“A car designer’s dream” – looking back on VW’s Potsdam studio

Car Design News spoke to design bosses past and present plus other notable alumni to find out what Potsdam was like in the glory days – plus the possible reasons behind its closure. Peter Wouda, Thomas Ingenlath, Stefan Sielaff and more offer honest reflections, fond memories and surprising revelations

Studio closures are rare occurrences these days, so it came as a shock to hear that Volkswagen’s Potsdam design centre would shutter by the end of 2024.

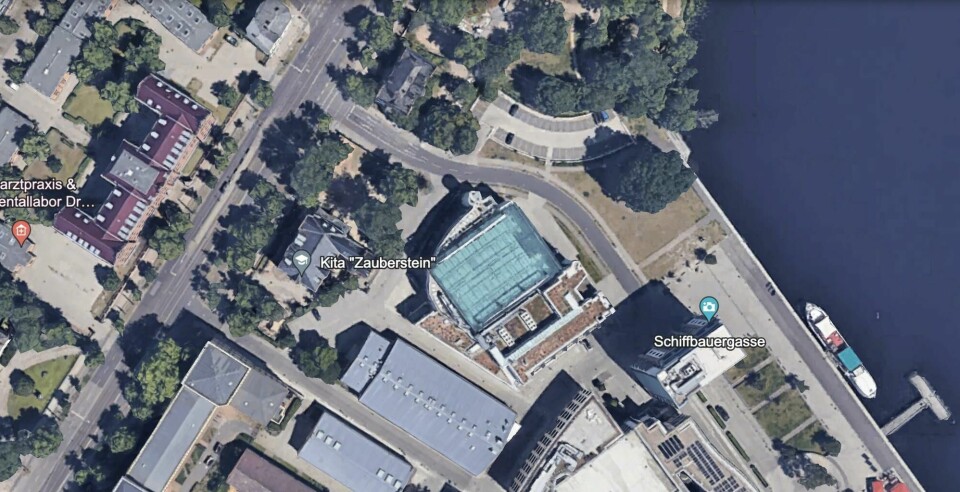

Borne from a desire to bring the best creative talent close to home, and to stretch the boundaries of design, the stunning waterfront structure tore up the rulebook when it came to what a studio should look like. Some of the biggest names in the industry came through these doors, and it has been responsible for some of the most progressive and future-looking cars the industry has ever seen.

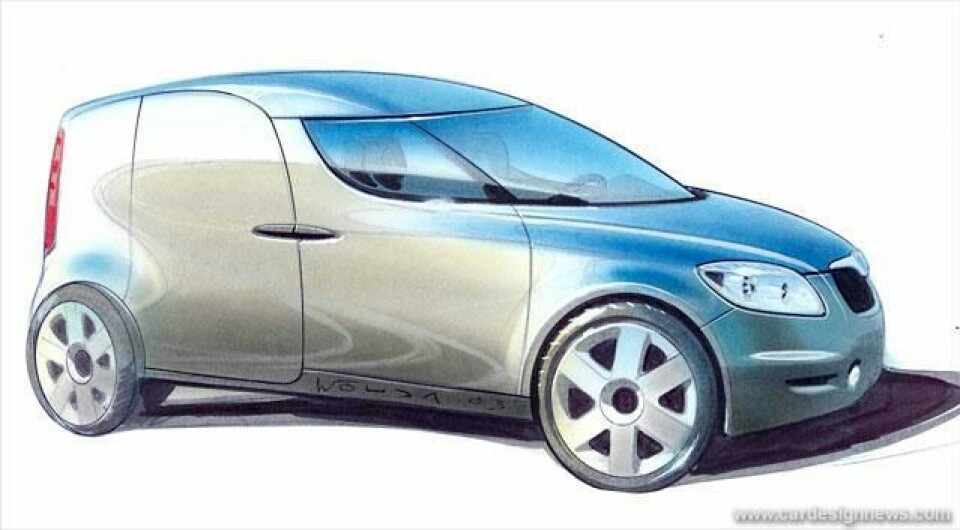

Here, teams were essentially given free rein to work across the umbrella of brands, from Audi and Bentley to Cupra, Lamborghini and Skoda – even MAN Truck & Bus. Iconic Bugatti models started life here, as did the gamechanging Volkswagen XL1 and 2009 Volkswagen Concept BlueSport, a TT-esque prototype put together by Klaus Zyciora (then Bischoff), Thomas Ingenlath, Peter Wouda and Romulus Rost.

