profitability are not guaranteed. Firstly, these models compete with traditional SUVs for which technology has also improved and purchase costs may be lower. And even though carmakers are electrifying their range, many continue to invigorate highly ICE-based SUVs, such as new versions of the Ford Bronco, Jeep Wagoneer and 4-door Wrangler, the Land Rover Defender and upstarts such as the INEOS Grenadier.

As the electric SUV segment becomes more crowded, many models are unlikely to succeed. But that doesn’t mean the pie won’t be big enough for most OEMs to grab a decent slice of the pie.

The electric vehicle looks likely to have a big future – it’s just becoming clearer that OEMs and consumers also want bigger electric vehicles.