Indeed, the site played a formative role in the careers of many big names in car design: Walter de Silva, Luc Donckerwolke, Stefan Sielaff, Tobias Sühlmann, Pontus Fontaeus, Maximilian Missoni, Anders Warming. The list goes on: Marc Lichte, Jozef Kaban, Robin Page, Jorge Diez, Sasha Selipanov. You get the idea. Potsdam has been nothing less than a production line of design Galacticos.

Selipanov joined in 2005 and says that he owes much of his current skills and design thinking to Potsdam. He came through the ranks with other fresh-faced designers including the likes of JP Gregory, Tobias Sühlmann and Daniel Scharfschwerdt, exterior designer of the Potsdam-led Up! Lite concept and currently creative manager for exterior design at VW.

To the many that worked here over the years, the pending closure hits deep. “I was not surprised, but I’m nevertheless very saddened by this news,” Selipanov told Car Design News. “It was a place of utmost significance for me and many of my friends and ex colleagues.”

Prime location

Part of the attraction was its proximity to Berlin, which in the early noughties was considered the place to be for ambitious creatives in Europe. In many ways it was conceived as a copy-and-paste of the Sitges studio in Barcelona, which was originally installed for the same reason: to attract the best young talent.

The problem was that Sitges was deemed a little too detached from the Wolfsburg mothership, and so Potsdam – about 20 miles from the centre of Berlin – emerged as a solution. Designers recall fond memories of zipping up and down the Autobahn between Berlin and Wolfsburg for meetings, and in the case of senior directors, enjoying the benefits of a brand with access to some of the more luxurious marques such as Porsche.

“Outside of an amazing work culture, brand portfolio and top-notch talent, we were all attracted to one of the cultural capitals of the world,” Selipanov says. “Berlin in the early 2000s was just incredible.”

Between 2012-2015 it was Stefan Sielaff who served as design director, taking over from Thomas Ingenlath who had left to lead Volvo design. Sielaff fondly describes the role as a “double assignment” given his existing job handling global interior design for the VW Group. He too found its location alluring: “The film studios of Babelsberg were nearby, and you could feel the creative stimulus in this historic environment at the border of Berlin. We entertained many board meetings and presentations over there.”

Seen through glass

Ingenlath had joined much earlier in 2006 at the behest of Murat Günak, who gently advised that his time at Skoda was up and a new, exciting promotion at Potsdam awaited. The current CEO of Polestar recalls being a little dumbstruck by the building, a very modern structure that appeared to be 50% glass, not at all what you’d expect at the time.

The intent was to use the shelter of nearby trees and the Tiefer See lake as protection from prying eyes, allowing for a very open, airy environment unfamiliar to most designers where a studio was a place of intense secrecy. This was of course met by delight by the vast majority of those who worked there. “The building was amazing and the location at the shore of the lake very impressive. A different world,” recalls Sielaff.

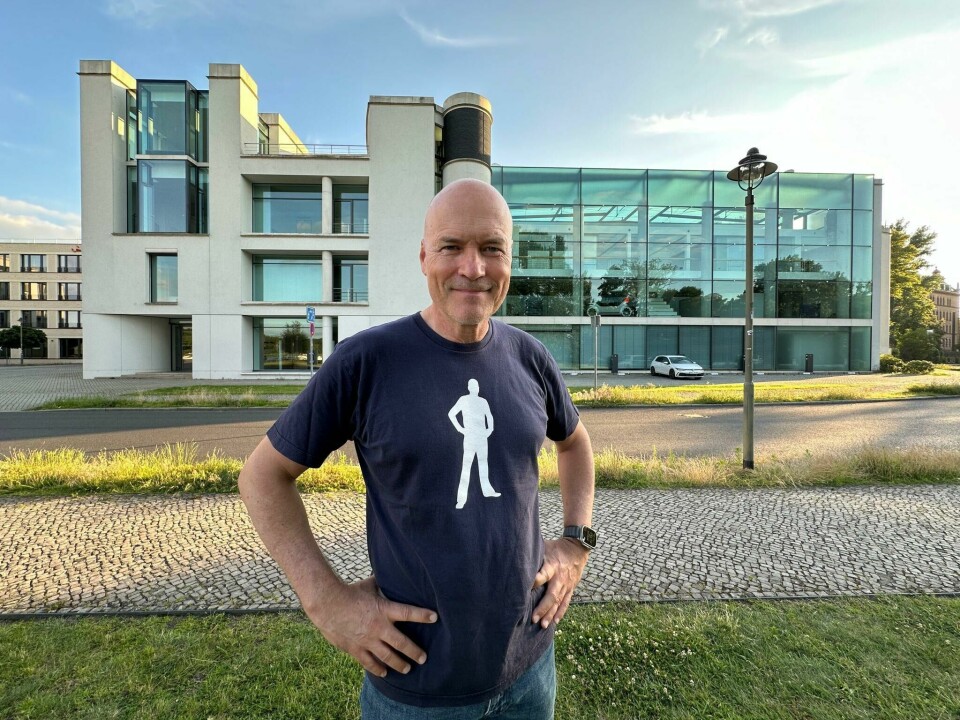

“It has huge windows, so you get tons of daylight. Even the ceiling is glass,” adds Peter Wouda, the studio’s most recent boss. “It’s a dream building for car design work. There’s so much daylight that it feels like you’re outside.” The signifiance of this should not be overstated. Car design studios are not often known for their transparency – in both senses of the word. For example, the Geely design campus in Gothenburg was built with a (hugely expensive?) glass atrium hidden within the heart of the building, welcoming natural light but preventing prying eyes. Potsdam almost seems to dare onlookers to have a peek.

Beyond the daily dose of vitamin D, this layout promoted a laid-back atmosphere where chance encounters might lead to more than just weekend plans. It encouraged teamwork without openly stating that. “Because the whole building is so transparent [at Potsdam], you can almost see everybody inside,” continues Wouda. “You don’t have many walls or doors, you can walk around and wave at eachother and meet your colleagues at coffee machines which are spread over the place. It’s an architecture which fosters transparency and collaboration.”

At some point, it dawned on senior management that perhaps beauty had trumped practicality and, for all its natural sheltering, the risk of secret projects being leaked was deemed too great. Metal ‘wings’ were installed along the ground floor which, in Ingenlath’s eyes, spoiled the whole indoor-outdoor feel during design reviews. “This kind of exhibition hall just didn’t work,” he told CDN. ”It’s mind-blowing to me how that [original design] was approved.”

Ironically, one of the few leaks that did come originated from an internal staging blunder and not from paparrazi. During an official photoshoot that had been carefully prepped to hide certain projects, the reflective floor tiles accidentally showed a car – thought to be hidden away – that was deep in development.

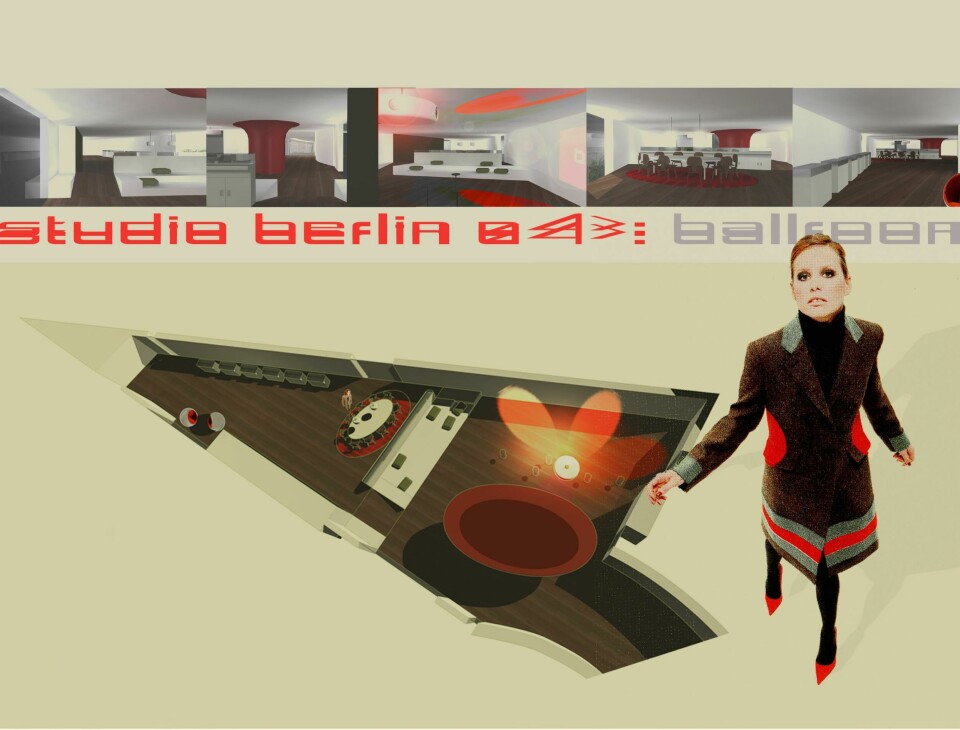

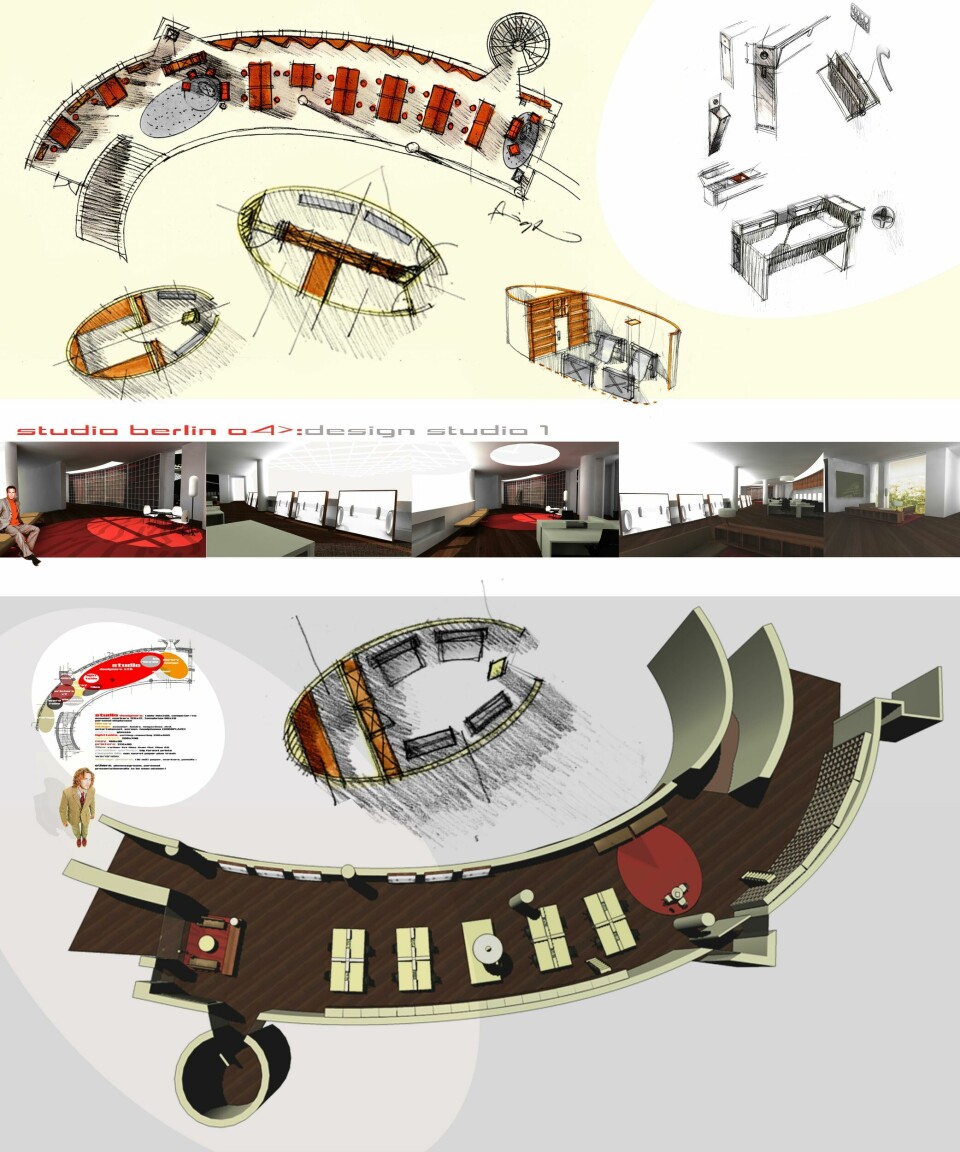

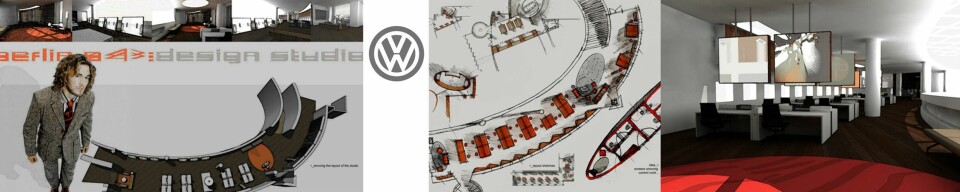

Although an architecture firm was of course involved, it was Pontus Fontaeus who put his hand up to propose some designs for the building and its internals. Between 2001 and 2004, he led the team that collaborated with the agency and directed the general interior layout. Speaking to CDN from his current studio at GAC Advanced Design Los Angeles, he recalled how the team had tried to steer executives away from something that looked like a “boutique hotel.”

In the early stages there was an exploration of different spots in Berlin – places that were “a little more hip” in Fontaeus’ words – and the initial intention for quite an unassuming building also went out of the window. “The more we were drawing and the more functions we added, it just grew and grew,” he recalls. “Instead of being a little villa with a lot of land around it, it ended going almost to the borders of the properties around it.”

As is often the case in the design world, something else came up and Fontaeus never actually worked in the place he helped to design – instead joining Hyundai-Kia in Frankfurt. Some of his early proposals for the Potsdam studio can be seen below.

All things considered, it must have been a blast to work at Potsdam. Given the wealth of brands in the group, the range of projects on the table was incredibly diverse: teams may have worked on a barebones mass-market city car before moving on to an ultra-luxury sedan or hypercar.

“In my case, both the Lamborghini Huracan exterior and the Bugatti Chiron exterior began their life as Potsdam advanced design projects and led to my joining the respective teams at Lamborghini and Bugatti,” says Selipanov. “Those projects opened many doors for my future career.”

Group perception

However, accounts from those that worked there suggest that not all Volkswagen Group employees looked fondly at Potsdam; here was a group of maverick designers essentially doing what they wanted in an idyllic lake-side venue, while the production teams were working to the strictest of parameters in a more primitive setting.

“I came from a very simple design studio at Skoda, which didn’t have any of the fanciness and luxury that was waiting in Potsdam. It was a very harsh contrast,” recalls Ingenlath. ”I can see how it might have had a problem as far as its image in the group.”

And for all the freedom afforded across the multitude of VW Group brands, some designers have reported feeling a lack of connection that comes from being embedded at a certain brand. “It’s a life that is very rare in the car industry,” says Ingenlath. “I’ve otherwise always been connected to a brand; I missed that towards the end and was happy to leave and be with one brand again.”

As its name might suggest, the Future Centre was created to play something of a different role to other studios in the Group’s design footprint. In recent years, the focus had been on autonomous driving with concepts like SEDRIC and the Tropfenwagen-inspired Gen.Travel. Work had become more research focussed, exceptionally future-looking and less of a conveyor-belt for designs destined for the factory and major motorshows.

From our conversations, you get the sense that the early days of Potsdam were indeed the glory days, the golden age. Money seemed to be no issue, management had faith in its standing and the idea of “future mobility” was beginning to challenge accepted notions of car design. It played an incredibly useful role and the group was happy to stomach the cost of running such an outpost.

Its pending closure, then, is perhaps a reflection of the current state of play where budgets are tightening and in-house design teams are more capable and multi-faceted than ever. Let us not forget either that the Volkswagen Group is still paying the price – literally – for the Dieselgate scandal. Potsdam may simply have become an expensive luxury.

”I think it was an expression of what design meant during the height of the Piëch era, how management was willing to invest into product creation and when design became a driving force for economic success,” suggests Ingenlath. “They wanted a place for the best desigers to shine and [Potsdam] was definitely a manifest of this. The level of quality, the diversity of people… It was an incredible level of professionalism where you did everything to get the best design possible out there, whatever it costs. But of course, there is always a cost.”

With Potsdam closing, this leaves two other VW Group Future Centres: one in Belmont, California and another in Beijing. The US studio will focus more on digital user experience while one in China is more market-specific; both have significantly smaller design teams and have been described as research outposts. The official statement is suitably vague, suggesting that Potsdam’s work has been largely absorbed by the design operations of each individual brand in the Group.

Whatever the rationale, the decision to dissolve Potsdam feels like a sombre moment. While there is no shortage of design studios around the world, few others have attracted and retained so many talented designers over the years; an informal school of design that brought big names through the ranks and accelerated them to successful careers both within and beyond the VW Group.

Athough it is a sad moment – and a decision that the local trade union is fighting – not everything is meant to last forever. The site ran with extreme success for much of its two-decade tenure and should be applauded for its contribution to the design world, if not a catalyst in reshaping the way design is approached across the industry. Former director Stefan Sielaff offers some words of wisdom for those possibly left in the lurch: “Times are changing and change is the salt of life. An end is also a new start.”